Can an exhibition be too tight? Such is the question when experiencing the immersive world of “La Carte d’après Nature,” a group show curated by Thomas Demand currently on view at Mathew Marks, which debuted in late 2010 with a few variances at Nouveau Musée National de Monaco.

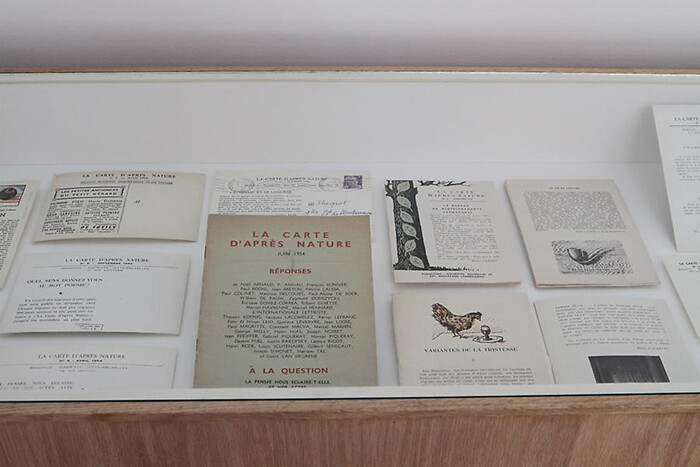

The exhibition itself takes both its name and its inspiration from a short-lived journal published by René Magritte in the late 1950s and early 60s. A quasi-retake on the exquisite corps, Magritte set in motion a correspondence game where picture postcards were mailed to friends so as to spur short replies in the form of associative thoughts, sketches, and clippings. These source materials, part found object, part commentary, were edited by Magritte into a pamphlet which overlapped streams of thought and mood. Building on this methodology, Demand instead looked to a trans-historical collection of artists and architects so he could create an exhibition in the form of a daisy-chain essay. The topic? Its main thrust is the “domestication of nature.” As such, many of the works focused on photographs of potted plants and gardens; however, each representation held a kind of fanged “surrealist” attitude.

If a surrealist take on the domestication of nature is here meant to convey the tension at the threshold between enlightened notions of the beautiful as something under control, i.e., a horse grazing in a fenced pasture, and the sublime as wild, i.e., a bucking bronco, the cool blast of the exhibition’s climate control (to offset the hot lick from a wet dog that is the high humidity of the New York summer) was one of the best introductions possible. Upon entering the gallery, a giant partition shields the sun, but it also hosts Martin Boyce’s Trough the Trees (I) (2011), a raw steel-framed irregular window punched into the wall. Within the context of the show, this work doubles as a kind of device affording many agendas. For one, the glass is covered in a blue gel, which aides the icy cool feel of the a/c and casts the exhibition into a kind of macabre crepuscular twilight in which the view teeters on the edge of the obscured and the revealed. Furthering this liminal state, the window is also a porthole from which to peek onto a reassembled model of the Canadian Pulp and Paper Pavilion from Expo ‘67, a building that resembles an abstract forest composed of pointy green pyramids. Construction photographs of the actual building are mounted next to this little forest-cum-tent ensemble, which stems from the firm of the architect William Kissiloff.

Next up is Drawing from a Floor Plan (2011), a work by Boyce in the form of an architectural plan. This map of a fictive space features a series of jagged angular walls cutting up a rectangular field into a labyrinthine suite of galleries within a gallery, which Demand uses as the floor plan for this nine-room exhibition—a major change from the Monaco edition. Upping the ante of this gambit, the visitor is presented with the other side of Through the Trees (I) and, with it, a reverse peep. Unveiling another one of its twisted boundary plays, the exhibition seems to tease out a notation of the peek-a-boo, which is not always all that reliable either.

The entire eastern wall of the gallery is covered ceiling to floor with Wallpaper II (2011), by Demand, his only work in the show. As its title suggests, Wallpaper II, is just that: an immense piece of wallpaper of a red draped theater-like curtain. On top hangs Magritte’s Parmi les bosquets legers (1965), an atmospheric oil on canvas whose eerily subdued silence of two mounds in dark consort is nicely complemented by the dramatic anticipation of Demand’s undrawn curtain. In order to find a way beyond the screen, one could slip through one of the passageways presented by the extruded walls of the Boyce layout. But wait? What happened to theme of domestic nature?

Easing into a den a little cozier than the great red wall is Demand’s first of many studies on photography (the artist’s own preferred medium). In this smaller gallery hangs a series of August Kotzsch’s mid-19th century albumen prints of lilacs, roses, and leaves, which look strange today, as their age and technique render unfamiliarity. Calmingly, their obvious return to the proposed theme is welcomed. Near by is Henrik Hakansson’s New York (2011), a field recording of ambient noise and chirping birds in the Rambles of Central Park, lulls us back to a contemplation of birds and bees over that of the overt hide-and-seek peeping-tom perversion. Dear prudence. We can now move on to another world, which of course riffs off the last in an oblique fashion.

This tangential walk through themes and variations is a highly scripted affair no matter where you turn though. Just like the hint dropped by Drawing for a Floor Plan, the exhibition gives way to its next, masculine Dom. Of the 75 works included in the show, over half of them are by the Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri. The exact reasons for such are slightly hermetic, but it is safe to assume that Demand simply looks to Ghirri as a mentor—maybe counter-intuitively, and more so than to Magritte. Ghirri’s postcard-esque tableaux certainly nod towards Magritte’s mailings and our alleged narrative, particularly in a set of overgrown vines and gardens on the precipice of turning wild, which smack of a restrained terror just beneath a banal front. Suppressing this wild undercurrent, Demand chose to hang these works in an exceeding regimental order: each are presented in strict horizontal bands which strip-stripe many of the walls in several of the galleries.

Various other plays on space, time, and reality are further advanced in the other galleries. Saâdane Afif’s Stratégie de l’inquiétude (Strategy of Anxiety) (1999), presents a table height topographic model of a mountainous landscape held up by saddle horses in plan view. In turn, this “anxiety” is heightened as a set of Ghirri’s images of Alpine landscapes, that may in fact be carefully framed photographs of models or representations thereof, begs the question: is “the natural” an artificially constructed support? Likewise, Boyce returns with another blue window embedded deeper in the gallery maze, while Chris Garafolo’s natural history museum-like cabinet of delicate porcelain figurines of imagined plants exposes yet again a quaintly bizarre idealization. After returning twice again to two different Magritte paintings, the show culminates in one of its three filmic works: an installation and film by Rodney Graham entitled Phonokinetoscope (2001/2). Here, the artist has separated the audio track from the visual as the projector screens a silent film of the artist presumably taking a break from a bike ride in a park, while a turntable plays a psychedelic musical score that evidences not an actual record of the events but instead proffers a subjective retelling of it sonically. This dissociative maneuver of separating sight and sound tells another story as the bike trip depicted was performed under the influence of LSD—possibly a passing reference to Albert Hoffman’s self-test of the chemical on his famous “bicycle day.”

Taken as a whole, the show seems to posit photography and painting as possibly against architecture (and, with it, sculpture and installation), film, and sound. Given the maze-like floor plan of the exhibition, where each work and its position relies on a memory map of the space so as to read the scripting of the procession, the introjection of the static world of photography and painting as landmarks is a curious one. What could Demand being saying here? That architecture, film, and music rely on time to shape their abstractions, while photography creates itself through the very act of abstracting time? Whatever the answer to this riddle may be, it lies within a riddling architectural conceit and its obfuscating rules. And although this kaleidoscopic environment does produce massive sensorial effect, its total observance to Demand’s not-so-hidden order comes off in the end as affect—like a dry instructional attempt at an erotic striptease where no one gets naked. Tricky enough though, this too points to a form of domestication, and the exhibition begins to take on the semblance not of a show, but as an essay in interior decorating.