Text—as a never-finished, always-mutable, and labored process of thought—is the internal organizing logic of Amanda Ross-Ho’s recent production. The artist prepared the press release for her show, “A Stack of Black Pants,” as a sequential composite of paragraphs from the press releases accompanying her previous three exhibitions at Cherry and Martin. Rhyming quantity with chronology, it is made up of one paragraph from the artist’s first solo show (2006), two from her second (2007), and three from the third (2008). The resulting amalgam has been ruthlessly edited with still-visible redactions strategically striking through most of the recycled texts, leaving cherry-picked words and letters intact to create a new collective meaning. Occasionally, the continuous crossing-out is broken into staccato dashes by areas of bold red type in a slightly enlarged font that generates a tiered text floating above the field of slashed, rehashed sentences.

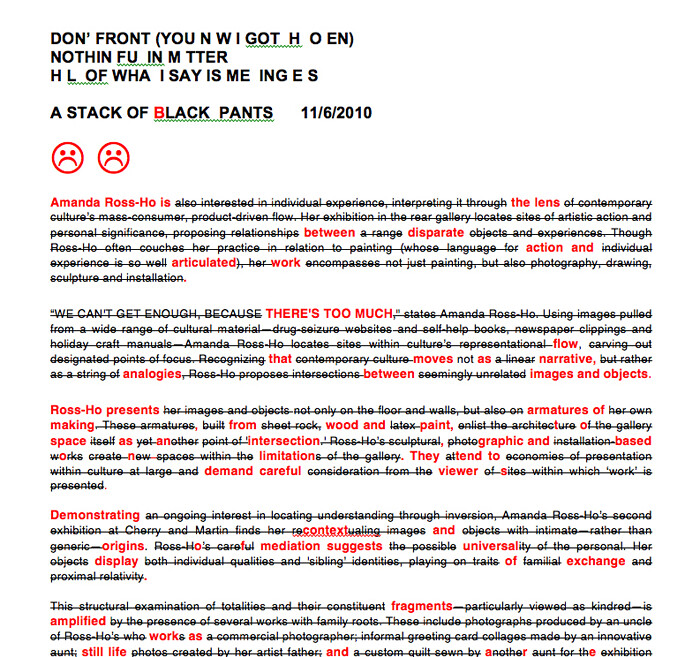

Writ in red (the instructor’s disciplinary ink), the new revised statement sets up the editing process and its cumulative measures of (re)assessment and modification as the foundational creative frame for this show. This is most explicit in a new series of “Correction” paintings—big (96 x 72 inches) white canvases bearing the red and black marks (checks, Xs, circles, subtracted points, looping Cs) of a teacher’s correcting hand minus the artist’s grade school homework on which the marks originally appeared. Spare and elegant, winking and accessibly clever, the “Correction” paintings are art-y, discrete, and smartly saleable. Yet, somehow, these very cohesive and convincing paintings that dominate the wall space are, oddly, the least memorable part of the show. Despite (or, more likely, because of) their appealing conceptual tidiness and available legibility, they seem perhaps too resolved.

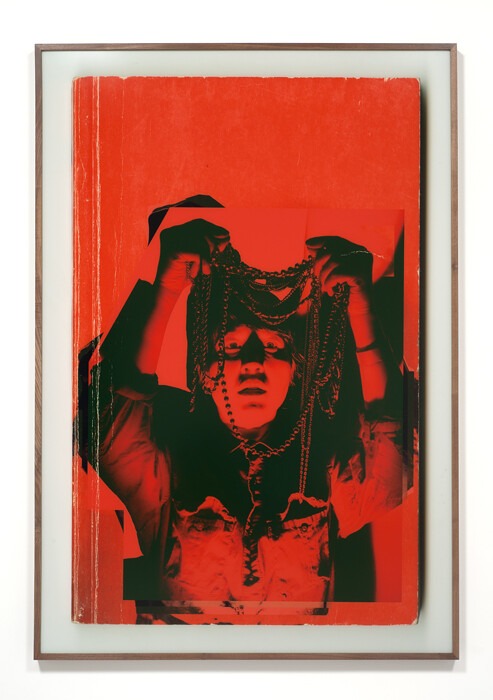

Instead, the idiosyncratic array of more discombobulating and anomalous pieces take mental precedence, linked by palette (predominantly black and white with shocks of red) and fluid, indirect lines of connectivity and shared mood. The small scribbled canvas Painting to Disguise One of Many Outlets (all works 2010) hung low on top of an outlet, while a photographic portrait of some electrified and stuffed-looking Bobcat creature hung in the other room. A framed piece of sheetrock (a bite-size version of previous relocations of her studio walls) was collaged with material fragments including “shoulder strap ribbons removed from H&M dress, aluminum thumbtack…single earring.” Cut acrylic and cardboard drafting right triangles leaned against the walls—blood red and connoting architecture, measurements, X-acto knives, the drawing board, Pythagoras and 6th grade geometry, rectitude, rules, and regulations. Gray wooden stairs—each with its own jug of Carlo Rossi Blush connected the floor to the wall like a hypotenuse leading nowhere. With its dangerous sword-sized pins, the backside of a hugely oversized, gold broach (with twin frowning tragedy masks) looked more like a glitzy coat of arms than a little old lady’s accessory. A teak pedestal displaying a stack of black pants—so gigantic they might have been stolen from the set of The Biggest Loser—reinstated the editing theme in corporeal terms of fatness, thinness, and weight lost.

Navigating connectivity between these elements primes us for the kind of careful viewing necessary to pick up on other, even more marginal and downplayed gestures which don’t quite make it onto the checklist. Mousy diagrams and notes scratched on the walls in smudged graphite are inconspicuous and could easily go unnoticed, walking the line between residual error and lavatory poetry. Two pairs of canvas Vans—one red, one white, and both dirty—line up along the sidelines. Single earrings and lonely pins are stuck with awkward charm into the drywall, little brass trinkets incongruously piercing the space like a body. Sometimes the most diminutive visual events dominate over the big ones, lodging themselves in memory with a force inversely proportional to their size, scale, object-ness, and loudness. Ross-Ho is right when she notes in her press release: “They tend to demand careful viewer[s].”