Workplace is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Canadian Centre for Architecture within the context of its year-long research project Catching Up With Life, featuring contributions by FICTILIS, Kim Gurney, Nahyun Hwang and David Eugin Moon, Alberte Lauridsen and Marianna Janowicz, Samiha Meem, Migrant’s Bureau, Kelly Pendergrast, Andreas Petrossiants, Arvand Pourabbasi and Golnar Abbasi, Nick Srnicek and Helen Hester, Denisse Vega de Santiago, and Dank Lloyd Wright.

Over the past five hundred years, two hundred years, one hundred years, thirty years, ten years, year, labor has changed. The way we work—the things we do, the ways and places we do them, who and what we do them with—has transformed. In parallel, so has our understanding of the world, of the city, of architecture, perhaps of life.

The ongoing dissolution of the spatial and conceptual boundaries delineating work from leisure, workplace from home, and worker from self has enabled productivity to position itself as a tenet of contemporary culture. Despite widespread automation and optimization, amidst the seemingly relentless demands of the gig economy, internet culture, remote work, and reproductive labor, many people continue to work as much as ever. Furthermore, each generation forms new notions around work. Gen Z, the first generation of true digital natives, are entering the workforce having grown up sharing themselves online. “The self,” that contemporary amalgam of image, relationships, tastes, and personality, has become commodified. For some, broadcasting oneself has become a viable profession in which the most private confines of the home and work have fully coalesced.

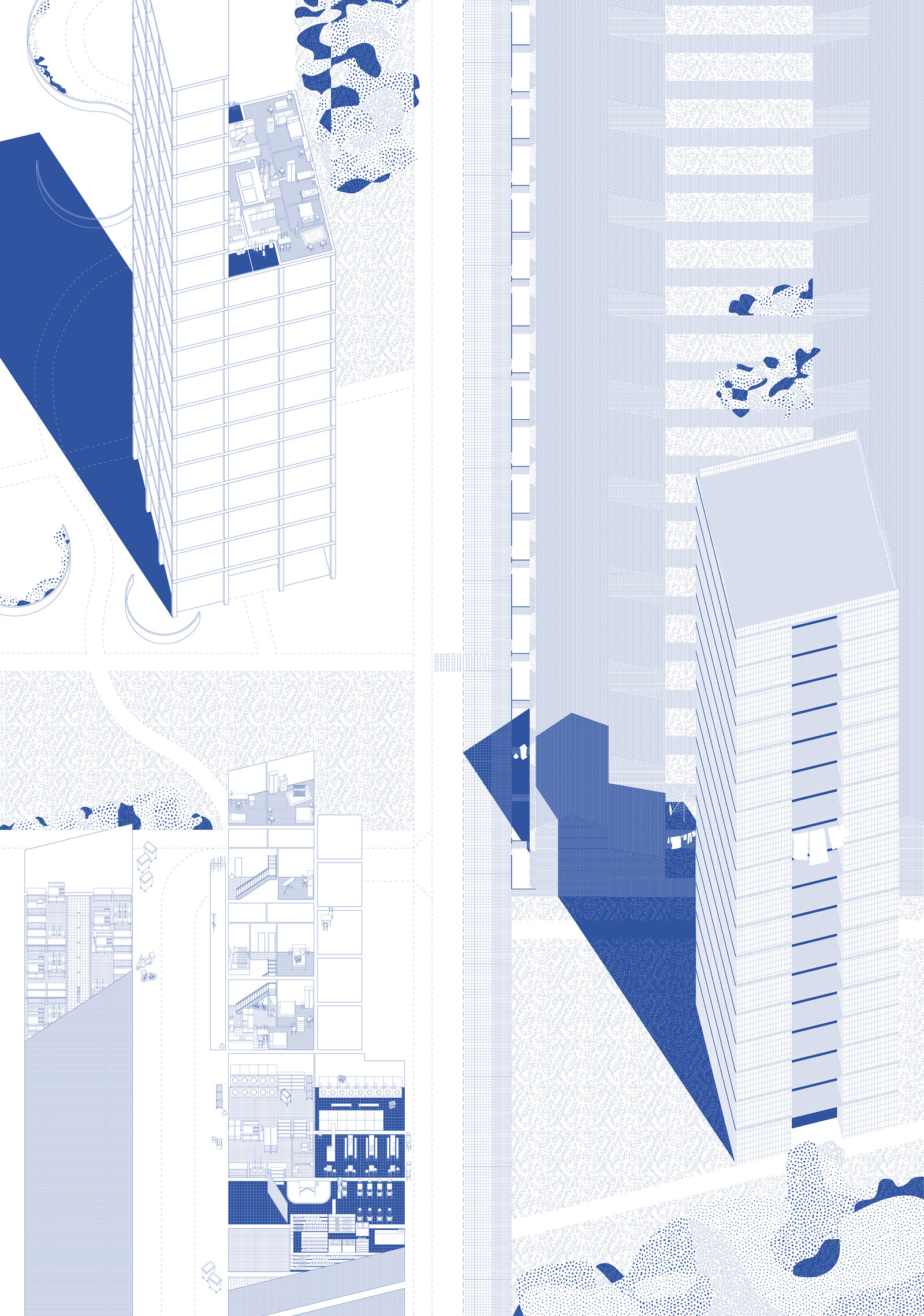

In many industries, this coalescence has recently undergone an intense development in the paring down of the workplace to you and your computer or your phone. What was, for a number of years, a theoretically possible rearticulation of work and place became for many an involuntary global experiment with a focus on the home during the Covid-19 pandemic. The scale of furloughs and layoffs during this time prompted many governments to offer social assistance in some form of basic income. But the reordering of values provoked by this shift towards the home is ambiguous. Some people whose jobs can be practically executed remotely have experienced a revaluation of work-life balance, such that they do not want to let go of their newfound abundance of domestic time, suffused with professional duties and video conferences as it may be. Certainly, this has the potential for progressive cultural, familial, and infrastructural outcomes, but no less could it produce a precarious model of employment that aggravates prevalent inequity and exploits new degrees of flexibility to gain greater capital.

Because even though labor, the city, and our lives within it may look or feel different does not mean it all doesn’t work the same as it used to; that it doesn’t still operate according to persistent and primitive logics of extraction, accumulation, and exploitation. Labor is a relation, not just between people but also between spaces, things, and ideas. And architecture has always been the stage upon which labor—and its struggles—takes place. Let us not be fooled by the illusion of novelty, disruption, or change. Technological development only tends to deepen, complexify, and reinforce iniquitous power relations and their spatial manifestations relations rather than bring about entirely new paradigms. If the revolution is already here, it’s not very evenly distributed. What, then, are the conditions of labor within which attempts for equality, dignity, and rights are being made today? Where is the front line, and who is fighting the good fight?

Workplace is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Canadian Centre for Architecture within the context of its year-long research project Catching Up With Life.