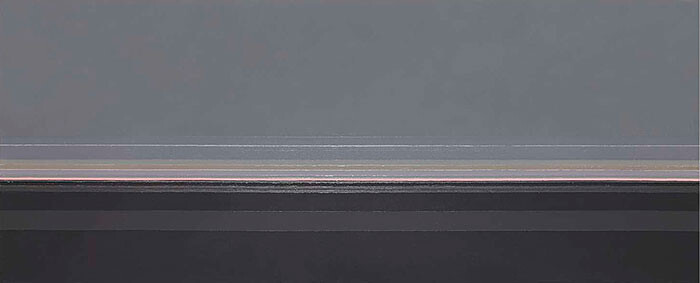

Liu Wei’s largest solo show to date deals with two main visual tropes—the horizon and the city. The first monumental sculpture we are confronted with is a megalopolis bristling with corporate towers perched high upon a bare rock, guarded further by a broad building in the shape of China’s national parliament, the Great Hall of the People. Made with compressed books to create a stripy strata that transverses the city and its rocky rampart, the relationship between China’s parliament and the massive commercial citadel behind it are thus successfully camouflaged. The stripes of the book pages are echoed in Meditation No.2 (2010) a painting in which a series of light and dark grey layers is intersected by a light pink line of the emerging (or receding) sunlight on the horizon. The perfect flatness of this painting is juxtaposed with the verticality of the urban sculpture in front of it.

Liu Wei’s new flat and empty horizon paintings—introduced for the first time in this show—follow a series called Purple Air that he employed to explore urban verticality over the last five years. The last painting of this series (of approximately 60 works) is displayed in a small antechamber leading to the main exhibition hall where a monumental group of architectural sculptures, Merely a Mistake (2010-2011), claim hegemony in the exhibition. The dominance of these structures relates not only to their size but also their architectural language. Resembling irrational cathedrals, their Gothic sensibility appeals directly to the senses. Lyonel Feininger’s Cathedral of Socialism (1919)—on the cover of the Bauhaus manifesto—springs to mind, an image that utilized a contradictory but logical marriage of religious messianism and communist utopianism.

Originally created for the 2010 Shanghai Biennale, these architectural sculptures were built of wooden debris from demolished buildings. Hence, the color and material of these structures harks to a recently bygone era. The re-appropriation of this material morphed into fantastical pseudo-religious objects points not towards the construction of a new utopianism, but instead to a dystopian mutation stemming from China’s current lack of spiritual or cultural direction.

But Liu Wei took the much simpler forms shown at the Biennale and continued to work-in more detail for this museum show. The almost cancer-like swelling of these sculptures now fill the large hall, mimicking, indeed, China’s urban sprawl. The social and material space where the small town meets the city is an important part of China’s strange cultural hybridism. Visual traditions of forms are stripped of all historical and cultural relevance, and their surface iconography is used without a sense of context. Liu Wei’s visual experiments relates to this side of China’s growth, which is as impressive as it is disturbing.

The presence of the horizon in the Meditation paintings throughout the exhibition is a symbolic antidote to this cancerous growth. The horizon is not only a place of new beginnings but also a destination that can never be reached. The horizon of the paintings finds its echo in the TV sculpture Power (2011). Made up of sixteen old cathode ray tube television sets stacked into towers, each screen displays a simple electrical signal of a single white line. They switch on and off at random, like being triggered by an unseen external stimulus, and each time a TV set shuts down, it emits a quick electrical cracking sound, reminding us of the analogue physicality of electrical power before our current digital age. These tangible but non-physical horizons present us with the 20th century utopian potential that television once represented, only to disappear with a loud thud. Horizons are, after all, a kind of fiction: they are non-places, or “no places,” that is, not unlike the original Greek meaning of Utopia, which has been replaced in China by a purely pragmatic belief in materialism. Liu Wei’s strange cultural growths in “Trilogy” capture this phenomenon in not too direct but effective metaphors, nevertheless.