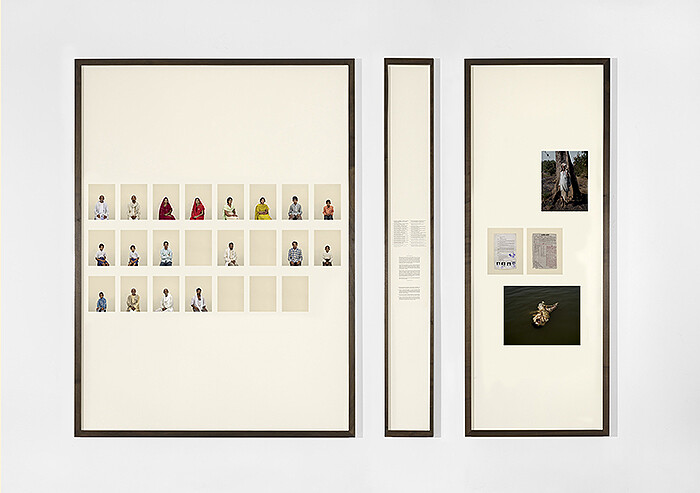

Repetition is never sameness. This is the first thought I had seeing Taryn Simon’s “A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII” (2008–11). An aesthetics of taxonomy, each chapter in the work is comprised of identical framed panels of varying width showing three types of information under glass: 1) serialized and numbered portrait photographs grouped together neatly in rows; 2) documentary text and a registry of names referring back to the portraits; and 3) staggered documentary photographs, which serve as narrative supplementation for the portraits and the text. The presentation is polished, clean, and simple with little fuss—much cleaner than the stories they have to tell.

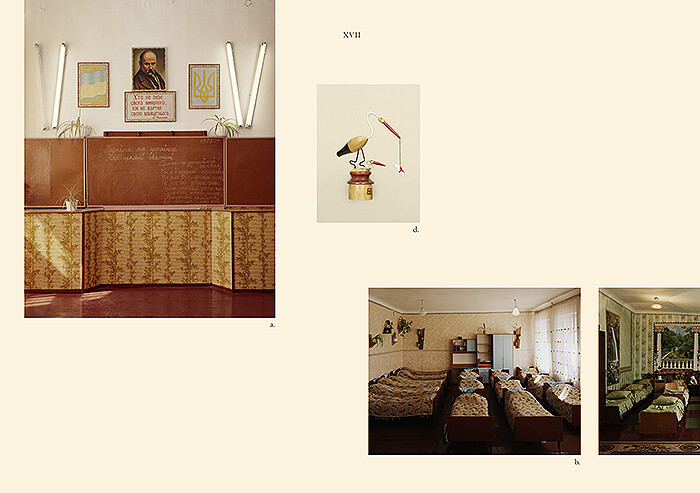

The work is the admirable result of research on a global scale, and each chapter documents sundry bloodlines and the circumstances surrounding their genealogy: a truncated family tree after the Bosnian genocide; the lineage of an official sent by the Zionist Organization to Palestine for settlement; a line up of mangled laboratory test rabbits not indigenous to Australia; the bloodlines of a family in the Druze religion based on strict inter-community reincarnation; a Kenyan doctor who gets paid in wives and cattle for his services; and the living-dead man himself, Shivdutt Yadav, whose status on the official land registry is that of deceased, like a tweaked retelling of Gogol’s Dead Souls in India. While geographically disparate, they each lay bare the ideological mechanisms—political, economic, religious, traditional—that inform and hold power over the lives that happen to find themselves born into their midst. The work is fascinating, often depressing, and wholly important.

The texts (placed on par with the images) provide the names and facts as directly and neutrally as seems possible, and it is up to the viewer to animate the portraits—all sitting with identical folded hands and backdrop—within their story-bloodlines. This even-handed neutrality, however, may pose a problem: there is too much left between the gaps. Simon lays bare but does not directly confront the ideological and historical forces attested to by her stoic sitters. Granted, inscribed in all these narratives are a multitude of delicate issues concerning colonialism and post-coloniality, political correctness and incorrectness, ideological fights that are not so much disagreements as différends (in Lyotard’s sense of disputes without the rules in place to decide them), or quite simply cultural traditions that cannot be translated and historical events that exceed representation. And yet I cannot help but feel that the work points to a zero degree of violence and call for compassion that exceeds all these delicate issues. For fear of seeming too knowing, the work seems to know more than what it wants to admit.

The viewer is free to interpret and becomes largely complicit with its meaning. It becomes difficult to separate what the work does to its viewer and what the interpreter does to the work. Choosing an entrance point is also up to chance. There is no reason to start with the first chapter. This invites a creative complicity, allowing the viewer to make the chapters communicate with each other either in affinity or difference. However, the seriality of these portraits lined up in exacting rows invites a darker form of complicity: a blurring effect of sameness. This is why the panel showing diseased test rabbits in Australia, one after the other in varying states of health behind glass cubes on pedestals—not unlike the taxonomic format of all the chapters themselves—became the key for the others (coupled with the image of the floating corpse whose bloated deterioration makes it look half human, half amphibian). Here we have the zero degree of power: pure disposability, the lack of uniqueness, and a purportedly “natural” site of experimentation and manipulation. And here is the difficult thought to confront: if we are honest with ourselves, there are any number of people out there who would think the same about many of the different ethnicities, classes, and regions represented by “A Living Man Declared Dead,” which they either believe, or have been taught to believe, are natural and unavoidable sites for misery and suffering. That they are on the wrong side of history, as that strange saying goes. Over there, but not here. The insidiousness of they all look alike. This is why I began with the Deleuzian thought that repetition is never sameness; repetition is neither generality, replication, nor equivalency. It is realizing the uniqueness of each iteration, a sensibility that is deeply ethical when dealing with life and its capacity to suffer anonymously.