Macho, violent, and angry: such is the America portrayed in Galleria Massimo De Carlo’s inquiring exhibition.

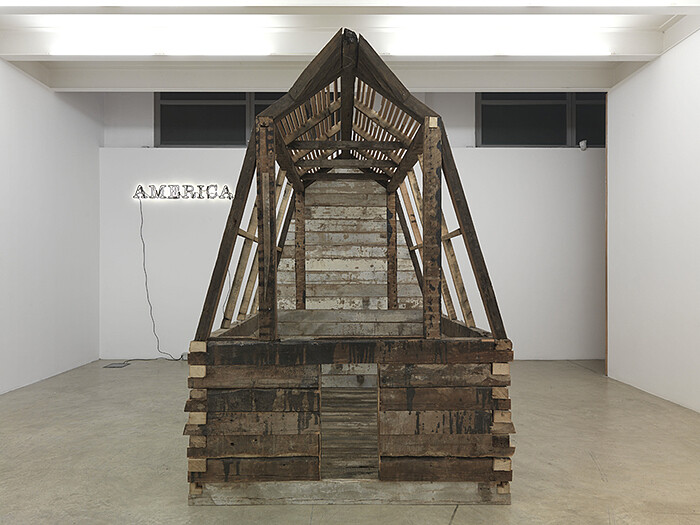

The show opens with the remnants of a ghost town, a derelict shed, and all that is missing is the tumbleweed. But here what’s being referenced is not the Wild West, but rather the myth of it created by Hollywood. Next to this Barn Again (2010) by Marianne Vitale, and complimenting the Western stage-set appeal, is a neon sign that reads “AMERICA”—more like a heralding gateway than caption to the room. This work by Glenn Ligon, The Period (2005), presents a contradiction: simultaneously it plays with the cliché of identity while assuming the legacy of modern American light works—from Flavin’s minimal glowing tubes, across the conceptual valley of ready-mades, only to arrive at Jason Rhoades’s colourful slang.

Around this arid, self-reflexive image of America, printed lyrics from almost forty decades of Afro-American musicians (from the poetic spoken word of Gil Scott-Heron to the arrogant rap of Nas) are crudely stapled to the wall like renegade manifestos of popular culture. In a way, this “mute soundtrack” provides a particular tone to the show dedicated to the imagery of North America and also opens up access to one of the lesser-known passions of gallerist Massimo De Carlo: music.

But notions of absolute dominance and power dwindle as the visitor enters the upper floor of the gallery. Facing us is a heavy black cross-symbolizing the decline of faith in industrial progress rather than the traditional celebratory notions of resurrection. Nate Lowman’s Black Tow Truck Broom (2010) resembles a crucifix of the industrial epoch and relates to Robert Longo’s equally disproportionate charcoal drawing, Untitled (Bodyhammer: Beretta) (2008). Like a Hasselblad ready to shoot a photo, the steady gaze reveals other threatening attributes, as it is in fact an oversized handgun—threatening to shoot, that is, in another form. Between a rock and a hard place, only madness and rebellion can offer a way out. In fact, Kaari Upson’s Untitled (2011), the remains of a bright aluminium sheet brutally set ablaze, appears as a call for action that brilliantly celebrates a whole filiation of creation through destruction.

This liberating eruption proceeds through Jack Goldstein’s Untitled (1983) in one of his famous attempts to capture a spectacular instant: a large painting of space delimited with barbed wire (a high-security prison?), a sky whose sharp, horizontal, red-and-white tear introduces a foreign, almost psychedelic element that invades any notion of realistic representation and, thus, proposes an exit via a radical cut with reality. Similarly, with Warped Hole (1992), Steven Parrino seems to take Goldstein’s depiction of an almost magic and intrusive phenomenon into a concrete gesture, pushing it toward a pictorial reflection. In doing so, Parrino breaks with the canon—that of Clement Greenberg, at least—by celebrating underground aesthetics made with industrial procedures and topped by a rock and roll attitude.

From one appropriation of a countercultural attitude to another, the image that closes the best of the worst possible Americas is, of course, Richard Prince’s re-photography of two Cowboys (1992): the paradigm of the dissemination (and surplus) of an American ideology so splendidly meaningless. An America we could never rejoice being in.