Book blurbs often say things like “unputdownable” or “you want to start rereading the book as soon as you’ve finished it.” The film Gonda (2012) by Ursula Mayer (1970, born in Austria, lives and works in London) has this same compelling and luring quality. As soon as her 30-minute film is over, you want to watch it again. There’s so much there you feel you didn’t quite get. The flow of images is seductive and in combination with the voice-over, the movie is sometimes stirring and exciting, sometimes soothing and calming. And somehow nothing makes sense if you approach the film rationally. There’s a certain desperation, even panic to some of the things the female voice says: “No, it’s not mine. I don’t understand how it ended up in my basket” or “It’s just that I don’t like to be touched” or stronger even, “My death would have nothing to offer me.” Is she a frigid kleptomaniac on the verge of suicide?

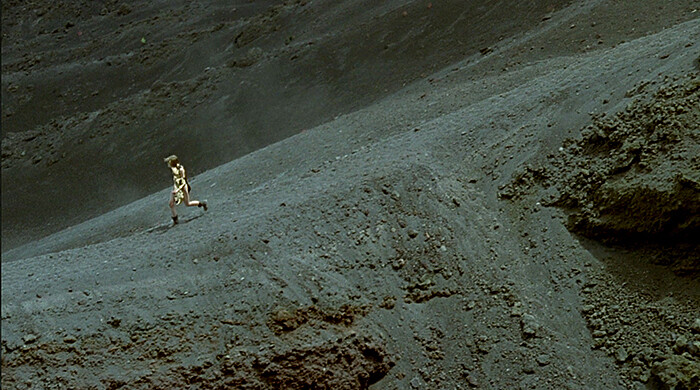

Gonda starts with a tall, skinny woman running over the hills: not pastoral, lush, green hills but rather volcano-like, post-apocalyptic, dusty hills. Then a jump shot to an abstract image of colored stripes, and then an Egyptian cat figurine, then back to the colors. The voice-over says, befuddlingly, “Oh, and the matches.” This pattern and flow of images continues, with the lonely running woman oscillating between Mad Max-like qualities and those of a Greek goddess. Sometimes the sequences of objects change so rapidly, flashing by so fast that you’re unsure of what you saw. A golden lighter? A sado-masochist leather cap? This flow is interrupted frequently by the words “comma” or “full stop.”

There’s a scene or two taking place in a cave with the running woman now sitting on a sofa while four specters, ghosts who disappear and dissolve into the walls of the cave, hover around her. Mike Sperlinger once said that Mayer’s characters are uncertain whether they are the dreamer or the dream—which is the case in Gonda too. In these cave scenes as well as in fashion shoot-style scenes (mocking the conventions of the Benetton or Hilfiger group portrait), we see that the five characters, lanky and elegant as they are, all defy gender.

Gonda is a kaleidoscopic movie, a mix and play with genres, a collage that both confuses and seduces. Mayer’s work is informed by new wave cinema and a modernist visual language—it challenges, investigates, and upturns the promises of cinema. But more than deconstructing the cinematic narrative and visual space, she also takes on dominant imagery of female beauty and identity by referencing fashion photography, commercial publicity, and working with fashion models.

Her film projects often start with a fascination for an older movie or text. In 2010, she took on the myth of Medea for her Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight, for example. For Gonda, the reference is the play “Ideal” (1934) written by the contentious writer and popular philosopher Ayn Rand (1905–1982). Some of her writings were very successful, but “Ideal” remained largely in the dark. “Ideal” tells the story of a movie star, Kay Gonda, who, unsatisfied and unfulfilled with her success, fakes a murder to test which of her fans will risk his life to protect her. This egocentric plot is very much in line with her “Objectivism,” a philosophy that proposed that the moral purpose of life was the pursuit of one’s own happiness: the only social system sustaining this pursuit, of course, was laissez-faire capitalism; an individualistic and non-altruistic philosophy.

Maria Fusco’s script for Gonda is based on sessions in which a variety of people reworked the material of “Ideal.” The text has autonomous qualities and functions, in the words of Mayer, on a meta-level in relation to the film. The voice of the Hollywood movie star Gonda that Rand created is deconstructed in Mayer’s Gonda where five different characters tell her story. The principal interpreter of Gonda is the woman running over the hills, played by Dutch transgender model Valentijn de Hingh. De Hingh tells the audience at the opening that the philosophical, scholastic, and open-ended script was what attracted her to the project. During Performa 11, Mayer showed an edited version of the movie and De Hingh performed the text live in front of the screen. The connection between performance and film is very close in the work of Mayer, often starting from one medium and moving towards the other.

In the front room of the gallery, Mayer also shows stones and gems that feature in the film. Placed on and under the glass of a small table, they are beautifully displayed, as mesmerizing as the film itself. Seeing them gives you a little start: offering up proof of a parallel Real, and evidence, so to speak, of Mayer’s cinematic universe.