“Our culture hero is not the artist or reformer, not the saint or scientist, but the entrepreneur. (Think of Steve Jobs, our new deity.) Autonomy, adventure, imagination: entrepreneurship comprehends all this and more for us. The characteristic art form of our age may be the business plan.” This cultural postulate is a passage pulled from the article titled “Generational Sell,” recently penned by William Deresiewicz for The New York Times.[1] Its overarching thrust suggests that today’s youth culture, including the Hipsters and the Millennials, are cozy with commerce: self-producing, self-publishing, self-managed, and self-promoting their identity. “The self today is an entrepreneurial self, a self that’s packaged to be sold,” claims Deresiewicz. Enter Rodney Graham’s new body of light boxes. These painstakingly detailed and meticulously pieced together digital tableaux exhibit Graham as an actor on stage in roles, albeit, out of place and time. Culled together from a commingling of his personal memories and found photographs, Graham’s glowing illustrations are soporific character studies in step with a photographic tradition that extends from Julia Margaret Cameron’s Victorian allegories to Cindy Sherman’s film stills in the late 1970s.

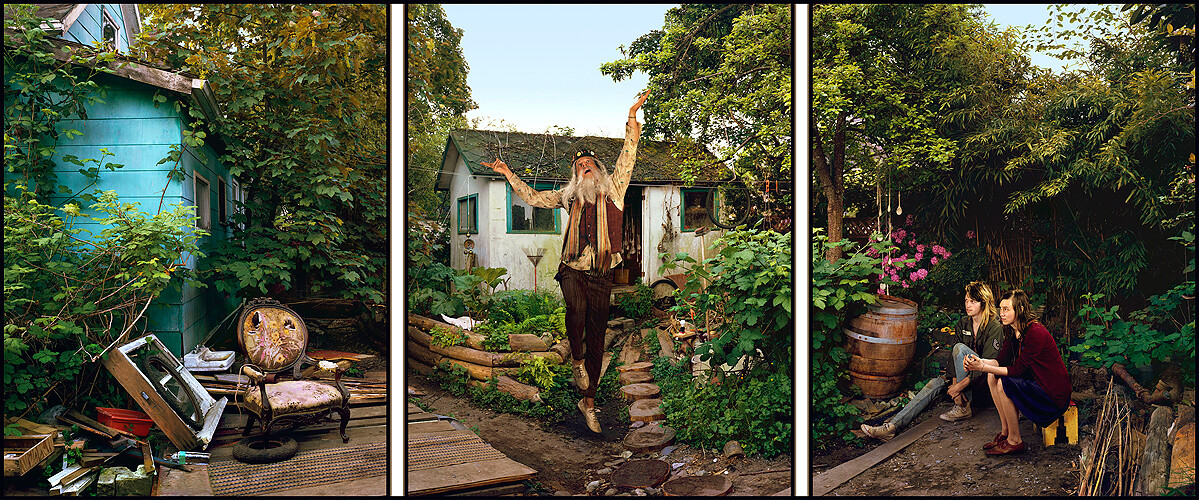

Nonetheless, Graham, a worldly-wise, middle-age man, is recognizable as he dons several roles in his compositions. At times, he takes on a central iconic character in both the Leaping Hermit (2011) and Betula Pendula ‘Fastigiata’ (Sous-Chef on Smoke Break) (2011). But in Small Basement Camera Shop circa 1937 (2011), he is simply a prop standing behind the counter next to a display of period cameras. And in The Avid Reader 1949 (2011), a monumental triptych, Graham plays the role of an extra to the picture’s main protagonist: a shuttered Woolworth five-and-dime store with its street windows neatly papered over with newspaper spreads. In a warm, nearly sepia-toned scene, a man in a deep blue suit stands in the shop’s entrance intensely reading the posted papers. The details yielded by this colossal light box reveal that the newspaper was printed in 1945 while the title of the work locates the setting in 1949 (the year of the artist’s birth), an example of the historical pliability Graham affords his photographic constructions.

His authentic itch to rework found imagery combined with an intellectual drive to reassess cultural tropes locates Graham’s personae-based photographic work in a historiographical field of investigation. Exploiting spectacular scale, these photographic renditions challenge the sublime qualities of the picture-making practices of his German contemporaries Struth and Gursky. Instead of originating new compositions, Graham builds on existing representations that wallow in reflexive, slow, humorous, and literary attitudes toward invention. Leaping Hermit, for instance, is a magnificent cliché. A bearded eccentric is suspended mid-air in an unkempt and overgrown cottage yard. The mossy vegetation, gray sky, and vernacular architecture situate this modern day hermitage in a sort of fictional Northwest community. The two young slackers hanging out in the Hermit’s yard gaze perplexingly at the hackneyed misfit. Perhaps it is because today’s youth “contains no element of rebellion, rejection or dissent—remarkably so, given that countercultural opposition would seem to be essential to the very idea of youth culture,” writes Deresiewicz in “Generational Sell.” Therefore, as entrepreneurial ideals take hold of creative and moral aspirations, the dramatis personae of Graham’s work become synonymous with self-branding and self-marketing. That said, Graham’s work is located, nonetheless, in a modern paradigm as an exercise in understanding representation within historical trajectories.

[1]Deresiewicz, William, “Generational Sell” The New York Times, November 12, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/13/opinion/sunday/the-entrepreneurial-generation.html?pagewanted=all