Much can be—and, of course, has been—said about the role of Art Basel in the global art market. It’s a fair, after all, that can turn certain “peripheral” cities into cultural centers. What was Basel, what was Miami, before the advent of the art fair? In particular, Art Basel laid down the blueprint for turning a beach town for retirees into a world-class city replete with sophisticated art venues. Surely during a few concentrated days, checkbooks are flung open as widely as the doors to some of the city’s venerable collections. Yet scores of art viewers attend the fair not to buy art, but to see things they rarely have the chance to experience otherwise, and even to be inspired.

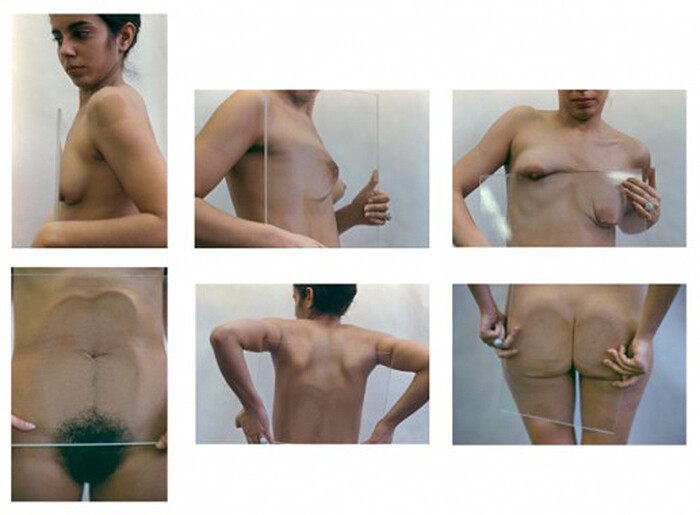

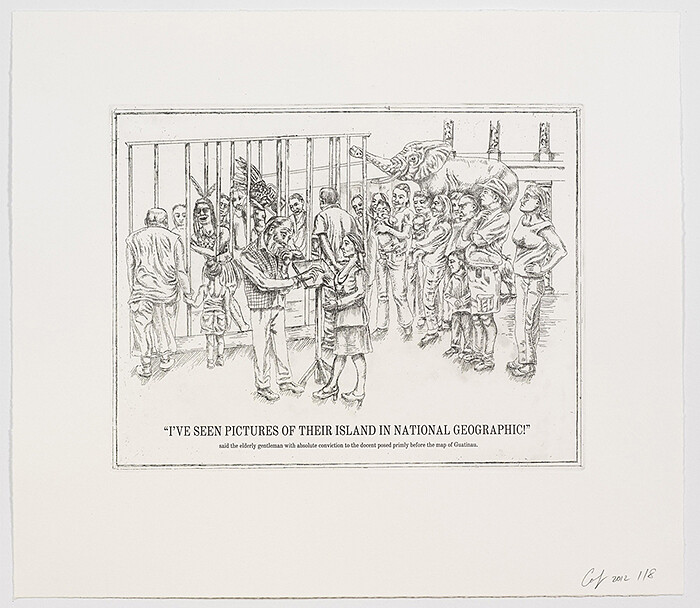

During the brief time I had to scour the aisles and booths of the 2012 fair—ABMB’s eleventh iteration—I was struck more than once by galleries who had chosen to exhibit challenging, politically-charged work that is very arguably central to the evolution of art in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Take, for example, Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints) (1972) pulled out of the archive by Galerie Lelong. Typical Mendieta photos, we see her naked here, with plates of glass squashed up against her breasts, torso, and back as the focused subjects of a see-through tableau. Mendieta worked hard for her place in twentieth-century art history, and though circumstances surrounding her death remain an enigma, her work stands on its own, no gory biographical details necessary. Likewise, Alexander Gray’s booth was a well-curated selection worthy of any museum. Gray put together some beautiful sculptures by Luis Camnitzer, historical “Lynch Fragments” from Melvin Edwards, and a series of nine prints, hung in a grid, by Coco Fusco. The latter focus on our troubled history with Native Americans, operating with an ironic distance underpinned by naughty humor. A darling of forward-thinking academics who has also played an important role in the New York Art scene for decades, it was refreshing to see Fusco’s sharp work—with its biting edge—within the context of the big fair.

Across the convention hall, in New York gallery CRG’s booth was another striking piece, this time by the Lebanese duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige. The work, Circle of Confusion 5/5 (1997), depicts an aerial photograph of Beirut. Buildings rise out of the rocky land, jutting out into the Mediterranean. But only when one approaches the tableau up close does it become clear that the large-scale image is actually comprised of hundreds of adhesive-backed squares, like pixels that together form the cityscape. Viewers are encouraged to remove individual pieces, and when I did, a large mirror was revealed underneath. Each fragment, each snippet of coastline or generic gray of the urban cityscape has “Beirut does not exist” stamped in both in English and Arabic on the back. Beirut was a thriving cosmopolis for much of the twentieth century, but since the 1970s, it has been shackled by violence and loss, the constant threat and reality of war—a perspective subtly underlined by the aerial view of the city, bird’s eye or missile’s eye. Here, as Beirut is deconstructed by our own hands, the image of a city gradually reveals itself to be a reflection of ourselves.

This year’s Art Nova section also featured a number of galleries that presented tightly curated and well-conceived booths that held their own against the established powerhouses. Lombard Freid brought together Kemang Wa Lehulere, Nina Yuen, and Lee Kit to create a booth as much as about the difficulties of daily life as about art. Lehulere’s work is a powerful backdrop to the fair as a whole, as it shows personified characters and schematic images detailing the existence and legacy of past brutalities (notably the history of Apartheid in South Africa). The booth is also livened by a personal and quirky piece by the young filmmaker Nina Yuen titled Mr. President (2012). Yuen’s mind flows in a stream of consciousness like her more mainstream counterpart Lena Dunham (of HBO’s “Girls” fame). In the video, Yuen looks at the camera directly and muses about daily life as she offers up images of flowers and thoughts about love; I am oddly heartened to take advice from someone so young and yet so sage.

One of the sections of the fair that seemed to pack a particular punch this year was Art Kabinett. Nestled within a specific gallery’s booth, Art Kabinett is a curated portion of a gallery’s presentation that gives gallerists the opportunity to present well-researched or thematic groupings of their artists. I suspect, at the same time, that it is meant to add intellectual heft to the dealers’ overall programs and solidify their influence outside of the machinations of the art market. Two of these curated displays seemed particularly compelling to me. Galerie Krinzinger, a mainstay of the Viennese scene and one of the few galleries to focus on performance art in the 1960s, created an exhibition of the work of the Berlin-based artist Kader Attia. Attia carefully chose historic prints and contemporary newspaper clippings in order to link past atrocities with their contemporary counterparts. In one grouping of these images, men dressed in Middle Eastern attire walk proudly with a caged man atop a camel. The article below it recounts one of the many instances when the CIA realized that it would be investigated for the sexual torture of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib facility in Baghdad. At the end of the room, just in case we missed the point, Attia hung a mirror with a short quote from philosopher and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi: “The shame of being a human being.” Clearly the metaphorical message is that we too have blood on our hands.

Another installation that seemed uncharacteristic of a contemporary art fair struck me as poignant and suggestive of the eccentric but informative exhibitions one normally finds in museums. Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, one of those blue-chip galleries on 57th Street that you’ve probably never heard of, organized an exhibition of works by the four Duchamp siblings showcasing their varied artistic output. Even to this day, it stuns that one family could have had such an enduring impact on art.

Despite all the work I was able to take in during the preview day at the fair, and the renewed enthusiasm I began to feel for this storied pillar of the art world, it was two conversations with two different friends that really helped me look at Art Basel Miami Beach the way an artist might. One talk involved a friend who teaches art in Chicago. He explained how—when he was a graduate student—one quick trip to the fair enabled him to experience much of the contemporary painting he was trying to recreate and emulate at the same time—from Michael Krebber to Wilhelm Sasnal to Barnaby Furnas. For this compression of time and place, he said, he was grateful to Art Basel. A fantastic early John Baldessari that I spied tucked away in the booth of Marian Goodman could also be considered a masterpiece of influence for much of what artists make today. The second conversation happened just as I was leaving the fair; I ran into a colleague whose eyes glowed when I asked how she was. “I just saw the most amazing Milton Avery painting [at Hirschl & Adler Modern]. It was so inspiring; I can’t wait to get back to my studio.” This (and everything else) is why Art Basel is such a big deal.