Der Kehlkopfverschlußlaut singt.

—Paul Celan

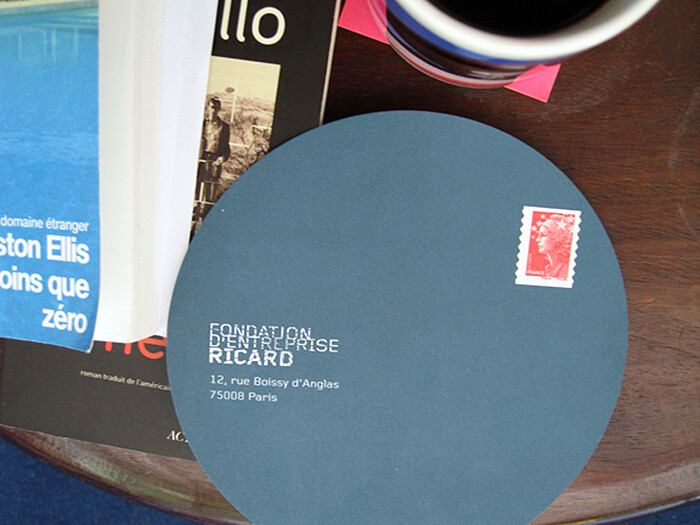

Considering the stigmas of alcohol and its abuses, advertising such products can be tricky. Cleverly, Ricard hit upon an idea: sponsor an eponymous prize at an art fair, throw a party for the winner, and then partner with the Pompidou to donate a work to the collection as the reward. With each step, the sponsor advertizes obliquely as the “class” of high art adds cachet to a cheap drink. An art fair, by definition, is a private affair, a purely commercial enterprise. However, what is curious today is that art fairs have also become expanded economic engines outside of the “art world” through their great elasticity for partnerships.

Ricard is not the only sponsor in on this game: planes, Air France; VIP chauffeured cars, Audi; lodging, Hotel Adagio; public art, the Tuileries Garden and the government. Even though the latter is a public-private partnership, there isn’t much to get upset about. This “show,” where galleries put out their crowd pleasers is just that—crowd pleasing. Capitalizing on this mass demographic, many major art institutions set their calendar for a knock-out show—just in case a few collectors and the like are in town—like, for example, the Adam McEwen curated exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, as part of their “carte-blanche” program, which incidentally takes its name from an open debt contract.

In the end, all of these activities enmesh so that the whole city is brought in—even the President comes to make a speech. As such, one has to ask, does the city, or at least its exhibition spaces, parks, clubs, etc., become the satellite or even the suburb of the fair? Inversely, how does the fair maintain its primacy? That is to say, instead of using the public sculptures as lures and justifications for subsidies, shouldn’t their marketing team have figured out a way to say that there is only the fair, that the Pompidou and the like are but a “day trip”?

The FIAC, like many other fairs today, presents a whole program of events, from screenings to performance and smaller exhibitions, some for a charge, others for free. This certainly adds to the festivities and promotes the idea that the fair is the center of it all. Yet, to achieve this gravitational goal, the overriding principle is diversity, and, with it, sprawl.

To be popular, a fair must provide something for all, that is, everything from the blue chips (Picasso) to street cred shows (i.e., Danny McDonald). Yet, like Ricard’s agenda, this diversity requires a “few intellectual cherries on top of the whole rotten cake,” to borrow a phrase from a colleague at another, just past fair, to make it look attractive.

At FIAC, the trend was toward a curated performance program, including a fantastic presentation of Guy de Cointet’s plays. Yet, in a counter-movement for those who argue that performance is some how anti-market, a William Pope L. performance was presented daily in a booth. All and all, the question remains if these “intellectual cherries” can ever be more than just that. Is there any space for criticality when it can be absorbed into the diverse portfolio-building trend? As a corollary to Bartleby, whose lack of performance can create pause in an industry, I was struck by a different use of the caesura whilst walking through the fair.

In his poem, “Frankfurt, September,” Paul Celan encounters the booth for the publisher of the deceased Kafka during a book fair. At this moment, Celan turns to ruminate on Kafka’s death from tuberculosis while looking upon the silent book morgue in which Kafka and his words are currently entombed. When responding to this, the poet uses a strange not unpronounceable word: Kehlkopfverschlußlaut. In translation, we learn that this word is the glottal stop, or the technical term for the sound represented by the hyphen in uh-oh!

This grunt, soft and agape, which stalls the breath, breaks the penultimate line of the poem. This break, like the pause in breath, picks up again on the last and ultimate line of the poem, a single word: “sings.” Here might be the only respite for the artists in this fair or others: the ability to commune with single works, which survive, under breath, as ghosts of the fairs’ totalizing economic zeitgeist.