“The Lifestyle Press,” a group exhibition curated by Gil Blank, opened with its ambitions foreclosed. Just days before, Blank had been informed that the publication which was to accompany the show, a mock junk-mail circular with coupons that could be used toward the purchase of artworks, would not be printed under threat of legal action. Apparently, when the UPC numbers on the coupons—expired in some cases, fudged in others—failed to check out, the printer and distributor refused to go forward with publication. As a framed letter hanging in the front gallery explained, producing the circular would have made all parties involved liable to suit. At the urging of Cherry and Martin’s lawyer, Blank abandoned his pursuit of circulating the circular, and instead resolved to present the cancelled proofs in the gallery.

A cynic might call this a confirmation of the inevitable: is it any surprise that the circulars, which were to have been inserted into the Los Angeles Times and sold at a low cost, ended up back in the embrace of gallery walls? And wasn’t their gamble—that someone could coupon-clip his/her way into collecting art—a little too improbable to be of much critical consequence? But cynicism distracts from what might account for the letdown in the first place. That no one involved anticipated what, in retrospect, seems baldly unlawful speaks to the art world’s abiding and often illusory class identifications, which make coupon circulars seem like appropriable forms rather than, say, regulated and monetized certificates.

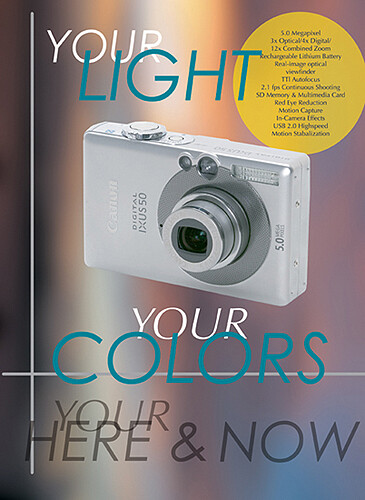

Ironically, those are the very class associations foregrounded by the (real) lifestyle press, whose glossy spreads promote visions, in the curator’s words, of “the good life as a perpetual buy-in.” To reflect on this theme, Blank invited four artists whose activities shuttle between commercial and fine art contexts. The exhibition’s almost aggressively uninspired act of curating—one artist per wall—either wittily or unwittingly indicated that the gallery is merely a secondary context for this kind of imagery, and for the commercial gains of this kind of artist. Sam Lewitt’s Darkness Elsewhere (2007) locates itself in the lifestyle press’s primary context with four offset prints, humbly stuck to the wall, which meticulously mime magazine pages. Two sets of subtly varied photographs of a sunset, captioned by light meter readings and hours of the evening, sandwich a camera advertisement and a short narrative about capturing a lunar eclipse. Transcendent experience is lassoed by a standard gadget that pledges to deliver, as the ad says, “Your Light, Your Colors, Your Here & Now”: the subtext of any ad that promises access to your life, provided you buy into theirs.

Other romantic views arise in a sequence of photographs by Hannah Whitaker. Shifting among vistas of a Coloradan silver mine, a silver gelatin print of an Edward Weston-esque nude and a pair of mostly naked ladies wearing silver-rush accessories, Whitaker’s work gestures toward some of the precious metal’s associations. But though it fails to live up to any rigorous historical materialism, it does suggest a range of desires and assets, and the audiences that may or may not share them. The impeccably framed photographs do a swell job of flattening those distinctions under the logic of the photo suite. It’s an insightful move, although one might wish that images of naked women didn’t have to serve as its hoist.

Noah Sheldon’s Miami, Miami (2010) also channels the photo spread, depicting the city in images fit for a travel editorial. Like Whitaker, Sheldon includes a couple shots that worry the seamless city image—workers in a field, a startling night shot of foliage—yet these photos don’t challenge so much as prove the subsuming force of the lifestyle genre, in which anything departing from the editorial line merely reads as local color.

Roe Ethridge engages this totalizing effect, too, although his work channels a very different lifestyle: the middle-class American dream, congealed in piecrusts and laundry detergent. Still lifes in the idiom of circulars (bananas and daisies around Tide; fake berries and sprigs of wheat around the Ready Crust) are re-photographed against a garden fence before a cerulean backdrop. Twice mediated, they highlight this exhibition’s inapt collapse of Dwell and the coupon blast—like Ethridge’s studio shots, everything seems to fit seamlessly, but only by virtue of an arrant superficiality that soon gives itself away—as well as its efforts to create distance between these worlds by ignoring the divergence in the way their images function. That ignorance is sinister… and revealing. It remains an indicator of an art world that, regardless of the economic realities and backgrounds of its members, fiercely allies itself with the class codes of the “lifestyle press.” Even when that results in a blind spot so large it blots out most of a curatorial premise