November 6–December 21, 2010

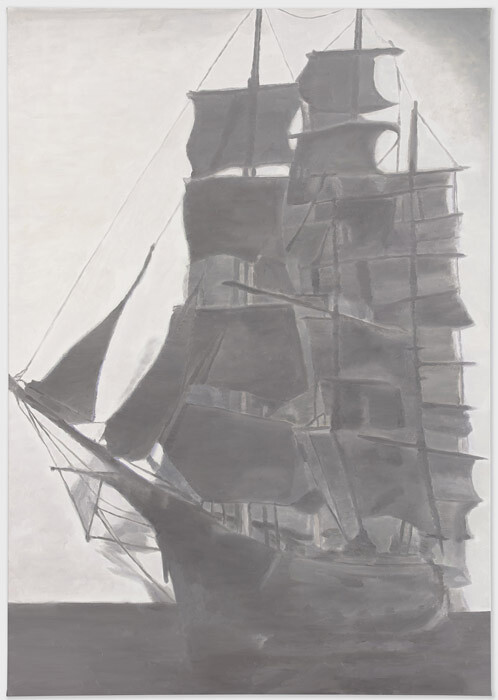

Luc Tuymans’s paintings set a somber mood at David Zwirner: a ship at sail with its stern to a cloudy horizon; a conspiratorial faceless portrait; a panel discussion dissolving as its participants are cast in blinding light. The 11 works in his latest show titled “Corporate” darkly depict corporations as the new feudal lords. This means a series of portraits, interiors, and landscapes in shades of gray line Zwirner’s walls, along with a girl on horseback and some knightly armor.

That Tuymans’s work takes “the banality of evil” as its subject matter—an often re-iterated point made again by curator Helen Molesworth in the artist’s retrospective catalogue at SFMOMA this spring—is only a half-truth here. His 17th century ship painting may evoke the same stillness of a Vija Celmins ocean painting, but it still fails to be quite so unsettling. There’s simply nothing remarkable about the composition, nor the artist’s loose brushwork, a point underscoring the larger problem within the show. The line between quiet and inert is much too thin.

Part of this has to do with the theme of the show, which is engaged only superficially. The subject of each painting ranges from the expected to the uninteresting. Two smoke stacks emitting scary poisonous clouds point to the industry behind the paperwork, a portrait of a manicured girl riding a horse represents the moneyed, the most commonly depicted class in any office. Corporate, a giant old ship reminiscent of those amongst The East India Company’s fleet is the first painting a viewer sees and is described as the first corporation. I’m no industry expert, but even Wikipedia sources ancient Rome as having legal business entities, so Tuyman’s chronology is more than a little challenged.

The depiction of the disengaged middle class is wholly absent, though the painting Fortis alludes to them. Titled after the banking, investment, and insurance firm, the piece consists only of a now bloody curved musical graphic once used in the company’s commercials issuing false promises to protect its clients. Talk about ham-fisted.

If the paintings resembled some of his more eerily deadpan works, I probably wouldn’t care what the subject was, but almost all them are dreadfully over-determined. Nowhere is the sensibility that produced the restrained bunny of 1994—The Rabbit—a tour de force of economic brushwork and form. Instead we’re offered Conference Room, a painting in which the backs of chairs melt into the walls as though the painter were aiming merely at half-assed abstraction.

Zwirner likely knew that Conference Room was the weakest painting in the show, as it almost disappears on a wall facing the back of the gallery. The painting directly opposite, Panel, eclipses this piece and every other in the show. CEOs don’t really talk to each other in public, so the work doesn’t have much to do with the theme of the show, but who cares? It’s at least a good painting. Bathed in the light from Zwirner’s skylights, Tuymans depicts an audience of dimly defined viewers watching four people on stage. The painting evokes the popes Francis Bacon so deftly portrayed, each similarly in a state of immateriality and anguish. But even if Tuymans wishes to draw comparisons between the abuse of power within the Church and those of corporations, his painting has more to say about the mythology of looking. In the case of Panel, the audience members are so blinded they no longer even know what they are watching. Sadly, I left with the feeling that Tuymans had expected as little from me as he had the spectators of Panel.