Whenever I see a photo by Luisa Lambri, I think of a painting done by Gwen John (whose work remained in the shadows of her more famous brother Augustus until recently). It’s called A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (1907–9) and it depicts a luminous corner of her attic: a wicker chair, a vase of flowers, the painter’s blue smock, a curtained window, and a triangular patch of pale sun. Although Lambri has always been attracted to corners and radiant apertures (windows, skylights, blinds) in private, domestic interiors, that’s not what sets my free associations into play. A Corner is obviously a self-portrait, even if John has subtracted her image from the frame. She painted it for seeing herself seeing, not for seeing herself being seen by others. In 2010, Lambri titled her exhibition at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles “Being There.” “I am photographing myself being there,” she explained of the photographs from which she was so obviously absent.

It’s the “the silent presence of another person”—as Michael Fried once described it—that confronts us in Lambri’s new series of prints at Studio Guenzani (where she held her first solo, back in 2000). They bring her gaze into the pictorial and sculptural space of post-war Abstraction and Minimalism: a new territory for her after having trod the familiar ground of Modernist architecture. Since the 1990s, Lambri has been capturing signature houses by—mostly male—stars like Aalto, Mies, Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, Wright, Kahn, Barragán, and Johnson, but she did so by erasing all iconic points of reference. Her photos subvert the architectural syntax of scale, authorship, and mastery to depict instead the artist’s own emotional responses to those spaces, according to different moments and moods. It would seem that Lambri is at home with the Japanese notion of ma, which can be translated as a negative space, gap, or interval “between structural parts.” Not surprisingly, the architect with whom she built the strongest connection over the years is Kazuyo Sejima (SANAA), who invited her to exhibit in the Venice Biennale she curated in 2010, aptly titled “People Meet in Architecture.”

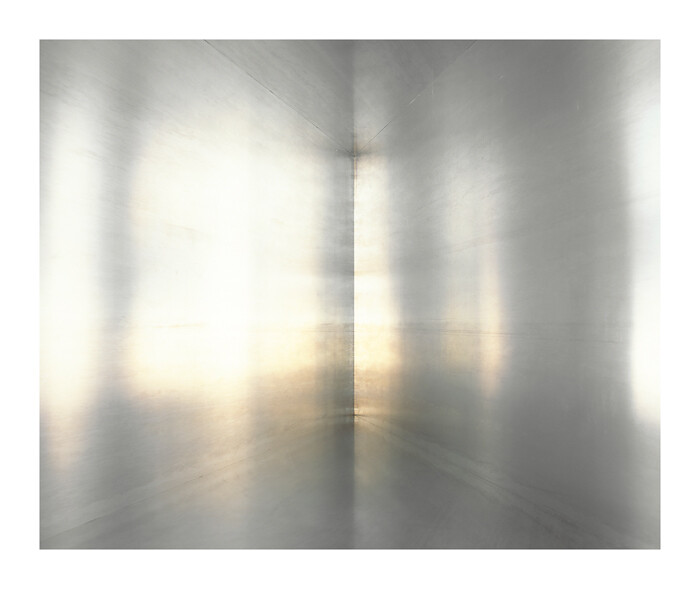

The exhibition layout is simple. In the first room, Untitled (100 Untitled Works in Mill Aluminium 1982–1986, #01) (all works 2012) is Lambri’s appropriation of Donald Judd’s eponymous work (made of structures all identical in size, though all different inside), for which he had new walls of continuous windows built in two sheds of the Chinati Foundation, in Marfa, to ensure a constant flood of light on the polished surfaces. Lambri’s subject is only the reflection, immaterial and non-accountable, blurring the borders of prescriptive grids. Furthermore, as the gallery in Milan has several windows onto the street, the framed photos are superimposed by their fleeting images too, somehow mimicking the original spatial arrangement.

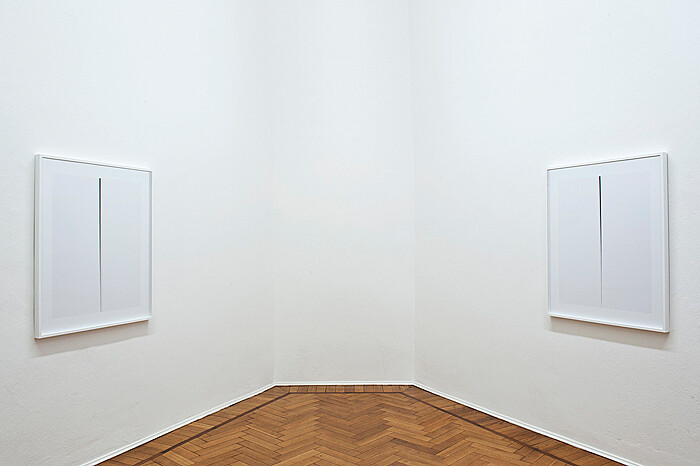

In the second room, side by side, hang Untitled (Ambiente Spaziale, #01) and Untitled (Ambiente Spaziale, #03). Two close-ups of Fontana’s classical slashes are here turned into a thin black line on a white background, as if to reduce Fontana’s “free space” back into the neat and squared package of two-dimensionality. In the last and biggest room, Lambri lined up three other versions of Untitled (100 Untitled Works in Mill Aluminium 1982–1986, #02; #03; #05) on one wall, while occupying the other with Untitled (Marfa Project, #01), a photo which captures the pink and light blue reflections of a Dan Flavin installation at Marfa, abstract and soft, with delicate, rococo shades. This small picture, which summons up the intersecting fields of photography, light, and space, works well as a climax, also because of its sensuality.

By approaching Minimalist signature artworks with the same obliterating attitude she adopts for architecture and by positioning herself up close, precisely into the kind of “intimate” relationship which Robert Morris rejected, Lambri contravenes the implicit rhetorical of power of Minimalism. As Iris M. Young wrote, “We might conceive a mode of vision, for example, that is less a gaze, distanced from and mastering its object, but an immersion in light and color. Sensing as touching is within, experiencing what touches it is as ambiguous, continuous, but nevertheless differentiated.” 1

Iris Marion Young, “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility and Spatiality,” in Throwing Like a Girl and Other Essays in Feminist Philosophy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), p. 182.