Cognitive dissonance. It’s a cliché by now, a toss-off term used to explain (or to keep from explaining) all sorts of contradictions, hypocrisies, moral and ethical failings, feats of self-loathing, etc. It has become a standard operating principle, the kernel of cynical reason, the delivery mechanism of mental detachment.

And we love it. We can’t get enough of it. Harmony is for hippie losers. Dissonance is complex, difficult, dangerous; it’s Heidegger in six-inch heels at a rifle range. It’s why we love family-guy politicians and the prostitutes they pay for dirty sex. It’s why we adore the billionaire record producers that rail against the 1% down at Occupy Wall Street. It’s why campus police (at UC Irvine) use pepper spray against peaceful student demonstrators, and why a customer (at Wal-Mart) uses pepper spray against her fellow Black-Friday shoppers. It’s why we believe in too-big-to-fail. And yes, it’s why we love Art Basel Miami Beach.

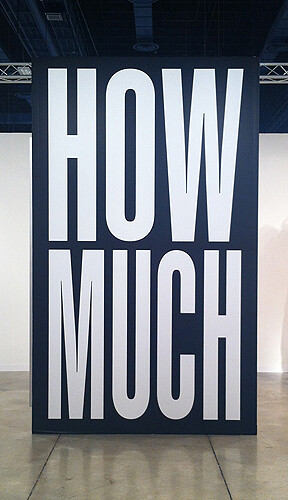

Where else could one find Mary Boone displaying huge black-and-white wall works by Barbara Kruger reading “HOW MUCH” and “BLEED US DRY” and “PLENTY SHOULD BE ENOUGH” directly across—literally facing—Dominique Levy and Bob Mnuchin’s solo extravaganza of Warhol’s early drawings (upwards of 100 of them) and wallpaper (a Ted Turner print no less)? Is this not like Xerxes whipping the sea—only it’s a sea flowing with money? And where else could you come across a melancholic installation of Ana Mendieta’s earth-bound Anima (1982) below a gunpowder silhouette (Untitled, 1980; at Gallery Lelong) and then ten steps later find yourself confronted with, if not walking across, an obdurate, expansive, Carl Andre floor piece (Steel Σ 15, 2010; at Alfonso Artiaco)? Who, I wonder, will have the courage to show these two artists together?

Emily Sundblad captures it all perfectly in her painting, “What Fails in Poison We’ll Provide in Steel” Pot-Purri Autumnal Advert for Energy and Noroit (2011; at Algus Greenspon), a confection of (unfinished) gestures and (fragmented) text, in which Sundblad declares to her viewers, in words that appear hastily applied, almost as an afterthought, “I have not fashioned this only for show and useless property”—everything hinges on that “only” doesn’t it? It’s worth noting that the first part of the title is apparently drawn from The Revenger’s Tragedy, a gruesome early seventeenth-century morality tale about bucking a corrupt and rotten court. The hero is brought low by his actions—it’s a tragedy, remember—but then so is the court.

But if the protest and political movements of 2011 recall for many the heady days of ’68 (when won’t they?), then the dealers this year, in good dissonant (or even dissident) fashion, have decided to capitalize on it too, but only with the best work. For example, Mitchell-Innes and Nash has mounted Martha Rosler’s multi-part photomontage work, Beauty Knows No Pain, or Body Beautiful (1966–72), on an exterior wall, where the many bare breasts and nude models that have been incongruously pasted to spreads of home interiors and magazine ads can do the work of drawing buyers’ attentions.

One of the better Art Kabinetts (by Two Palms)—the specialty section of the fair that singles out curatorial efforts on the part of the galleries—features a series of Mel Bochner’s old and new inquiries into photography. It begins with Misunderstandings (A Theory of Photography) (1967–1970), a series of photo-offset prints on note cards that bear aphorisms, by everyone from Mao Tse-Tung to the Encyclopedia Britannica, on the tricky business of mechanical reproduction and representation. The Encyclopedia explains “Photography Cannot Record Abstract Ideas,” which Bochner then took as the basis for Photography Cannot Record Abstract Ideas (1970), which records just that note card and so takes its revenge on the Britannica’s haughty claims. The final work, Photography Before the Age of Mechanical Reproductions (2011), reproduces again the 1970 print, though this time using six rare “pre-industrial” techniques. Only the sun was employed in printing, and apparently chickens were raised to lay the eggs for the albumen. This may be slow food for the art world, but it tastes great.

And then there is the side room at Blum & Poe’s booth that has been dedicated to a very elegant display of Mono-ha, the Japanese minimalist flowering that was coincident with America’s own but whose roots were more zen than empiricist, more natural than industrial—witness Katsuro Yoshida’s timber, rope, and stone arrangement (Cut-Off (hang), 1969/1986) or Nobuo Sekine’s Möbius-like Phase Drawings (1968)—and which was far less interested in certain navel-gazing problems of modernist painting. The room is actually a preview—and it’s not even an Art Kabinett!—of Blum & Poe’s upcoming late-February exhibition Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha. This is indeed the 60s without apology.

But these returns, to the problems of representation and presence, cannot but sound a bit out of key in the Convention Center. Their chords are, after all, a bit stretched, historically speaking, and they’re wound too tightly under the big top, they’re too pressurized, which, to be sure, is what allows them do their work, and do it so well. But being open to history threatens them too. They aren’t armored against the present. For that one needs marble, preferably Italian if the irony is to remain as richly veined as the rock. Vanessa Beecroft, no stranger to the politics of representation (and perhaps a progeny of Rosler’s?), has outfitted Lia Rumma’s booth with six quasi-classical fragments of female heads and bodies carved in Red Francia, Blue Sodalite, Lapus Lazuli, and other such properly named stones. Classicism, like gold, must be a safe haven.

Elmgreen and Dragset surely must think so. In what is without doubt the gayest booth at the fair (Galeria Helga de Alvear’s), the Danish collaborators have installed NEW BLOOD (2011), a large reclining Adonis receiving an I.V. drip of blood (to E&D’s credit, the sculpture is polyester resin, and the blood is fake; no “flight to quality” here). The sculpture is the centerpiece of “Amigos,” a fictional gay spa replete with locker room (LOCKER ROOM, 2011), a sauna with a copy of Yukio Mishima’s Forbidden Colors (1953), monogrammed towels (TOALLA, 2011), a pair of urinals with entwined plumbing (GAY MARRIAGE, 2010), and a waxwork figure face-down on a massage table (THE TOUCH, 2010) that shows just how much the artists owe to Robert Gober.

The classical attitude can be found again in Ragnar Kjartansson’s Song (2011; at i8 Gallery), a six-hour HD video of what must be Odyssian sirens enchanting no one in particular with their ethereal tones while reclining on a blue-satin clad circular bed that is situated, naturally, within a classical interior court.

Who is the most dissonant artist of all you ask? Who might be crowned king of fair this year? That would have to be John Miller. Not only can you find his work as the subject of two Art Kabinetts, but it is also on view, by my count, in no fewer than four different booths. And on top of this, the Rubells—never ones to shy away from the trappings of high dissonance—have given Miller an entire room in their aptly titled “American Exuberance” exhibition. To put it bluntly, his shit is everywhere.