“Welcome to my life” is written in large letters on a wooden board, announcing the uphill spill of an urban landscape made of brightly painted hollow bricks. Meanwhile, further multilingual signs—many not without humor—ask so-called favela tourists for donations. It’s been at least since the year 2007 that the Project Morrinho was made known to the international art audience, when this initiative of young people from a favela district in Rio de Janeiro was invited to participate in the 52rd Venice Biennale. Having begun as a survival strategy of children, and having changed the reality of life in this community, today it is a recognized “Favela Art Project,” which enables inhabitants to narrate their own living conditions amidst a prosperous society 1, beyond violence and poverty and from the perspective of the production of desires. That is to say, desires do not only exist in one’s imagination; rather they create realities on their own terms, which can change the lives of all involved.

But what does this project have to do with the 30th São Paulo Biennial? With “The Imminence of Poetics” being the main leitmotif, this year’s artistic director Luis Pérez-Oramas and his curators Tobi Maier, André Severo, and Isabella Villanueva examine visual poetics as both the language of the contemporary and as an archive of the future. They are guided by the poetics of territories, ideas of languages, the reactivation of conceptual traditions, and the subjectification of sonic landscapes. By drawing on the concept of imminence, the curators have created a conceptual framework of (im)possible correlations. This creates an ambiguous relationship between the curators themselves and the 111 artists 2 (with more than 3,000 works, of which 1,500 were newly or reproduced for the exhibition) and the audience as well. The curatorial principle could perhaps be paraphrased as one of permanent addition, branching into infinite artistic universes. In a good old conceptual tradition, voluntary participation of the spectator is kept at arm’s reach when constituting content. The exhibition architecture, however, employs a more classical system of white cubes, which interlock within each other. The inner core of the 30,000 m2 Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion by Oscar Niemeyer was left open, thus revealing the view between the three floors and generously establishing lines of sight. In a similar way, 30 posters—which have been circulating as the bookjacket of the catalog—were developed in a workshop to compose the Biennial’s visual identity.

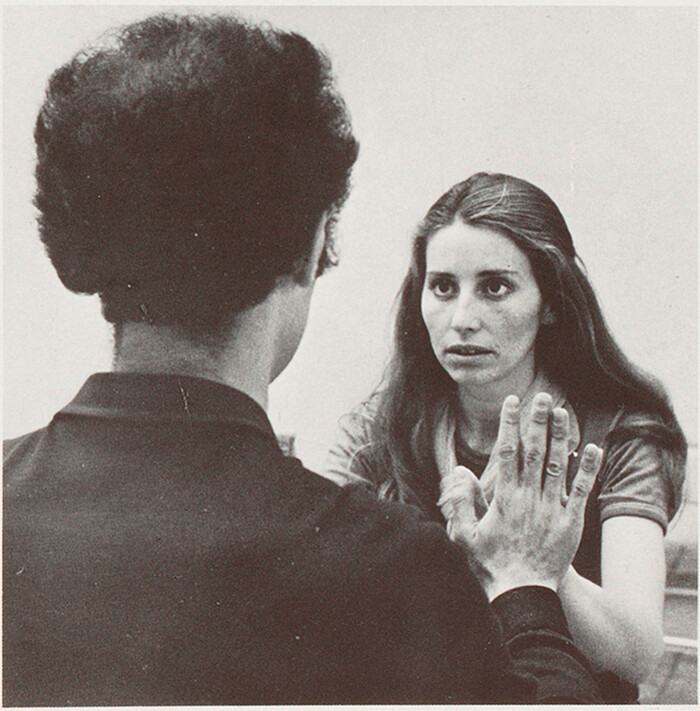

Yet, this moving-between-worlds becomes a curatorial end in itself as the hypertext of artistic poetics of almost a century of art history is presented here without formally living up to it. The classical canon of drawing, graphics, and painting to photography, the readymade, and performance are called upon here—while one is left to search in vain for the digital age in art. Moving images rather are an expression of conceptual experiences of the world (Allan Kaprow, Bas Jan Ader, Sigurdur Gudmundsson) and of early TV criticism (Ferdinand Kriwet) than of a being-in-the-world by means of new social media. It is this Biennial’s merit that Brazilian traditions in performance art (Hélio Oitica, Lygia Clark), which the 29th iteration had adopted, are now embedded into a global perspective offered up by artists such as Franz Erhard Walther, Simone Forti, or Jiří Kovanda, who, for their part, dealt with the body as a social-artistic medium in varied contexts (such as in post-revolutionary Czechoslovakia after the Prague Spring 1968). Today, this tradition is upheld in the post-participatory art of Ricardo Basbaum, for example. It is Basbaum, who in Você gostaria de participar de uma experiência artística (Would you like to join an artistic experience) (1994–ongoing) abandoned the idea of utopian solutions in favor of a transformation of the problems by stating that “You always have to keep a problem open.” With Basbaum the artwork is no longer the play of bodies with each other, but the collision of different materialities in the collective. Conceived as “community media,” the artistic radio station Mobil Radio (Knut Aufermann, Sarah Washington) created a transitory place for experimental music and discussion housed in a small pavilion within the greater Biennial Pavilion 3. For the first time, the Biennial invited 11 artists to exhibit in other places throughout the city, such as the Museo de Arte de São Paulo (Jutta Koether) or Estação da Luz (Charlotte Posenenske).

For the first time, August Sander’s photographic encyclopedia Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century) (1911–1952) is being shown in Brazil. Sander divided his portraits into 7 categories: the farmer, the craftsman, the woman, the classes, the artist, the big city, and the last human. With this survey, Sander, as part of the Cologne Progressives, marks out the longing for an avant-garde language of the prototypical. And yet his portraits can be read against the background of the emerging socialist workers’ movement of the Weimar Republic as well. Other large photographic series by Horst Ademeit or Alair Gomez not only confirm the principle of serialism, but also the desire for formal typologies. Very much in opposition to such categorical thoughts are the over 8500 photographs taken by the Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh, whose one-year performance consisted of taking a picture of himself every hour. The line of seriality, though, was continued with the portraits of the Peruvian descendants of Austrian and German immigrants, for example. These images by the young Peruvian artist Edi Hirose in their medium format seem old-fashioned and are formally quite similar to the portraits of Alfredo Cortina, presented publicly for the first time here. In the 1950s, Cortina belonged to the leading intellectuals of Venezuela. He photographed his wife in recurring landscapes, “staging” her body as such to engender a motif of artificial abstraction, morphing the natural landscape into a fiction. Indeed, I could carry on and tell you about more of the artists exhibited who worked in very similar ways, photography being one of the curators’ preferred mediums. In the sea of images, albeit, the artistic approach to photography in the context of its own time tended to fade away: from prototyping and contemporaneity, to staging and the conceptual documentation medium, all the way through to the archive of everyday life.

Flipping through the abundance of the photo albums of history bears a certain slowness and attention. In the age of digital platforms, these images quickly lose their poetic charm. What in Europe began with the cabinet of curiosities of the traveling, researching, and collecting subject, and later led to the development of the museum, here presents itself as the cabinet of curiosities of the artistic subject, such as in the intrinsic worlds of the well-known Brazilian artist Arthur Bispo do Rosário, whose works can be classified along the lines of Art Brut. The Biennial’s affinity for a kaleidoscope of artistic introspection and curatorial retrospection harmonizes and idealizes a cutaway view.

But if the curatorial motif focuses on myriad manifestations of radical artistic subjectivity, it loses itself in the multi-clause sentences of excessive prose. What began on the ground floor, with Deleuzian rhizome-like spreadings, ends on the 3rd floor in a museum-like retrospective. The exhibition misses out on the transfer: what was at many points a socially engaged survey does not equate “poeticity” (artistic activity) with “politicity” (social action), but rather releases the very potential of contradictions and antagonisms. In so doing, it confronts us with collective desire and action as opposing poetic modes of changing reality.

Brazil is one of the emerging BRIC countries, with a “racial and income inequality that has long characterized Brazil, a country with more people of African heritage than any nation outside of Africa. Despite strides over the last decade in lifting millions out of poverty, Brazil remains one of the world’s most unequal societies.” See here.

At least since the 29th edition of the Biennial, the nationalistic construct of the pavilion definitely disintegrated, therefore, a global variety of artists is given priority. Pérez-Oramas and his team focused on artists who are lesser known or who were never exhibited in Brazil before (22 of those are already dead). However, with the new generation represented by just 6 artists born after 1980, and a total of 23 women, a significant disproportion remains.

For the duration of the exhibition, the program can be listened to live here.