Anyone who grew up in the 1970s and watched the Children’s Television Network/PBS educational series Sesame Street was subliminally prepared for the gamut of conceptualism in (contemporary) art. No character prepared one better than the “Mad Painter,” who popped up in the unlikeliest of places in his Chaplinesque bowler hat and signature striped shirt to paint the “number of the day” on an unsuspecting surface or person: bald or balding pates were regularly and hilariously victimized. They always realized their fate all-too-late and then chased the Mad Painter out of the frame, oftentimes with the reel sped up to look like the Keystone Cops, or, again Chaplin, to the accompaniment of a vaudevillian or ragtime/honky-tonk piano. While Július Koller (1939–2007) was making his “U.F.O.-NAUT” works long before the Mad Painter ever went on air, whether Rirkrit Tiravanija’s channeling of Koller performs a double-entendre of channeling the Mad Painter is the question. Tiravanija, born in 1961, is certainly of an age and spent time growing up in Canada where Sesame Street was a television staple in the 1970s. This exhibition is essentially a re-presentation and re-framing of Koller’s “U.F.O-NAUT” works by Tiravanija—to claim a sympathetic conceptual predecessor.

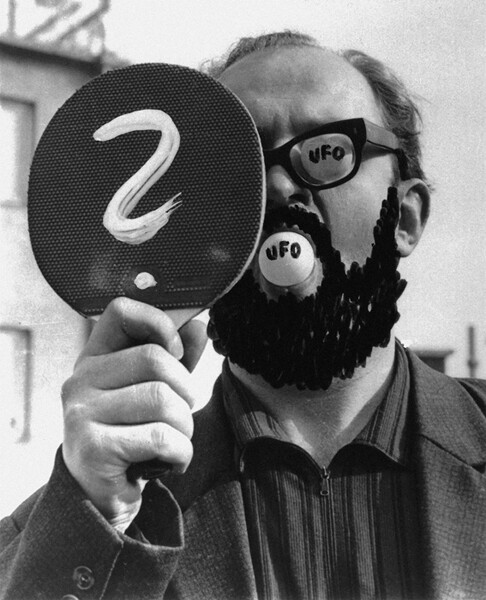

The Mad Painter comes to mind because in the “U.F.O.-NAUT” series Koller paints question marks on unsuspecting surfaces not usually associated with art, and particularly, his penchant was for table tennis paddles and tennis racquets. (Though Koller would hardly have made the connection in 1969 when he commenced the series, table tennis paddles look similar to the paddles used for bidding at auctions, and one could well imagine him performing agitprop at Christie’s or Sotheby’s). In one especially Mad Painteresque black-and-white photographic performance documentation Otáznik (Anti-Happening, 1969) Koller paints a question mark onto the surface of a clay court, using a chalk-line marking roller. In the photographs Question Mark 1–4, Anti-Happening (also 1969) he inscribes the mark on the court using his hands and feet. The photographic portrait that follows in 1972—Univerzálna Fyzkultúrna Orientácia (U.F.O.)—depicts Koller in full tennis whites, including a handsome cable-knit sweater, with a UFO club emblazoned on his chest and question mark on the racquet strings.

Why tennis, one might ask? I would hazard to reflect on the fact that the most famous thing about communist Czechoslovakia at that time was the tennis player Jan Kodeš who won successive French Opens in 1970 and 1971 and then Wimbledon in 1973, and was twice runner-up at the US Open in 1971 and 1973. As an artist trying to bridge the divide between the Warsaw Pact countries and the rest of the world—where a more public conceptual practice was unfolding—sports seems a reasonable and universal signifier. Conceptualism was always contrary and as universal as sport might be it is considered antithetical to art. For this reason, it seems an all-too-fitting signifier-cum-vehicle. (Futhermore, at the time that Kodeš was at his peak, one of his greatest rivals was the Romanian Ilie Năstase, so there was a real Cold War conversation going on here.) Tiravanija’s own principal contribution to the exhibition is a set of table tennis tables, each of which is emblazoned with the text “MORGEN IST DIE FRAGE” [Tomorrow is the question], which lends the works their “untitled” title Untitled (MORGEN IST DIE FRAGE) (all works, 2012). Considering this contextual and historical setting, coupled with the fact that Tiravanija is by heritage Asian, the tables evoke something of the same era of 1970s Cold War relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China known under the moniker “Ping-pong diplomacy.” The term described the sending of a team of US table tennis players to China in 1971 to play in a tournament that was promoted under the banner “Friendship First, Competition Second” that acted as a forerunner to President Richard Nixon’s visit to Mao’s PRC in 1972.

Of course the nature of much of Tiravanija’s practice is based on terms of “hospitality,” whether that described by Jacques Derrida or Donna Haraway, as embodied by the collective farm/residency that Tiravanija is involved with in northern Thailand, or, in the case of his cooking, Charmaine Solomon. There are also his collaborations with the likes of Superflex and the unitednationsplaza project in Berlin and its international offshoots. Indeed, he could happily make a future set of tables including the text “Friendship First, Competition Second.” The spirit is certainly reflected in the way he embraces Koller within the framework of the exhibition at Galerie Martin Janda; and in the way visitors at the opening played table tennis together. The gallery also plans a friendly tournament on the closing weekend.

Moreover, a great deal of friendliness emanates from the 2013 performance Untitled (Remember JK, Universal Futurological Question Mark U.F.O.) that assembled a diverse set of people to stand in the form of a question mark on the square in front of Vienna’s St. Stephen’s Cathedral on a drab early-March Saturday morning, to be photographed aerially. Coincidentally, the event took place at the same time the Conclave of Cardinals voted on the new Pope, lending some unintended politics (and certainly poetic justice) to the action. Light on numbers, the assortment of gallery staff, family, and friends who had gathered were joined by a group of Italian tourists who, in the spirit of friendliness, ensured critical mass—and a proper testament to Koller. I am sure that if U.F.O.s happened to land, despite the weather, the aliens would have been impressed.