Up to their knees, they’re identical: laced-up leather boots, pale socks, paler legs, shadow-strewn knees. Then difference begins. On the left, ruffles become a dress. On the right, checked shorts become a white shirt, become a soft bow tie knotted under a boyish face. Soft bangs falling over his forehead, he’s morose. Bows in her hair, she smiles. The little boy and girl holding hands might be twins. But the similitude does not end there. Hung near this difference-parsing, class-identifying photograph by August Sander—an elegant gelatin silver print didactically titled Middle-class Children (1925)—are Diane Arbus’s equally indelible and strangely edifying black-and-white photographic investigations of singles, couples, twins, and triplets made some four decades later. See her famous Teenage Couple on Hudson Street, NYC with their oddly mature faces and diminutive child bodies, or Triplets in Their Bedroom, N.J. (both 1963). The identical sisters are clothed as such: starched white shirts buttoned to the neck like fundamentalists, white headbands bisecting their dark, curly hair. The straight lines of their mouths mimic the line of their eyebrows, running parallel to the sad line of their eyes. Their faces conjure a perversion of Madeline’s famous rhyme: “In three straight lines they broke their bread and brushed their teeth and went to bed.”

In a 1960 letter Arbus noted, “Someone told me it is spring, but everyone today looked remarkable, just like out of August Sander pictures, so absolute and immutable down to the last button.” That she knew the German photographer’s work so well, and used a metaphor of dress to describe the social and seemingly psychological state of his subjects as an analogy to those who surrounded her, is not surprising. The two photographers plumbed similar themes and formal motifs in their trenchant and treacherous bodies of work, despite their separation by time and place. Station, class, and identity were dissected through dress, design, and environment. The weirdness of social stratification and familial classification was made clear in repeated images of twins, couples, and families in the crux of “good” society and on the very fringes of it. Thus, this well edited, cogent exhibition pairing the two artists at Galerie Edwynn Houk, the new Zurich branch of the estimable photography gallery in New York, shouldn’t have been surprising. Yet it was: the lasting power and startling frankness of Sander’s and Arbus’s oeuvres, dissecting and delineating twentieth-century social mores and postures, left me more than a little moved.

Houk’s exhibition resists chronological organization and instead favors formal parallels, perhaps even too much. Still, the breadth of societal change over the twentieth century asserts itself in the changing style and demeanor of Sander’s subjects. His earliest here is a female Confirmation Candidate (1911), her high-necked dark dress and long, plaited hair posited against a pastoral field. Her stiff, erect bearing stands in direct contrast to Sander’s Secretary at West German Radio, Cologne (1931), whose cropped hair, cigarette, handsome face, “oriental” dress, and seated, sloping body offers an assured vision of female modernity. So follows the evolution of Sander’s men, from the Prussian-groomed Police Officer (1925), whose enormous mustache is ready to take flight from his face, to the young, clean-shaven Soldier (1940), whose Nazi uniform and pith helmet frame a blank, seemingly benign face. Which brings us to the major unspoken theme, war, which figures everywhere in Sander’s portraits. His Germans are either living through the fallout of one or the horrific inception of the other. Every subject is implicated, becomes suspect: victim or perpetrator? Their stations—1920s-era artists or customs officers or bankers, 1930s-era innkeepers or court ushers—offer clues, suggest narratives. But their sharp photographic arrest also eventually arrests such thoughts. Their stasis—a product of the educational, encyclopedic tenor of Sander’s project—is weirdly complete.

If Sander’s photographs are haunted by the twentieth-century’s two world wars, Arbus’s images are shadowed, in turn, by the Vietnam War, most famously in Boy with a Straw Hat Waiting to March in a Pro-War Parade (1967), also on view here. The photograph is too familiar to provoke much at this point, yet the hawkish buttons the gawky youth with the big ears wears—”BOMB HANOI” and “SUPPORT OUR BOYS”—unsettle as ever. While this image stands in direct lineage to Sander’s work, with its subject front and center, his politics and station all over his face and dress, Arbus’s Two Friends on Bed, One Yawning (1965) shows her singularity, and the more casual and relaxed framing that prevailed in photography in the years after Sander’s time. I had never seen this photograph before. Two large windows, white with light, frame a young, heavy woman on a shadowed bed with a much younger boy stretched out next to her. In his hand, improbably, is a cigarette. His other arm reaches behind her, like a lover.

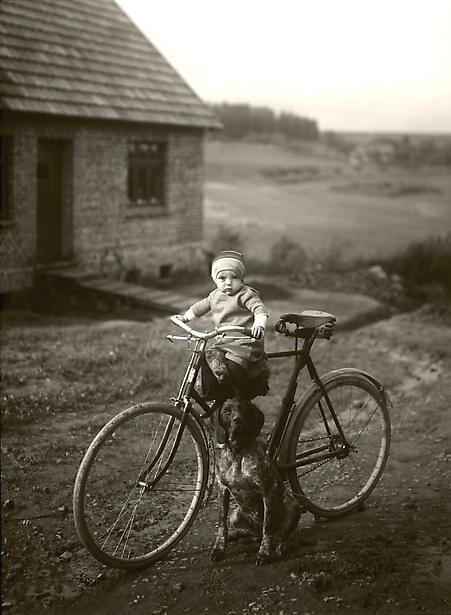

As elsewhere with Arbus, the coupling here is odd, is off, yet it is also exactly right. Not many of her images are included in this show, actually—for a trove of her work, see her Paris retrospective on view at the Jeu de Paume—but a few of Sander’s transmit Arbus’s innate weirdness. Take Forester’s Child, Westerwald (1931), in which an infant sits alone atop an adult bicycle, its tiny fists clenched around the handlebars. A thin hunting dog sits protectively at its feet. Both faces peer out alertly, disarming the viewer. But it is Sander’s Circus Artists (1926–32) that proves most prescient of both Arbus’s interests and images, and the social world that would gradually replace his. This is the only image here by Sander in which people of various color, class, gender, and perhaps religion, mix. A short-haired woman in a gaudy male military uniform leans confidently against a trailer, her bow mouth darkly rouged; a balding black man sits on a folding chair nearby, dressed in the same uniform. Circus ringmasters? Three dark-haired women in slinky robes sit around a phonograph, behind which a black woman eats and drinks something while staring straight at the camera. The group is comfortable, familial, if a little bleak—from the hardness of work and life, perhaps. What makes them unique outside of their profession is that they are a chosen family, as it were, instead of one inscribed by birth, color, and class. If their group suggests the end of the empire as Sander knew it, it also suggests the kind of family that would increasingly typify the ever-changing social world, one that both photographers located—on the fringes of artistic, impoverished society, where so many societal changes begin and are exemplified—so very early.