One hears a lot of grumbling about Art Basel. Or maybe it’s just the leftist company I keep. Still, I was surprised to meet more than a few people who had travelled all the way to Basel for reasons peripherally related to the fair but who had refused to step foot in it, according to the misguided “principle” that blinding oneself to the commerce of art is proof of genuine anti-capitalist credentials. Whatever happened to “know thine enemy”? And is the fair really the enemy? Well, historical materialists like me don’t believe in fairy tales and—guess what?—ignoring the art market does not make it go away. My choreographed wander through the behemoth Hall 2 was exhausting, terribly instructive and, in some cases, more aesthetically gratifying than many of the exhibitions I’ve recently seen in non-profit institutions.

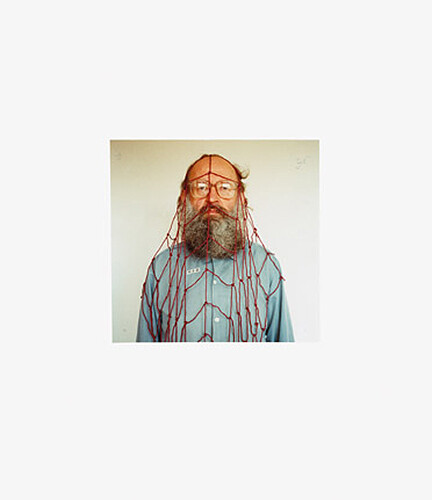

Worth the trip alone: Isabella Bortolozzi’s stand, especially Carol Rama’s Movimento e Immobilita’ di Birnam (1977) with its limp bouquet of flaccid black rubber bicycle tire tubes, visually spare yet enticing. In an entirely different register, at Air de Paris, I didn’t know how to quit Dorothy Iannone’s Brokeback Mountain (2010), a brightly painted freestanding object, like a miniature altar, featuring portraits of the characters from Ang Lee’s 2005 film locked in a tender embrace. Galerie Neu revealed the cross-fertilizing coherence of the artists it represents with works by Claire Fontaine, Manfred Pernice, Kitty Kraus, Tom Burr, among others, while gb agency invited introspection with a group show centered on the self-portrait. Julius Koller’s U.F.O-Nautes J.K. (1983–2002), a selection of the yearly portraits the artist made of himself wearing or holding props ranging from a tennis racket to a dinner plate, and Ryan Gander’s glowing red head in his tiny thermal Portrait of the Artist Conceiving This Title (2010) poked fun at the genre. At least here, on my maiden voyage to Art Basel, or The Art, as my Swiss friends refer to it, I felt no pressure to conceal or to justify my admittedly rather eclectic tastes in art—I could just point and gape.

After a couple of hours of hobnobbing with the well-heeled glitterarti, I headed over to the alternative space New Jerseyy and waded through the throngs of people clustered on a sidewalk littered with beer cans and triangular plastic sandwich sleeves from the gas station across the street in order to catch Kim Seob Boninsegni’s performance We Are Coming Through in Waves. I parked myself in what I thought would be a good spot, while clutching a piece of paper one of the performers asked me to hold. At some point, she told me, she would come and fetch it and read the text written on it aloud. Given the size of the crowd New Jerseyy was obviously THE place to be, but not the ideal setting for viewing this performance. The only thing coming through in waves were more people and, in the end, glued to my tiny patch of pavement, I thought the rest of that line the artist cites from Pink Floyd—”your lips move but I cannot hear what you’re saying”—would have been a more appropriate title. After that I decided to limit my performance-going to Carsten Nicolai’s Alva Noto at the Kopfbau, a throbbing and pulsating full-body experience of flashing fragments of visual stimuli and sound that literally had my heart racing and my seated bum bouncing off the floor.

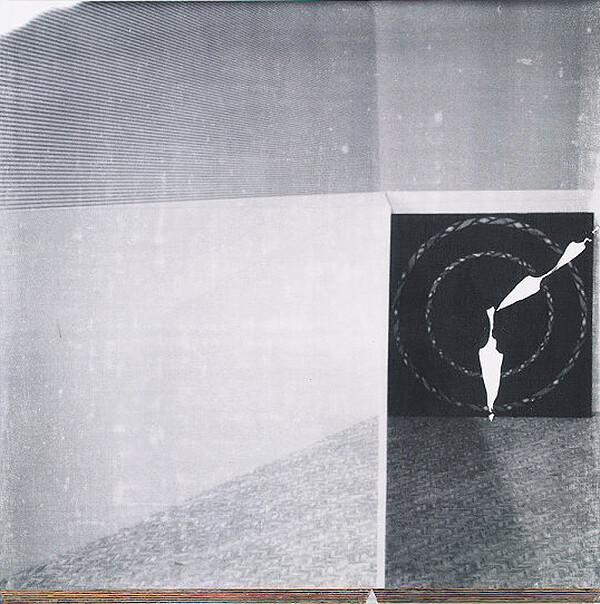

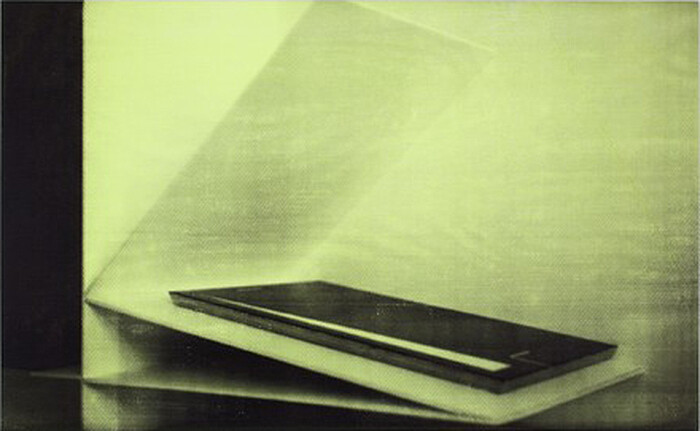

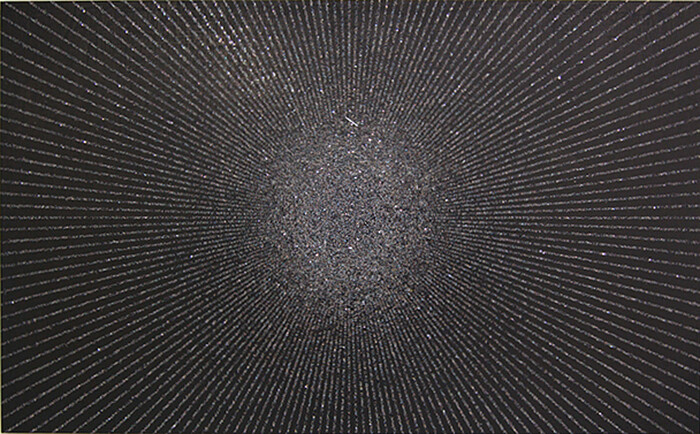

Whereas I was more or less prepared to deal with the expected crowds at Art Basel, I was truly done in by the juggernaut at the opening of R.H. Quaytman’s solo exhibition Spine, Chapter 20, at the Kunsthalle Basel, so I rushed through and hightailed it out of there to seek respite (at the Messeplatz, of all places). Early the next day, I was able to savor Quaytman’s paintings in near solitude. A quasi-retrospective, the entire set of works here (since 2001), grouped into “chapters,” were conceived to function like the index of a book, with the purpose-built walls of the Kunsthalle’s main gallery standing in for its pages. Quaytman’s fluid negotiation of the contrasting visual effects obtained with blocked areas of opaque paint (Quire, Chapter 14, (2009)), semi-transparent photographic silkscreen (Lodz Poem, Chapter 2, (2001–2004)) and diamond dust (Silberkuppe, Chapter 17, (2010)) on the thick plywood supports she favors over canvas, forcefully counteracts the conventions that abstract painting is all about surface and that perspective is all about three-dimensional illusion. Those seemingly contradictory aesthetic positions—and the mediums of paint and photography—productively cohabit, unresolved, in her work.

Just down the road, at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, I encountered a strikingly different sensibility at work in Henrik Olesen’s retrospective. Olesen’s photographic compilations focusing on the criminalization of homosexual behavior and sodomy laws, his treatment of problematic family relationships (Mr Knife and Mrs Fork, (2009)), and his image and text narrative exploration of the physical and mental destruction of English mathematician Alan Turing (How Do I Make Myself a Body, (2009)), whose body was transformed by hormone treatments forcibly prescribed to suppress his sexual desires, exposed a rather bleak picture of gender, sexuality, and power past and present. While drifting on a small ferry from one shore of the Rhine to the other, and gearing up for a foray into Liste, the other major Basel art fair, I considered the social and political critique explicit in Olesen’s work alongside everything else I had seen, where such critique seemed on the whole rather absent. In that single, short moment devoted to quiet contemplation, it became far too clear to me how much the context of the fair—the sheer quantity and quality of everything on display, the constant sociability, the random connections and conjunctions between images, objects, and people—was over-determining and distorting my perception and experience. By the end of my five day stay, with my capacity for reaction stymied and my critical capacities dulled, I was honestly left wondering what strategy veteran fair-goers had adopted in order to cope with the sensory overload: harness winkers, anyone?