June 1–November 24, 2013

Loosely defined, an encyclopedia is a systematic survey of specific topics. As objective as it might strive to be, such a survey inevitably involves both sides of the epistemic equation: the world—which may or may not resist, or be exhausted by, the categories imposed on it—and the knowing subject—its ambition, or dream, or illusion, of being able to come up with a meaningful set of such categories and actually impose them. The international exhibition at the center of the 55th Venice Biennale, Massimiliano Gioni’s “Il Palazzo Enciclopedico,” is as much about the former as it is about the latter.

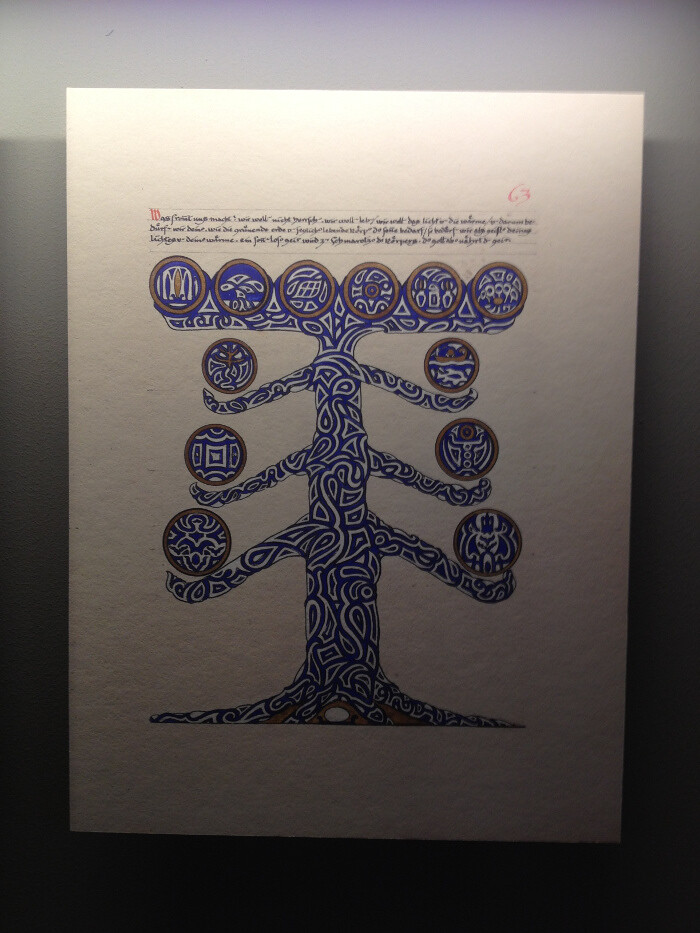

It is, in fact, two shows, or rather two variations on a theme. The one at the former Italian Pavilion in the Giardini has a circular structure, both beginning and ending with Carl Gustav Jung’s darkly exuberant Red Book (1914–1930): hundreds of hallucinatory, miniature-like images that the psychoanalyst drew over the span of sixteen years—a rhapsodic mapping of the symbolic unconscious. Here Gioni’s exhibition focuses on the encyclopedia as an idiosyncratic struggle—the impossible, yet nonetheless deeply human attempt at knowing the structures of the world. The part of the exhibition taking place in the Arsenale is linear and suggests a possible evolution of the way this structure has been imagined. It opens with the Palazzo Enciclopedico, a utopian architectural model for a museum of all human knowledge, patented in 1955 by Marino Auriti, a retired car mechanic. It closes with a sequence of chaotic and overcrowded video works (most notably Stan VanDerBeek’s immersive 1968 Movie Mural), offering a stark rendition of how such encyclopedias have been approximated by the Internet.

The exhibitions, however, share both a general theme and curatorial focus. Which is on, well, encyclopedias: archives, libraries, or collections-cum-installations in which the systematic repetition of a gesture (taking a photo, drawing something, picking it up from the ground) reveals the aim or the fantasy of exhausting its possibilities. Their most typical form is that of the collection. One of the Giardini’s most delicate rooms, for instance, displayed French Surrealist Roger Caillois’s collection of over a hundred rare geodes—their flamboyantly colored geometrical patterns and crystalline structures arranged in progressions, suggesting both a museum of natural history and the visionary maps of an alien landscape. Similarly, the Arsenale showcased Italian artist Linda Fregni Nagler’s The Hidden Mother (2006–2013), in a section of the exhibition curated by Cindy Sherman: an array of almost a thousand found photographs of babies and young children, in which—according to the conventions of nineteenth-century photography—the mothers, while posing in the pictures to keep their offspring still, were hidden from view. The archive is arranged according to different methods of erasure—the mothers are covered with a cloth (reminiscent of a burqa), or crouch behind a chair, or their faces are scraped off the image altogether. At the same time, the contents of the long vitrine seem to function as a study of the conventions of photography, a survey on particular aspects of the discrimination of women in Western societies, and an ode to (painfully invisible) motherly love.

But the need to systematically map any given field—a constitutive principle of the encyclopedia—comes into sharp contrast at times with the nature of what is surveyed. Thierry De Cordier’s darkly realistic seascape paintings (shown alongside Richard Serra’s Pasolini, 1985, in one of the exhibition’s most powerful pairings) allude—both in form and subject—to the impossible struggle to categorize the naturally flowing, the amorphous. Camille Henrot’s mesmerizing video montage Grosse Fatigue (2013), taken from the Smithsonian Institution’s archives interspersed with her own personal footage, attempts to systematize manifold creational narratives.

The Giardini’s central room points at another key element of encyclopedias. Its centerpiece is Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s Plötzlich diese Übersicht (1981–), a collection of over a hundred small clay sculptures offering a depiction of the world through an arbitrary selection of significant minor events. From Einstein’s parents staged at the moment after the conception of their son, to Jacques Lacan first seeing himself in a mirror at age two; from a group of potatoes (asking how they ever got to Europe) to Jagger and Jones going home satisfied after writing “I can’t get no satisfaction;” it is an ironic and yet oddly sensitive encyclopedia of banal mysteries and everyday epiphanies. The display, however, is particularly significant. In 2008, when Gioni showed the piece in a Fischli and Weiss retrospective he curated in Milan, he arranged the sculptures’ individual plinths in a linear sequence of groups, suggesting both an intrinsic order and a path the viewer could follow to obtain a complete experience of the work. In the Biennale, however, these are scattered around the room, giving the labyrinthine feeling of a mass of knowledge that could never be fully apprehended. No matter how much you look and read, there’s always something you’ll miss.

The extent of the curator’s intervention in this exhibition is even more notable in moments when Gioni’s curatorial decisions suggest an encyclopedia where none was intended. This is the case with Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits of black men and women in everyday poses—blurry and evocative, clearly in the tradition of portrait painting. Their surprisingly critical element—belonging to a codified visual canon while critiquing the discrimination implicit in it—is strongly apparent in the individual works, and yet it is subsumed in their being presented as a series. The viewer is encouraged to look at the structure of relations between paintings—their differences and similarities: the “system” of knowledge they compose—rather than consider them individually. A collection of encyclopedias (and this, in part, is what Gioni’s exhibition is about) is concerned with systems: the curatorial stress on this structural aspect neutralizes the criticality of the elements composing it, in this case privileging Gioni’s interest in form over Yiadom-Boakye’s interest in content.

An interesting thing about encyclopedias is that they reveal as much about their author as they do their subject, laying bare the ambitions, ideals, and conceptual framework of the person compiling them. This may account for the remarkable presence of works related to mysticism and religious experience defined in the broadest terms—from anonymous Tantric drawings symbolizing, in simple colors and abstract shapes, a quest for wholeness, to Guo Fengyi’s intricately detailed paper renditions of her practice of Qigong.

This subjective side of encyclopedias, more importantly, explains the obsessive quality found in many of the exhibited works. For Solo Scenes (1997–1998) the late Dieter Roth filmed himself daily in his last years while performing banal tasks and meticulously cataloged each tape; Kohei Yoshiyuki, in his series “The Park” (1971–1979), photographed hundreds of couples having intercourse in parks at night, focusing however on the voyeurs… while being one of them himself. Each of these endeavors bespeaks a kind of mania: the impossible quest for exhaustiveness of their encyclopedic projects appearing as the only palliative against such obsessions.

Gioni’s exhibition surveys these attempts with an extremely curious yet empathic gaze. In so doing, it deliberately mixes so-called “professional” artists with “outsider” artists; people for whom the creation of images was a side-effect of another activity (such as Rudolf Steiner’s lecture diagrams from 1923), people for whom it was a momentary escape from madness, loneliness, and pain. There is a lot of such pain in the show.

By blurring the codified line between the categories—or, rather, by questioning its meaningfulness altogether—Gioni seems, on the one hand, to reverse the hierarchy traditionally favoring artists with formal training. The museums, biennales, and projects mentioned in such artists’ biographies could make their research appear frivolous or unnecessary in comparison to the tragedies and stints in mental institutions dotting the histories of their less-celebrated “colleagues.” On the other hand, this move further asserts the primacy of the curator when it comes to constructing meaning from an array of visual material, whatever the intentions of their makers might have been. In the context of benchmark exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale, this could be seen as a confirmation of the increasingly authorial role of curators—one championed by Gioni’s own professional practice.

And yet, in choosing Auriti’s palace as a model, Gioni seems to align himself with the “outsider” end of the spectrum, and to pre-emptively frame his own project as utopian, relegating it to the realm of imperfection, if not failure. Much as the encyclopedias it amasses—incomplete, idiosyncratic, yet purportedly systematic—“Il Palazzo Enciclopedico” is a powerful tribute to fallibility, to the necessity of partiality (and ignorance) as the inevitable outcome of any quest for knowledge.