There is something immensely gratifying about seeing an artist produce a roomful of artworks out of meticulously collected miscellaneous receipts, letters, forms, and paper ephemera from daily life. Perhaps this is due to the familiarity of the materials, or the fact that most of us take comfort in knowing that we lack the pathological tendencies that have led to such scrupulously hoarding, selecting, and organizing of all those original items in the first place. In Hong Hao’s latest undertaking “As It Is,” the obsessive impulse towards collecting is tempered by yet another—the urge to copy. Along with collecting, Hong has undertaken the immense task of tracing each miniscule word and letter, stroke by stroke in pencil on the reverse side of the paper. Copying is familiar territory for the artist, earlier bodies of works having involved traced magazine pages onto blank pieces of paper and self-produced fake biennial catalogues; one can see the links also to an earlier work called Invitation (1997), in which he and co-collaborator Yan Lei famously mimicked a documenta X invitation letter and sent it around to Chinese artists under false pretenses. But if those works edge towards the satirical, “As It Is” adheres to a more formalistic rigor. Here attention is paid exclusively to abstracting the physical surfaces of things, an interest that began with him previously using a flatbed scanner to scan the surfaces of assorted objects and produce inventory-like photographic montages but which has now consciously shed any mechanical or digital component in favor of the unswerving presence of the hand.

In Hong Hao’s hands, a flat piece of paper is easily transformed into a three-dimensional material object. This is in part achieved through the show’s mixture of collected historical documents—be it handwritten letters and papers from the Cultural Revolution period and earlier, or thick pads of unused miscellaneous forms, post-it notes, and the assorted crumpled taxi receipt or visa form culled from his own personal stash. Floating in box frames, the physicality of these papers becomes inescapable and in certain works the relationship between objecthood and flatness is delightfully obscured. Take for example the “Inside-Xin Yi” series (2011) in which Hong Hao outlines various household objects, scrawling around their base with a pen. These irregular shapes adorn square pads of colorless paper which are then mounted upon aluminum backing boards in random order, yielding an effect whereby the papers themselves take on an extra dimensionality while the objects themselves are reduced to flat outlines.

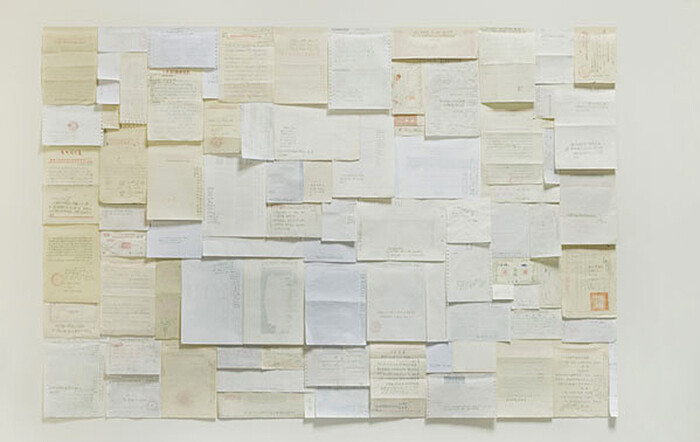

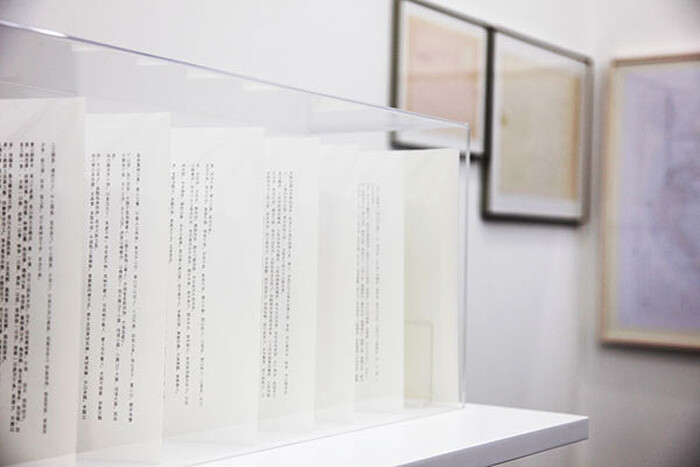

Other pieces in “As It Is” adhere more closely to the residues of a textual past. 100 Names in History (2011) contains sheaths of papers hung in a cascading fashion with their blank sides facing outward, each adorned with cryptic notes in different handwriting. The snippets of text scribbled in the margins of historic books by key political figures such as Zhou Enlai or Mao Zedong (downloaded by the artist from the web) have here been transferred onto a smattering of certificates, forms, and letters through Hong’s own hand. Fitting around the margins, Hong has carefully traced the different annotations, forming juxtapositions between the handwritten commentary and the contents of the original document. Occupying one corner of the smaller gallery is curious pairing: a settlement statement recording the artist’s stock market transactions from 2005, and a horizontally framed printout of Lao Zi’s famed philosophical treatise Tao Te Ching, both painstakingly copied by hand in reverse.

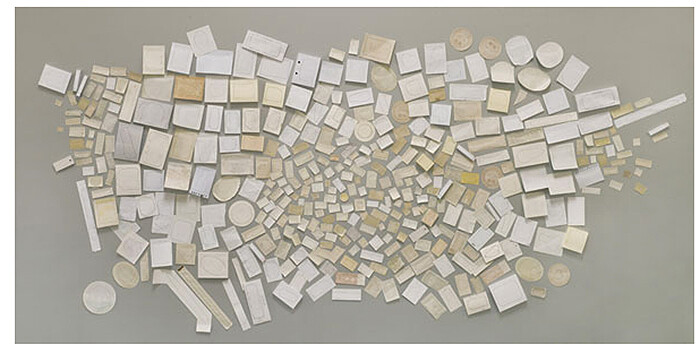

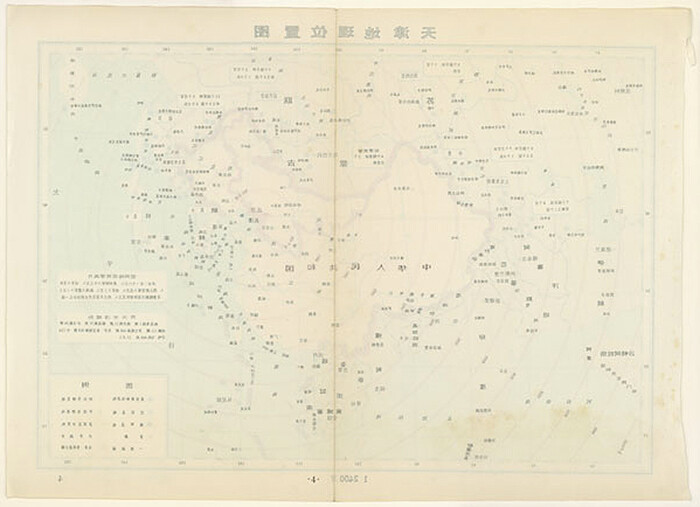

The exhibition’s undeniable centerpiece is Reborn (2011), a series of sixty-six printed and handwritten letters, notes, forms, deposit slips, and sales receipts mounted into different frames that spill over an entire wall. As the title indicates, Hong’s superimposed scribing on the reverse in pencil invests these used documents with new life: a rebirth signaled not only by the presence of human labor but by the merging of opposing qualities—real and copy, mechanical and manual, interior and exterior, personal and political, subjective and objective—into one cohesive whole. Whether it entails dragging a pen around a pencil-cup holder or outlining block characters on the back of a poster, “As It Is” reveals Hong’s roots as a printmaker, a practice whereby words, lines, and logos are seen as objects that can be isolated and lifted off or moved around the page. In the telltale work Reborn-Location Plan (2011), Hong flips over a map of China and every tiny bit of text is carefully traced over by hand, skipping all lines, borders, topographic, and geographic indicators. Not accidentally, we are left with a vision of a utopian world in which messy ties to social and political structures and institutions are mindfully absent.