There are portraits of two women in this exhibition by Miroslaw Balka and Roni Horn. Who knew that a portrait of a lady could reveal so much, that a portrait of a lady could become a portrait of the artist? It’s tempting to read these images as condensed biographies reflecting on individual art histories. Set up in the same room, they collide in an uncomfortable tête-à-tête. How appropriate, for a show titled “Gespräche über persönliche Themen” (Conversations about private themes), jointly conceived by the artists and installed like a neat conversation piece. The pairing marks the last episode of an annual program based on “duets” (Daria Martin and Anna Halprin; Michael Fliri and Asta Gröting), introduced by Raffaella Cortese to celebrate the opening of a twin space of her gallery on the same street.

First we meet Márgret Haraldsdóttir, who emerges from the hot pools of Iceland and whose face is as subtly changing as the clouds in an overcast sky in Untitled (Weather) (2011). Horn—who identifies with the nature of Iceland, a country she has been visiting regularly since her early twenties and made the chore of her personal “encyclopedia,” To Place (1990–ongoing)—asked Márgret to pose again for this series, which replicates in detail Horn’s signature work You Are the Weather (1994–96). Installed at eye level, Márgret looks straight back at us, mirroring the presence of another “you.” Fifteen years on, Márgret still looks hauntingly beautiful, so there’s no nostalgia at play here. But for those who know and remember You Are the Weather, the memory of her former younger self slips hesitantly in-between us and the countenance we scrutinize, thus measuring the passage of time. Horn duplicates our visual experience with the simple device of repetition, rendering it impossible to define individualities in terms of single identities. She is, unceasingly, the artist that makes Things That Happen Again: For a Here and a There (1986–91), to quote the title of one of her earliest pieces, created for the Chinati Foundation in Marfa in dialogue with Donald Judd, who was a friend and collector of her work.

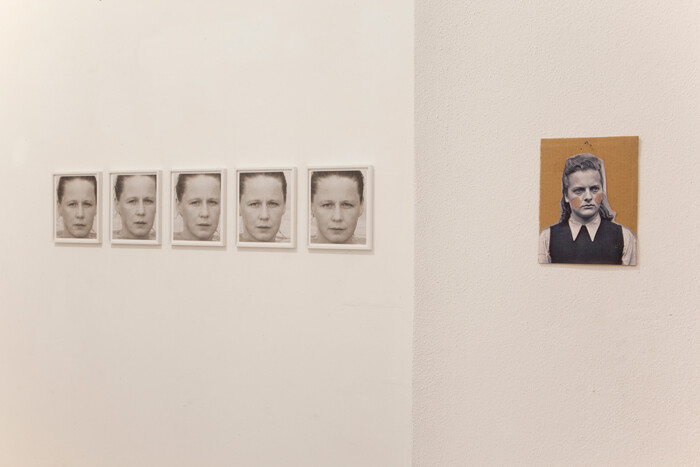

Then there is Irma. She’s all alone, next to the wall’s edge, around the bend from Horn’s Márgret, and enigmatically titled 2x(250x200x100) + Irma (2006). Irma is Irma Grese, a sadistic female warden employed at Ravensbrück, Auschwitz, and Bergen-Belsen, who was nicknamed “The Beautiful Beast.” The original mug shot was taken in August 1945 while awaiting trial (Grese was sentenced to death by hanging at 22), and in Balka’s version the black-and-white image is truncated and glued on a piece of cardboard. Balka’s added a droll touch, dabbing make-up over her cheeks, blushing rounds of carnation pink in response to our gaze. Irma faces two plain MDF boards installed in front of her, a minimalistic gesture that undoubtedly grants viewers a temporary shelter, a sheepish way of avoiding involvement and direct confrontation with all the horrors Irma stands for.

Balka was born near Warsaw in a city whose large Jewish population was deported to Treblinka. It’s a fact that courses through his work, loaded with memories and traumas, both collective and private. An old motorcycle helmet, for example, found by the artist in the countryside and roughly polished to scrape away the varnish (15x22x19, 2006) is nailed to the ceiling here like a sinister relic.

The exhibition triggers free associations on all the personal themes Balka and Horn seem to share: age (they were born, respectively, in 1958 and 1955); fathers with tough jobs (Horn’s dad had a pawnshop in Harlem, Balka’s was a headstone engraver); thoughtfully restrained emotional contents; a keen interest in the legacy of Minimalism, though subverted by an idea of sculpture as a corporal, or even carnal, space; the recurrence of the artist’s body as medium (think of Horn’s paired self-portraits in her A.k.a. series (2009) and of Balka’s habit of producing works in accordance to his height, weight, arm length, shoe size, etc.). Their works echo each other, and the layout they have collaborated on enhances the correspondences. In the center of the gallery, Balka’s 200x100x200 (2012), a ghostly doppelgänger of his own wardrobe rendered as a skeleton of ordinary white plastic strips and steel staples, is immediately mirrored in Horn’s Double Möbius (2009), a gleaming ribbon in pure gold, dangling on a nearby wall, in which the illusion of a mobius strip’s two sides is here garishly denuded. In the new gallery space, Balka’s pillar 50x50x91 (2012), a block of concrete with three inlaid aspirin pills, suggests the necessity, and likewise the inanity, of pain killing, which finds a nice counterbalance in Horn’s dense Black Asphere (1988/2006), set on the floor. It’s a sculpture in solid copper, and, in an interview with Collier Schorr (1) the artist describes it as providing “the experience of something initially very familiar, but the more time you spend with it, the less familiar it becomes. I think of it as a self-portrait.” The round object on the floor here, you see, is only apparently spherical—a good metaphor for the playful doubling of all the works exhibited here… almost.

1. Collier Schorr, “Weather Girls. An interview with Roni Horn,” frieze (January–February 1997), available online at: www.frieze.com/issue/article/weather_girls/.