Shameless nepotism or inspired programming? It’s hardly a surprise that Jeffrey Deitch’s first exhibition at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA would set critics atwitter, regardless of the subject, but watchdog fingers started wagging double-time with April’s news of a planned survey of the work of Dennis Hopper. Rushed by Deitch due to Hopper’s then-ailing condition (he passed away in May), the exhibition drew early concern, as Hopper was a collector of the work of exhibition curator Julian Schnabel; an actor in his film Basquiat; and the subject of one of his plate paintings. Deitch claimed to own the works of neither (“I have zero commercial involvement in this,” he told The Los Angeles Times), though as Steve Kaplan described on post.thing.net, it nonetheless “feels like an extension of the titillating, fame-obsessed, outré projects that often dominated his NY galleries.” If this is the case, then Deitch has simply adapted this one-man show for his new city, courting the celebrities, the crowds, and the culturati through Hopper’s unusual toeing of Hollywood and the art world. The only lingering question is whether Hopper’s art merits more than the industry chatter.

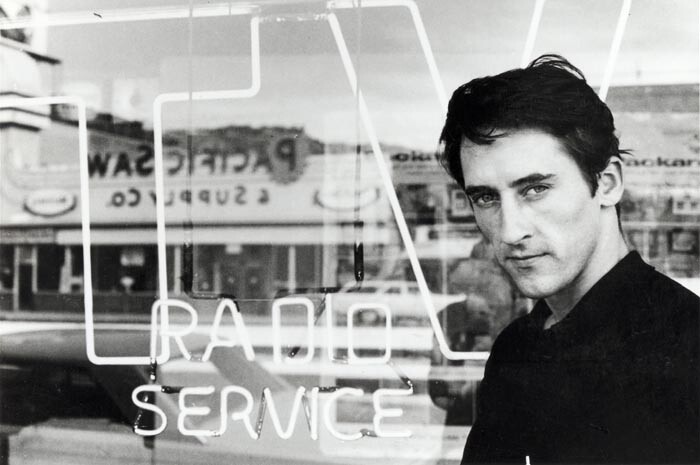

“Dennis Hopper Double Standard” comprises over two hundred works in various media that primarily date back to 1961, when a fire in Hopper’s Bel Air studio destroyed most of his earlier pieces. Best known among them are the black-and-white photographs from the 1960s of his notable friends, including Ed Ruscha, Wallace Berman, Larry Bell, and Bruce Conner. Shot in natural light and left uncropped, Hopper’s photographs have a cinéma vérité quality that lends to his effort, as he characterized in a 1999 Index Magazine interview, to document the emergent California art scene. In the strongest of these, the subjects turn a casual face that speaks to their intimacy with the photographer; or (in the unsurprising examples of Andy Warhol and Virginia Dwan) take on stiff, conspiratorial poses, as if to tacitly acknowledge Hopper’s role in their iconization.

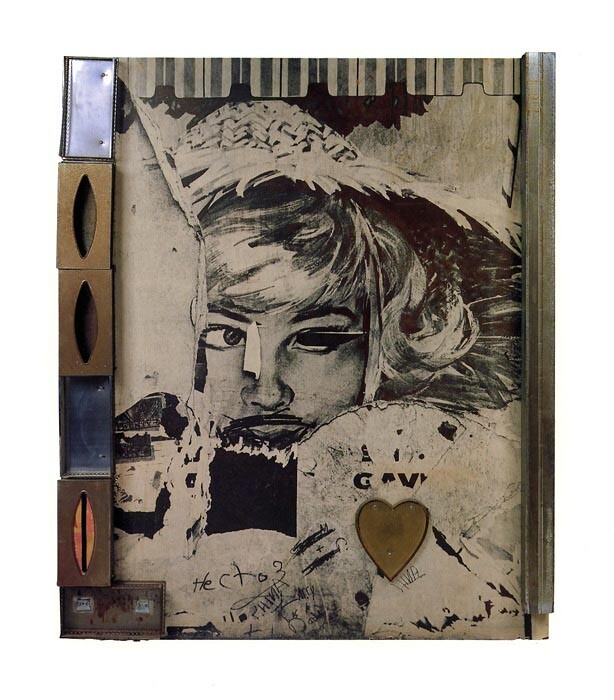

If Hopper’s photographs from the 1960s reveal the inquisitive eye of an aspiring film director, his work in sculpture, assemblage, and painting feels comparatively scattershot and unreflected—the emulative attempts of an avid collector who boasted about buying the first Campbell’s Soup Can painting in 1962 for $75, and of the fan who was so enthusiastic about Marcel Duchamp’s 1963 retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum that he solicited the French artist’s signature for a sign he stole from his hotel. Hopper’s imitations don’t have the naïveté of the uncultured or the cynicism of the anti-aesthete, however. They could rather be understood with reference to his studies with Lee Strasberg: the method actor as artist. So Hopper-as-Warhol exhibits a Pop placard entitled Coca-Cola Sign (Found Object), 1962; Hopper-as-Rauschenberg mixes found objects and photographic elements in combines like After the Fall, 1963; and Hopper-as-Eggleston angles his camera up to a red ceiling (Untitled [Venice Beach], 2005) or towards various other urban textures and details. As the decades passed, dominant styles changed, and Hopper’s references followed suit (Basquiat, McCarthy, Koons…). Notwithstanding the conviction evident throughout his broad body of work, he remained most at ease along the slender axis of the camera.