September 7–November 11, 2012

In 1973, Hollis Frampton sent a letter of protest to the curator of MoMA who had asked him about the possibility of doing a retrospective of his work, “for love and honor and no money.”(1) The working conditions of artists may not have changed much today, but perhaps there has been a shift in the way the problem is approached. Theaster Gates’s “My Labor Is My Protest” at White Cube, Bermondsey, is less about protest as strike, or critique via deconstruction, than the positive production of social change through work: that is, labor as protest.

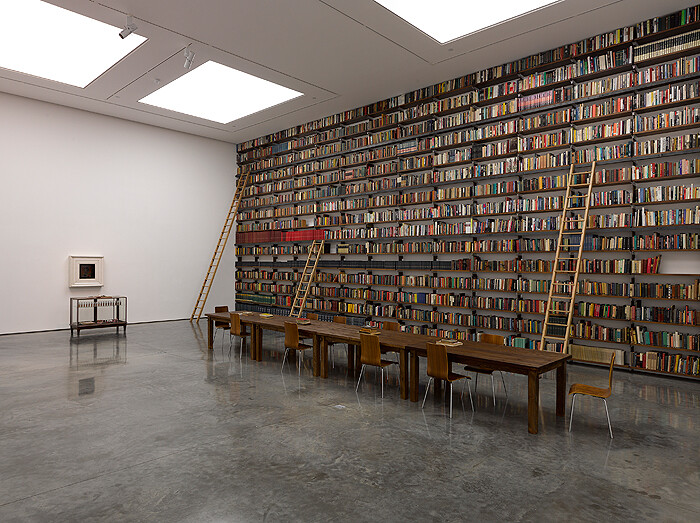

This notion of labor as a form of protest is perhaps most evident in the exhibition’s reference to Johnson Publishing Company, Chicago, most specifically in the works Johnson Editorial Library (2012) and On Black Foundations (2012). JPC is the largest African-American-owned publishing firm in the United States; they are the publishers of Ebony and JET magazines (2) as well as the owners of Fashion Fair Cosmetics, a cosmetic line created in 1973 and now the largest Black-owned cosmetics company globally. (3) Founded by John H. Johnson and Eunice W. Johnson in 1942, JPC combined humanitarian and industrial affinities, utilizing entrepreneurial business as a means to reinstate civic rights and promote social change. JPC’s self-financed 1954 film, The Secret of Selling the Negro Market, selected here by Gates as part of the exhibition’s film program, promotes the economic power of the African-American demographic. Against dismissing the sublation of civil rights into consumer rights, “My Labor Is My Protest” proposes business as a mode of collaborative critique. A political space where people make things, invest narrative in those things, and sell those things.

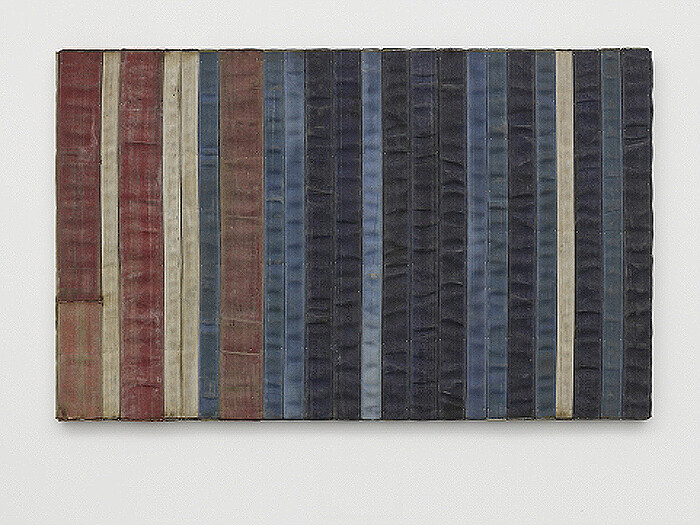

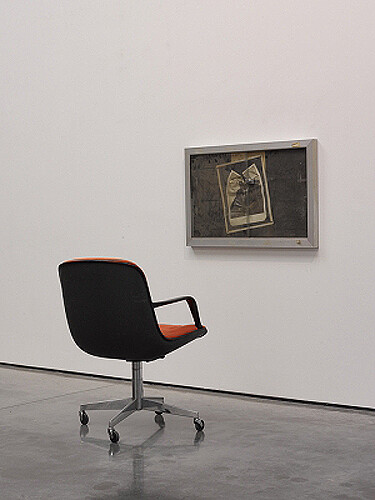

This narrative investment is clear in the objects presented. Outside the gallery My Labor is My Protest (2012), a 1969 yellow Hahn fire truck marred by blotches of tar, stands on show. A further video of the tarring of the truck can be seen inside the gallery. Fire trucks like this would have been controversially used to disperse the race riots of the Civil Rights movement. The use of tar has several connotations. Tar is a preservative used to waterproof, it can be understood as a racist, slanderous term, and it can also denote a sensitive or easily aggravated situation. It is also a reference to Gates’s father, whose work as a roofer during the 1968 Chicago riots, constituted, for Gates, an alternative form of protest, a critical productivity in the face of oppressive disenfranchisement. It is an effort symbolized in Raising Goliath (2012) which appears to suspend a huge 1967 red Ford fire truck against a full back catalogue of JPC magazines and fire hoses in one of the gallery’s oversized interior spaces. Smaller painting and tapestry works, like the tar-covered Roofing Exercise (2012) and the decommissioned, stitched red, white, and blue fire hoses of Gees American (2012) seem to gesture more specifically toward the transformation of obsolescence into cultural equity. While at the same time, there appears to be mourning for the loss of political agency in A Maimed King (2012), a single chair facing a crumpled Martin Luther King image in a dusty public display case, “I heart” drawn in the dust.

“My Labor Is My Protest” is not just about the production of artworks though; it is far more centered on how art production relates, via distribution and exchange, to the creation of communities and markets. Gates fully invests in art’s transformative potential as fetish to generate revenue for his larger social and cultural collaborative projects. The most well-known of these is The Dorchester Project (2009) on Chicago’s South Side, a group of houses acquired by Gates and repurposed as, amongst other things, a library of 4,000 volumes from the now-closed Prairie Avenue Art and Architecture Bookstore, a 60,000-strong slide collection from the University of Chicago’s Art History Department, and a Soul Food Kitchen. That these unwanted collections have been re-housed is perhaps less interesting than the way in which they are used to create Minority Business Enterprises; businesses which, like JPC, are over 51% owned by members of ethnic minorities. These enterprises then run training schemes, utilizing the free labor of graduates in need of vocational experience to train unskilled, unemployed local residents. Such not-for-profit engagement with the mechanics of policy attempts to use art object production as a means toward the creation of an incentivized workforce, rather than the other way round. The extent to which this labor can be understood as protest is, of course, tempered by the workers themselves. Labor as protest is not about producing artworks, or even building cultural centers, and it is not about the appropriation of houses or land: labor as protest is about the appropriation of agency itself. (4)

To think of the phrase “My Labor Is My Protest” in terms of agency poses the radical possibility for an art practice sustained through objects and not just because of them. Gates originally trained as a potter, and it was the lack of studio resources that led him to begin to consider issues of social policy, craft, and space. If the transformative relationship from dirt to clay to art is self-evident, then the issue is not the availability of dirt but the agency required see it as other than this; in other words, the care that brings clay and spirit together into life.

1. http://hollisframpton.org.uk/frampton9.pdf 2. http://www.johnsonpublishing.com/page.php?id=13 3.http://shop.fashionfair.com/v/pxd/aboutus.html 4. http://mica.vidcaster.com/bfMe/theaster-gates-february-8-2012/