There is a morbid fascination in observing cinema’s material world. That world which stands still, which is not affected by the transience of the moving image; which can be observed for the desired time and angle, and which steadily reveals itself upon our eyes. This possibility is the revenge of the fetishistic spectator, who desires to go beyond the threshold of the fleeting cinematic image, and see, touch, or even possess those things that appeared in it.

It can be awkward to have access to such concrete reality because the pleasure of watching films is often more related to the gaze of the ephemeral than with the extended observation of a fixed object. These ambiguous feelings cohabit at Kate MacGarry gallery, whose current exhibition presents a series of drawings, paintings, and objects related to the film works of Jeff Keen, a cult figure of British experimental cinema.

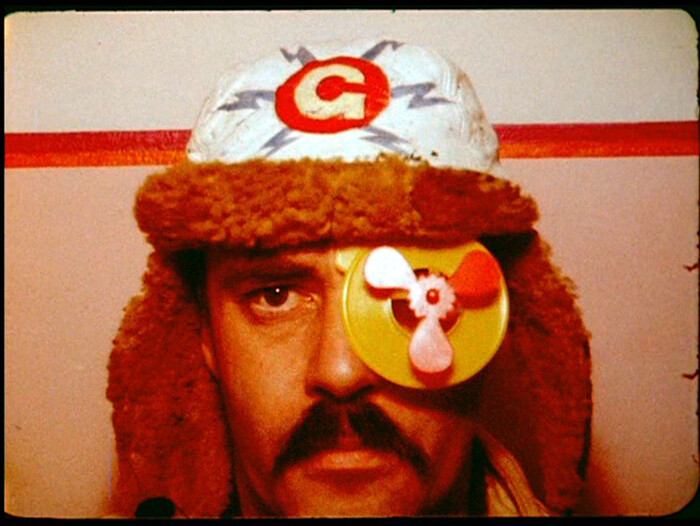

Keen (b. 1923), who passed away in 2012 after having made over seventy short films and videos, could well be considered a pioneer of the postmodernist imaginary. Keen’s films present an intricate (and often excruciating) babble of images, sounds, and gestures that are combined, distorted, and corrupted at a very accelerated speed—some of them being quite exhausting to watch due to his delirious editing. In many, cut-out comic superheroes, little plastic toys, letters, soldiers, marker-drawn bombers, found-footage segments, and pin-ups superimpose and annihilate the other elements. In other works, Keen’s everyday and domestic environments of his hometown of Brighton were used as a backdrop, and he played many of the roles himself, along with his partner Jackie Foulds. Other characters seemed straight out of a hallucinatory theater, the “Ethereal Theatre of the Brain,” as he wrote in his poem “RAYDAY” in the early 1960s.

Combining of the residues of his experience serving in WWII with his passion for Surrealism, Keen’s world is as impenetrable and indescribable as a nightmare. In the props, drawings, collages, and paintings exhibited at Kate MacGarry, Keen’s Dada-like propensity for emphasizing the illogical and the absurd is ever present. However it is the sound of some of his best-known 16mm films (Cineblatz, 1967; White Lite, 1968; Marvo Movie, 1967; Meatdaze, 1968; Rayday Film, 1968/70; and 24 films, 1972/75), presented, rather unfortunately, on a flat screen at the entrance of the gallery space, which lends the overall tone to the exhibition. An equally cacophonous blast greets the gaze with the pairing up of the comic zigzag of the painting Lightning Bolt (1970) with two helmets—respectively ARTWAR (1990) and Mister Soft Eliminator (1981)—and the triptych OMOZAP Triptych Box (1980), which combines the portability of Duchamp’s boite en valise with a violent accumulation of layers and iconoclastic materials that becomes a decadent, distorted setting for the plastic Marvel Superhero (a naked muscle-man) whose presence adds a meaningless abandon to the whole assemblage.

Keen undoubtedly shares the same wavelength with Pop, but he inhabits a different frequency, closer to a disruptive, existentialist punk sprit. Some other pieces, like the red onomatopoeic Zap (1958), Plane over Target (1970), or Vietnam Diptych (1969) turn words and forms (airplanes, bombs, palm trees) into raw archetypes of a universe that is always on the verge of exploding.

The core of such blasts can be found on The Secret World of Dr. Gaz (1950–1990), a display case of all and sundry assembled by Keen’s daughter Stella: comic books, plastic robots and motorcyclists, photographs, photocopies, pinups; stencils, and drawings are displayed in an organized mess that certainly mimics, even if in a mild way, Keen’s working environment.

Despite the transposition of his chaotic surroundings to such an orderly context, Keen’s vivacity and truly personal contribution to the development of radical experimentalism in art appears to be alive and kicking. Nostalgia has been shoved even further back into the closet so that Keen’s avant-garde practice remains right where it belongs: to the future.

Note: This text—and most of Keen’s recent rediscovery—would not have been possible without the outstanding activity of William Fowler, a curator at the British Film Institute National Archive, who has written extensively about Keen and who worked on a series of restorations and a box set, GAZMRX: The Films of Jeff Keen.