Allan Sekula’s exhibition “Polonia and …” opens with a new piece, Europa (2011). Hung on a dark pink wall, Europa shows a man trying to sleep on a long narrow baseboard heater at the foot of a glass wall in Charles de Gaulle airport. A difficult balancing act, three of his limbs tentatively rest on a slightly higher cable railing and a low metal barrier that protects the heater from being bumped by luggage carts. Stemming from a desperate search for warmth and constrained by airport architectural details, his bodily posture uncannily resembles the pose of Titian’s Europa (in The Rape of Europa, 1562) being carried off by Zeus disguised as a bull. Rather than replicating the latter’s dynamic diagonal composition, this Europa lies as horizontally within the picture plane as does Walker Evan’s sleeper-cum-unemployed-drifter on South Street in his American Photographs. Indeed, instead of being transported by a divine force, Sekula’s Europa is paralyzed by economic forces. Nothing is less certain about the open market of today’s European Union than its promise of mobility.

One wouldn’t delve into such a reading of this single image if it weren’t for its title and the fourteen photographs and two quotes—selected from the project Polonia and Other Fables (2007–2009)—also on view here, which were originally presented in 2009–2010 by both the Renaissance Society in Chicago and the Zachęta National Gallery in Warsaw. But the titles and text booklet are missing from the current presentation at Galerie Michel Rein, and it’s rather unfortunate as Sekula focuses on subjects that can neither be captured by photography nor by words alone. The strength of Sekula’s art lies in the fact that nobody uses photography and text as he so brilliantly does. And this combination is what allows you to even begin to put parts of the puzzle together. Sizing up Chicago’s reputation as the city with the most Poles outside of Poland, Sekula gives us his take on what Poland and Polishness means for Americans of Polish descent—Sekula himself being a third-generation Polish American—and for Poles in Poland, in the face of America’s burly presence since their embrace of capitalism in 1990. True to his atypical approach to documentary photography and conceptual art, Sekula takes his own family history, as he did with his 1973 project Aerospace Folktales, as a starting point to chart larger ideological and social forces at work.

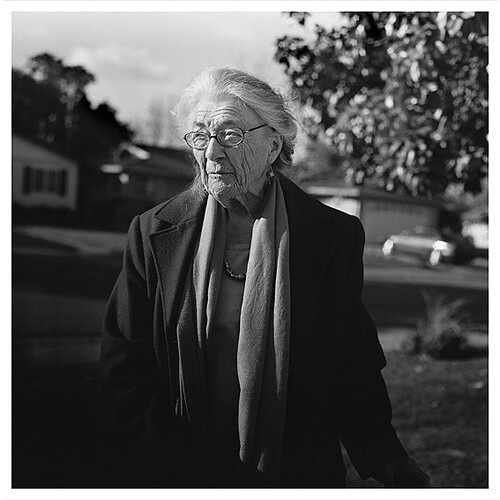

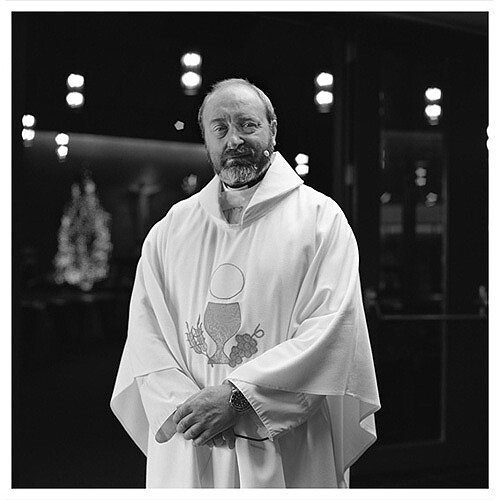

Europa is flanked by two pictures taken in Sacramento in 2008: on the wall to the right is a photograph of Father Andrzej, the priest who gave last rights to the artist’s father, and facing the priest, almost like a contact print facing a negative, is a portrait of the artist’s widowed mother. Further in the exhibition, however, a photograph destabilizes the Sekulas’ presumably solid Roman Catholic background: a picture from 1979 of the artist’s father holding a list of people who share his surname. Two of them are rabbis.

It was Sekula’s paternal grandfather, a blacksmith, who emigrated from Poland to the US. Sekula made the reverse journey in July 2009 to his grandfather’s native region and scouted out a traditional blacksmith’s shed. The photographs of a sickle being hammered out on an anvil and of a wooden door with carved outlines of the tools forged by the blacksmith form a vivid image of the bygone communist era.

Other pictures taken that summer include a Polish Air Force pilot getting ready to fly a Lockheed Martin F-16; a farmer threshing grass at an abandoned airport used by the CIA for transporting terrorism suspects; and the no-entry sign of a CIA black site, a secret prison where the aforementioned suspects are interrogated. Such trade-offs for debt forgiveness may be costing Poland more than it thought. Fittingly, these photographs are preceded by a wall text, a quote from Alfred Jarry’s 1896 preface to the premiere of “Ubu Roi”: “As to the action which is about to begin, it takes place in Poland, that is to say, nowhere.”

We never see the blacksmith but we do see a portrait of his heirs. His daughter’s head is cut off, but she is represented by her t-shirt with wings (of the Polish white eagle?) and her arms tenderly present her two daughters, the youngest of which presents a boxed Barbie doll. Another image of a generation to come can be found in a photograph of young woman at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Sporting a dowdy electric blue trader’s jacket, this futures trader by day and art student by night stands against a background of harsh colored lights and a paper-strewn floor.

The last picture in the exhibition shows that the outer face of Warsaw is vacuum-packed in advertising. The vinyl curtain about to drop on a massive façade is an ad for Era, one of Poland’s biggest mobile phone network operators (rebranded last year as T-Mobile). In front is a low circular building housing the PKO Bank Polski, which is fully wrapped in an advertisement for loans. In the missing booklet, Sekula’s concise comment on these vinyl ads covering the city is: “Body bags for all.” Summoning up the precarious living conditions that are becoming increasingly widespread in Europe, this final image comes full circle with the first.