For a fair that has been around for thirty-two years, ARCO has weathered its share of ups and downs. Economic woes are at the root of the uncertain and gloomy mood that has reigned supreme in Spain’s cultural sector of late. Although the selection of galleries and visitors remains steadfastly international, many small businesses—galleries included—have been forced to shut down recently in the wake of the increase in taxes on cultural production in Spain, now at a whopping 21%. This reality haunts the current edition of ARCO. Nevertheless, one can say with relative confidence that considering the professional attendance and international perspective—focusing on the bridge between Europe and Latin America—ARCO has reached an apex. But this year’s real accomplishment is the savvy strategic investment of hosting a huge forum of “professional meetings,” for which almost every director of the most relevant museums and biennials worldwide has descended on Madrid to attend a series of working sessions by invitation only. Of this particularly high-caliber audience, one gallerist raved: “All of them are here. It has been like one continuous studio visit; the audience is better than that of a biennial!”

Besides the usual malaise that overcomes one after gaping at a floor plan with 201 participating galleries, the “surprises” of the Solo Objects section made it all more than worthwhile—after slogging through the whole fair to find them, ferreted away in strange corners—such as Christine König’s presentation of Jimmie Durham’s Cannot Explain Adequately What Happened That Night (2012). By the time I had reached the special section with twenty-one Solo Projects—all by Latin-American artists hand-picked by a select group of curators, Inti Guerrero (Costa Rica and Hong Kong), Catalina Lozano (Mexico), Gabriel Pérez Barreiro (New York and Caracas), Alexia Tala (Chile), and Cristiana Tejo (Brazil)—I was exhausted. After the low ebb of the Solo Objects section, the Solo Projects was mercifully much better, making it easy to become entranced—no hyperbole intended—by the history, magic, archaeology, and science encountered there. In particular, the imaginary museum Episodios en la vida de un museo (2013) by Argentinian artist Sebastián Gordín, at São Paulo’s Oscar Cruz Gallery, stood out. Magic realism abounded in what the artist calls his “zombie museum,” a carefully designed glass cabinet filled with curiosities.

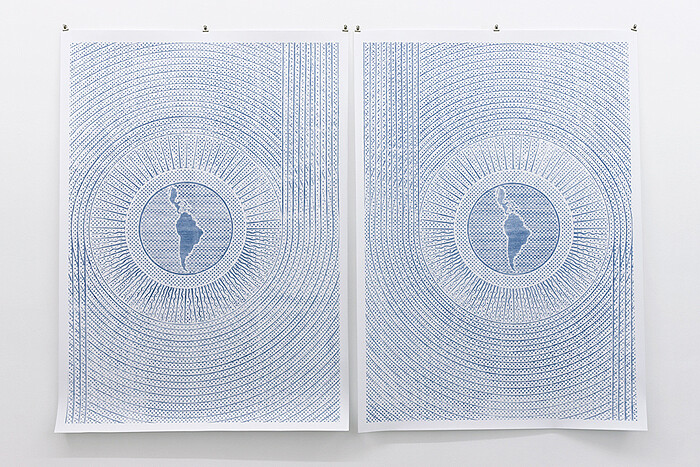

Mariana Castillo Deball’s new piece, specially commissioned for ARCO this year and part of the “Archeological” show now on display at Matadero, consisted of a series of drawings and costumes based on the Codex Tudela—a pictorial document from the sixteenth century painted by indigenous scribes. The costumes reference the chinelos, or satire masks, that the indigenous population used as a response to the prohibition on their taking part in carnivals. Further on, Colombian artist Álvaro Barrios—represented by Henrique Faria Fine Arts, New York—presented an installation of blue prints hanging from the ceiling that were meant to signify the longitudes and latitudes of the sea of the Malvinas (which, to make things more complicated, re-enact a 1971 installation made by the artist called “El mar del Caribe”) with portraits and an anachronistic dialogue between some of the ladies of the Falklands War pasted along the wall: Queen Victoria, Queen Elizabeth II, Margaret Thatcher, and Eva Perón.

Two other projects had me hooked, demanding a more careful reading than I could give to them during such a marathon: the work of Julia Rometti and Víctor Costales at Galerie Jousse Enterprise, Paris, and François Bucher at Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City. Both are subtle, conceptual takes on broad fields of knowledge—from obscure literature to anthropology and psychotropic drugs. The writings of Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro are one of Rometti and Costales’s main sources of influence, whereas Bucher took refuge in the esoteric writings of Nostradamus (via Daniel Ruzo’s investigations), among many other references.

Pushing onwards, the Opening: Young Galleries section featured twenty-five galleries from Asia, America, and Europe, which have been around for less than seven years. Participants were selected by Manuel Segade, independent curator and critic and Veronica Roberts, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Blanton Museum in Austin, Texas. There Galleria SpazioA from Pistoia, Italy displayed a delicate collection of artist Chiara Camoni’s assemblages of quotidian objects, pretty and teasingly witty. Her Smile (2012), for example, is a simple arrangement of crystals in a semicircle over a pile of blank sheets of paper. Nearby, I stumbled into a rather stoic booth, which contained a riddle of its own. It was actually a performance by Sander Breure & Witte van Hulzen of a fake gallery, called Ansgar Lund, presented by a real gallery from Amsterdam called Tegenboschvanvreden. The next thing to catch my eye also seemed a curiosity: somebody on the floor arranging colors one by one, into a grid, from a bag of confetti under the table in the middle of the Bacelos booth (a gallery from Vigo, Spain). This turned out to be the work Arrebato de tedio [An outburst of tediousness] (2013), by Spanish artist Fermín Jiménez Landa; a fragile gesture, fragmented, and yes, somehow alluding to our dire economic situation.

After realizing that hours had passed, and there were at least a hundred more galleries to check off the list, I decided to edit my tour and head straight for this year’s featured country section: Turkey. Focus Turkey included works selected by Vasif Kortun, director of research and programs at SALT Istanbul (with assistant curator Lara Fresko). There I was happy to find Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s film Murder in Three Acts (2012) at NON gallery, which I had missed last year at Frieze, London, as well as a work by Meriç Algün Ringborg, a little piece with stamped dates, intimate and personal, reminding us of the tedious and long waiting times to get a visa, destination known and bureaucracy unbound.

But ARCO is far from over. The program of forums and panels began Thursday with the Second European and Ibero-American Museums Meeting. Apart from that, some of the more than 150 critics and curators invited for the previously-mentioned private gatherings will share their conclusions in public sessions in order to interrogate the current state of the arts, with themes ranging from gender and cartographies (Thursday), to biennials as generators of knowledge (Friday), and the role of institutions and their collections (Saturday). Already with a contemporary Stendhal Syndrome (Look that up! Who’d have thought that art-fair malaise would have been felt by a nineteenth-century author!), I leave the fair with a familiar feeling, the Documenta effect. That association, in any case, gives me pause and makes me think that I should definitely not stop there. Let the discussions commence.