Is it possible to talk about art made in Los Angeles without crediting the city with everything that makes its art unique? Why are artists in Southern California so often asked to explain how their work is influenced by its infrastructure or climate? Is “Made in Space,” the exhibition curated by artists Peter Harkawik and Laura Owens, an antidote to these tendencies or is it a symptom?

Harkawik and Owens make no claims for their selection of thirty artists, though the show’s title is uncannily reminiscent of “Made in L.A.,” the 2012 Hammer Biennial, which pitched itself as “a snapshot of the current trends and practices coming out of Los Angeles.” By contrast, Harkawik and Owens’s thirteen-point exhibition text (in place of a press release) begins with no 1: “Someone drank tea. Someone else felt that a specific kind of taco eaten at a particular geographic location was like a drug. The spices generated a certain kind of energy, or, perhaps, muscle memory. It was 2012.” It goes on to reference a litany of local legends and historical phenomena, from Peter Schjeldahl’s dismissive 1981 essay in The Village Voice about the Los Angeles art scene to O.J. Simpson’s 1994 car chase. It ends with no 13: “Two curators drove by a flip flop in the road. This was mutually lauded for its demonstrative effect. It was 2013.” At no point, however, do the exhibition’s curators admit to specific intentions.

Harkawik and Owens are both accomplished artists, and it is their right to put together a subjective and intuitive exhibition that reflects their aesthetic tastes and social allegiances. “Made in Space” does that, but it seems to want to do more. Amongst the cultural ephemera of the exhibition text are some astute observations on the nature of space in Southern California. The philosopher Elizabeth Grosz is quoted: “Space, like time, is emergence and eruption, oriented not to the ordered, the controlled, the static, but to the event, to movement, or action.”

At times, “Made in Space” coheres to engender similarly critical ideas. One room contains a pair of works by Mungo Thompson. Large mirrors printed with Time magazine’s distinctive logo and red border face each other at either end of the space creating a trippy mise-en-abyme. One is titled June 25, 2001 (How the Universe Will End), and the other March 6, 1995 (When Did the Universe Begin?) (both 2012). On the floor between them, Joshua Callaghan’s hyper-realistic series “Chicago Snow Chunks” (2012) seem to be arrested mid-melt, like once-pristine snowdrifts reduced to crusty brown nuggets of ice. With the addition of David Korty’s ceramic pitchers and Marcia Hafif’s painstaking all-over pencil drawing (August 7, 2012, 2012) the display articulates a model of the dizzyingly elastic passage of time, and ways that artists might choose exploit it. I fail to see the relevance, I confess, of an adjacent print by Allen Ruppersberg, Honey I rearranged the collection trying to make a purse out of a sow’s ear (2011), nor of Laeh Glenn’s admittedly alluring trio of small paintings. If the exhibition might benefit in many places from a stern edit, it is also likely that the curators do not feel that pithiness (or, for that matter, clarity) was ever high on their agenda.

Hafif, who is 84, is one of a number of older artists in the exhibition. (“Made in L.A.” also elected to stretch the “emerging” tag to include a number of under-represented artists in their seventies and eighties.) Hafif’s lifelong commitment to monochromatic painting and drawing is all the more impressive when one realizes that she is some fifty years older than artists such as John Seal, whose assemblage—combining an abstract painting with a sculpture of a vase of flowers and the convoluted title Orpheus Singing to Pluto for Eurydice’s Release (2013) —is installed nearby. A painting by Derek Boshier, a British contemporary of David Hockney and Peter Blake who now lives in Los Angeles, also looks as fresh as any of the younger artists’ work. The Los Angeles Collectors—Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Cycladic (2001) adheres to a feel-good, pastel pink, yellow, and blue palette that is shared by Lucas Blalock’s still-life photograph Foam II (2012) and Patrick Jackson’s oversized ceramic, Blue Mug (2013), which sits under Boshier’s painting. The mug is a poisoned chalice; up close, its spotty pattern reveals itself to be spermatozoa, and inside it holds a gunky white substance that looks, optimistically, like melted marshmallow. These works bring to mind a riff in the curators’ text on food coloring and the discontinuation of the “Baja California” flavor of Starburst sweets; too many colors, it observes, and the painting (like food) turns to shit.

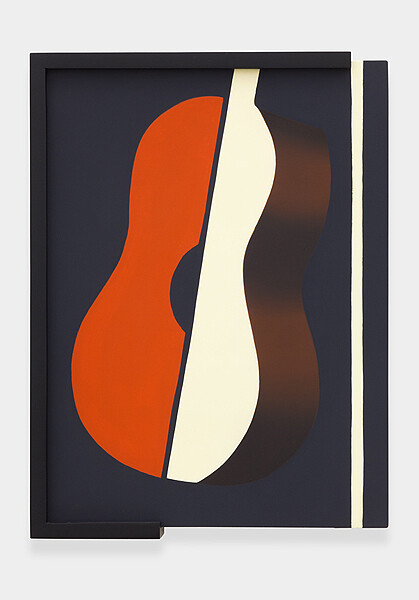

Which brings us to Jedediah Caesar’s brown Gleaner Stones (2008–2011), which run along two walls of the gallery. The single line of urethane bricks seemingly capture, visible in each, a city’s worth of street refuse. Caesar’s work is as close to urban anthropology as any in the show, and a dour cousin to Eric Orr’s transcendent abstract painting Radio Play (1990), whose media is listed as “meteorite dust, bone, radio parts, artist’s blood, gold leaf.” Trawling the (physical and metaphorical) grit of L.A.’s urban fabric, Caesar and Orr’s works suggest at least one sense in which this art is “made in space.” Paintings by Aaron Wrinkle and Rebecca Morris appear to be incidental to other, unseen processes; one of Wrinkle’s two paintings constituted the table on which the other was made, while Morris’s Untitled (#02–13) (2013) hints at arrayed pattern samples, or the kinds of perfunctory mark-making involved in architectural construction work.

But these systematic, realist, material responses are in the minority here; most striking are the vivid, fantastical, figurative images of Josh Mannis, Max Maslansky, Michael Decker, and Jesse Mockrin. Maslansky’s softly painted Dancers (2013) are engaged in elegantly choreographed three-way intercourse; Mannis’s intricately drawn scenes recall the dreamscapes of Marc Chagall even as his subjects watch videos on their Mac laptops. Space here is imaginative, erotic, temporal, and social. In this exhibition the term means no single thing; in their aversion to generalities, Harkawik and Owens suggest that space, for those living in Southern California, is much more complex, and less easily nameable, than the oft-exported clichés of freeways and sprawl.