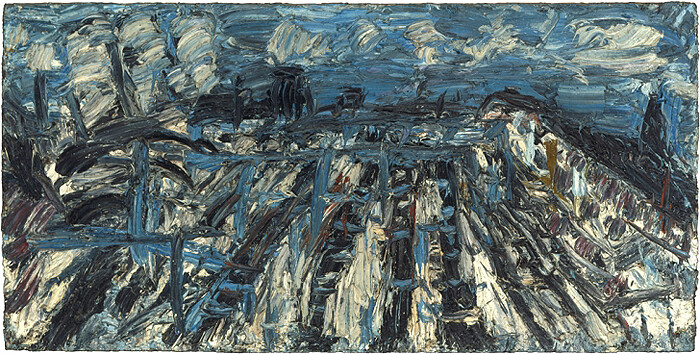

Willesden Junction, London, is not a particularly pretty place. It wasn’t in 1966, when Leon Kossoff painted Willesden Junction, Summer No. 1, and it’s not now. Overwhelmingly brown—a sprawling intersection of converging train tracks into a vast expanse of metal, rust, stones, and dirt—it is industrial and unlovely. Kossoff, however, his brush loaded with paint, rendered this place strangely beautiful and thick with optimism. The impasto has the tactile qualities of physical handling which gives a strong sense of the built environment, but it is also the screaming peacock blueness of the sky, on a warm summer’s day, which the artist has rendered as a physical presence too. Surprising blue dashes and stripes come down from the sky to mingle with the mess of drab blacks and browns below, a melange of trains, tracks, and platforms at the city’s fringe.

“The Mystery of Appearance” at Haunch of Venison, curated by Catherine Lampert, is a “conversational” exhibition between ten British post-war painters. The show is a subtle repositioning of what was in 1976—to some negative effect—proclaimed a “School of London,” by R.B. Kitaj, to corral together a set of painters who concentrated on figuration while minimalism and abstraction dominated critical attention. It became a rather useless term but, nonetheless, closely associated with particular painters—Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, Leon Kossoff, Frank Auerbach, David Hockney, Euan Uglow, and Michael Andrews, all of whom are included in this exhibition (though Kitaj himself, being American, is not). Lampert has pried the door of that “school” open, however, to provide entry to the influential artist (and Professor at Slade School of Art) William Coldstream from an earlier generation, and to usher in Pop via Richard Hamilton and Patrick Caulfield.

So here we are in postwar London—a bombed city bearing its wounds. “We gotta to get out of this place,” the Animals sang in 1965 in their anthem to a depressing town, “if it’s the last thing we ever do.” We enter the exhibition to find a room of paintings and drawings of the human figure. Freud’s Girl on a Turkish Sofa (1966) features a nude girl with dishwater blonde hair and dirty feet, positioned in such a way that her muscular rump dominates the canvas. Uglow’s Nude, Lady C (1959-60) is a bit brighter—a painting of a statuesque, redheaded woman sitting authoritatively on a white sofa; we can still see the artist’s pencil markings and cross-hatchings in this painting of patches, so that she appears like a collection of fleshy colors brought together for a moment, as though on a grid. This is taken to extremes in Auerbach’s Reclining Figure (1972): a dark expanse of navy blue and army green, on which thick, sticky streaks of tube-fresh yellows, pinks, and whites coalesce to suggest a human presence. Bacon’s Pope I – Study after Pope Innocent X by Velázquez (1951) with his elongated face, thick lips, and electric-chair-like throne genuinely feels like something encountered in a very claustrophobic, very bad dream.

The following gallery features several London landscapes, including the aforementioned Willesden Junction, which is hung near two starkly contrasting Auerbach paintings of Primrose Hill—in one, the trees and sky fuse into a drama of flashing golds, greens, and reds; and the other is a dark blonde landscape flecked with icy white and black of skeletal winter trees. Hamilton’s smooth photorealist painting, Mother and Child (1984-5), takes a rather different tack, obviously taken from a nostalgic family snap, depicting a toddler and a mother whose smile marks the point where the image has been cropped.

Lampert’s curatorial treatment of these painters—and the significant inclusion those associated with British Pop—can perhaps be understood by the way in which she has hung this exhibition within Haunch of Vension’s newly refurbished space. This becomes clearest as one ascends up the staircase and into the top-floor gallery, which has vaulted skylights at its center. Here, the paintings begin to take an aerial, more distanced view of their subjects: flatness rather than thick impasto begins to dominate. Hockney’s The Room Tarzana (1967) is a bright, even space, frozen and calm. The only agitation in the painting is implied by what has just taken place. (We see the flushed face of a boy, who lies facedown on the bed wearing only a t-shirt and a pair of socks.) Hamilton’s Whiteley Bay (1965) and Andrews’s painting of a reception in Norwich castle are both painted over photographs of crowds, flattening out the depth of field, while Caulfield adopted the simple, expressionless technique of the commercial sign painter to present objects and architectures that have a flattened out sense of time and space.

The catalogue makes clear that the artists viewed abstraction as an endgame. “We gotta to get out of this place, if it’s the last thing we ever do.” Hamilton states bleakly: “The first half of the century showed a move towards abstraction. You end up in a Malevich black square.” And Caulfield: “It was a sort of popularistic [sic] idea that the development of an artist in the twentieth century was that you started by doing some very good, tight drawings, and eventually some good figurative work, and then gradually becoming more abstract, until your work become more or less totally abstract, rather like Mondrian.” Both artists made work that was wilfully unfashionable—romantic images of flowers, girls, still lifes of bottles and jugs, that were “against the prevailing mood” and drew on a democratic language to do so— photography and advertising or sign painting and cartoon. Finding a way out of this place, they took an exit off the highway of abstraction, but also focused on the “drive” behind consumerism and popular culture: the belief that, “girl, there’s a better life, for me and you.”