Black-and-white images of young androgynous women illustrate the introduction to Moyra Davey’s video Les Goddesses (2011). Wearing tight white t-shirts and cropped black hair, they stare directly into the lens. Davey speaks over the images in monotone, and introduces the female lead of the film, the protofeminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, as well as her children and her lovers. Various shots of the same four figures, together or paired in front of a white colorama, individually on turf, against a brick wall: the characters Davey tells us of become the young women that we see.

Davey’s new video is just over an hour long and is served in chapters. Title screens herald each section and footage alternates from close detail of photographs and books, static shots of Davey’s loft apartment, and shots from her windows. It’s unclear if she has just moved to the place. The apartment feels like a lonely Sunday afternoon. Quiet and contemplative, melancholic even. Bookshelves are half empty and frames packed in bubble-wrap.

Davey paces the apartment carrying a handheld recorder. One white headphone is held to her ear, the other lies dangling. She is determined and concentrated as she speaks, making sure she follows the recording. Unpaid bills are attached to the walls with masking tape; next to them is a drawing of a tree, roots like lank hair. Mary attempted suicide with laudanum in 1795 but was saved by Gilbert Imlay, the subject of her unrequited love. Her daughter Fanny used the same technique successfully at the age of 22; Davey’s son Barney was born two hundred years later.

Under the heading “Les Goddesses” we see only a photograph, no narration this time, of four figures dressed in glam-rock gear. May 22, 1976. The camera faces a mirror now: “How do you feel when you are with your son and your husband walks in?” I start to find I can piece together her apartment from the various shots and imagine her domestic life. Wollstonecraft died eleven days after the birth of her second child Mary (later Mary Shelley). High ceilings, airy, but the space feels claustrophobic; beyond are views over the water towers, rooftops, and rising steam. As children, the two daughters, Fanny and Mary, and the adopted Claire became known as Les Goddesses.

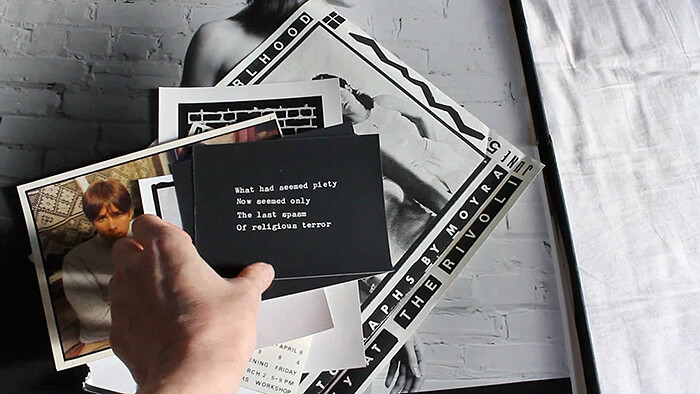

The room is flooded with sunlight. Davey sits on the floor of her bedroom leafing through prints. The same four women from earlier, tight white t-shirts, slim. They stare, bare-chested and free of inhibition. The camera studies their figures intimately; they must have been close to the photographer. One illustrates an invitation card—”Moyra Davey: A Catholic Girlhood.” These are figures from her past, but they blur with the lives of Mary, Fanny, and Claire. Davey paces in and out of shot, always repeating her own recorded words. Galleries make Barney sleepy. His ideal day would be spent watching planes taking off. Percy Shelley died in a boating accident at Lake Geneva. At times a metallic Moyra Davey from the recorder can be heard over her recital as she begins to slip. She becomes increasingly frustrated as she looses the train of her narrative. Subtitles correct her. “Erratum: Percy Shelley died in the Gulf of Spezia off the coast of Pisa.” To what extent everything we are told is accurate is quite unclear.

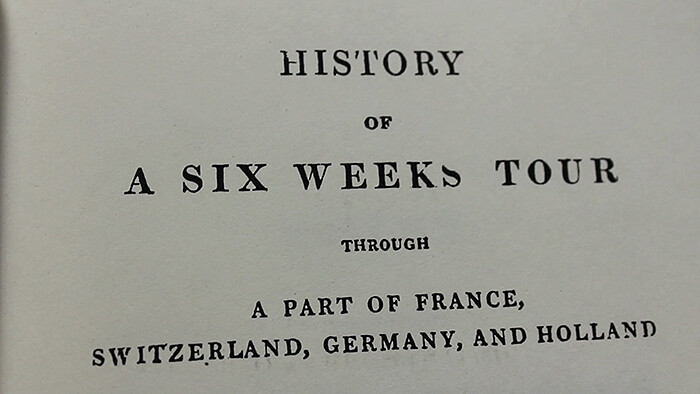

The narrative returns to itself, the making of the film, the motivation for specific shots. Whilst we hear the overlaid narrative, she takes books from shelves and blows the dust from their jackets: Mary Kelly, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton. Like Wollstonecraft, these are players in the inner space of Davey, a mental space we have been given an hour-long admittance. Small grimy spirals scatter out of the open window towards the air-conditioning unit of the building opposite. Images from Davey’s youth mingle with those of Wollstonecraft, her wider influences, anecdotes, historical incident, her domestic life, Davey herself. We watch her recite a recording on herself, by herself with a cold distance to this most intimate of subjects: her errors and anxiety show up as a false objectivity. We hear about Goethe’s close observations, about his ideas on the elasticity of air and space. Snow floats, hovers and falls hard.

Outside of the main gallery space there is a selection of prints folded and posted individually to the gallery. Each depicts a different individual, writing in the green-orange light of the crowded subway. It is a return to figuration for Davey, but in her depictions of empty scenes and domestic settings the figure is never far away. The same underground writers are introduced in the film’s coda, one after the other, looking at the page lost in concentration, oblivious. Exploring the gap between the thought, the written, and the communicated, they are photographs of the subliminal. It is a space “Les Goddesses” manages to recreate for the viewer. With precise observation, this psychological self-portrait is a series of clues with no conclusion.