And if the wreckage of this inheritance will not be complete; if notwithstanding the crimes committed during this “civilized” war, we may still be sure that the teachings and traditions of human solidarity will, after all, emerge intact from the present ordeal, it is because, by the side of the extermination organized from above, we see thousands of those manifestations of spontaneous mutual aid.

—Peter Kropotkin1

1. The Dilemmas of Mutual Aid

At the dawn of the first World War, Peter Kropotkin’s preface to the 1914 edition of Mutual Aid transmits a specific kind of optimism rooted in his observation that collective care is an innate characteristic of biological and social life. Rather than being “idealistic” and starry-eyed, as dishonest detractors would claim in the years to come, his theory is utopian: a utopianism nested in a very specific realism developed by observing plentiful examples of animals engaging in mutual aid in the woods of Siberia, as well as in human, urban domains across the world. In a new edition of Kropotkin’s book released by PM Press in 2021, the late and sorely missed David Graeber and Andrej Grubačić contextualize the original text historically and in the present.2 They first describe numerous reactionary responses to Kropotkin’s book from the early 1900s to the present: the far right who relegate him to the role of “crackpot”;3 liberals who desperately and acrobatically contort to reconcile his theories with competition (both evolutionary and social); and lastly, sectarian Marxists-Leninists who, according to Graeber and Grubačić, “pretended [Kropotkin’s] intervention had never occurred.”4

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic many constellations of mutual aid cropped up all over the world in response to the appalling results of decades of global austerity that made themselves apparent beyond the typical sites of neoliberal neglect. In New York City, where I live, one need only look at the list of groups collected on Mutual Aid NYC’s website to see the extent of the networks.5 Most began as food distribution or shifted their prior infrastructures to give out material necessities. During the George Floyd Rebellions, many transitioned to handing out personal protective equipment and other supplies at protests and demos, formed jail support networks, and raised money by selling art to bail out protestors and pay legal fees for those threatened with incarceration. Some formed (guerrilla) gardens or came together to help rent strikers sustain themselves. All the above actions are part of that very same “human solidarity” Kropotkin speaks of in the epigraph, that which may in fact help people “emerge intact from the present ordeal.”

At first, many of these nascent formations kept to the historical, anarchist conception of “mutual aid” as a form of collective survival organized autonomously and specifically in contrast to charity. Charity operates from above and valorizes accumulated wealth, while mutual aid works horizontally and transforms the exchange values of commodities into use values. This can be accomplished by collecting donations or looting means of subsistence to distribute them freely, or by creating infrastructures distinct from existing avenues of social reproduction that come with hefty strings attached. Indeed, as the Art Workers’ Inquiry group of Red Bloom Communist Collective defines it:

Unlike charity, mutual aid does not function according to a logic of morality… Mutual aid is a relation that builds working-class power, solidarity, and capacity, enabling the working class to experiment with self-determined structures of care that begin to offer alternative forms to capitalism.6

However, during the pandemic in New York and elsewhere, problematics within some mutual aid groups emerged. Some groups began to devolve into charity as they disconnected from a political project. Others got stuck in the dilemmas of scale—for example, deciding whether the potential to serve more people necessitated making concessions to political actors or aligning with nefarious organizations.7 To add to this fraught landscape, elected officials worked tirelessly to absorb mutual aid into the logics of the state, playing a tightrope game saluting the plentiful examples of autonomous work while giving off the air that governments were doing the most they could. Nonetheless, city administrations across the US could not fully account for their complicity in countless deaths. In the twenty years leading up to the pandemic, for example, New York City lost twenty thousand hospital beds to the continued privatization of medicine.8

That these issues were confronted does not mean that one should write off mutual aid as temporary responses to capitalist crisis prone to the pitfalls of “unorganized” formations, as some democratic socialists or communists might do. Rather, the sheer breadth of mutual aid can help see how creating infrastructures of survival apart from the state is integral to lasting beyond any one point in the larger crisis of capitalism. Furthermore, understanding the longevity of mutual aid outside of the temporalities of crisis demonstrates how to avoid co-optation by the state’s welfare apparatuses. Lastly, as this text will argue, the participation of artists in various forms of mutual aid, from food distribution to jail support and eviction defense, signals that looking to radical communities that cultural workers help create and participate in can be a template for scaling sideways (across class, occupation, and other forms of capitalist subjectivation) rather than aspiring to growth in a capitalist framework.

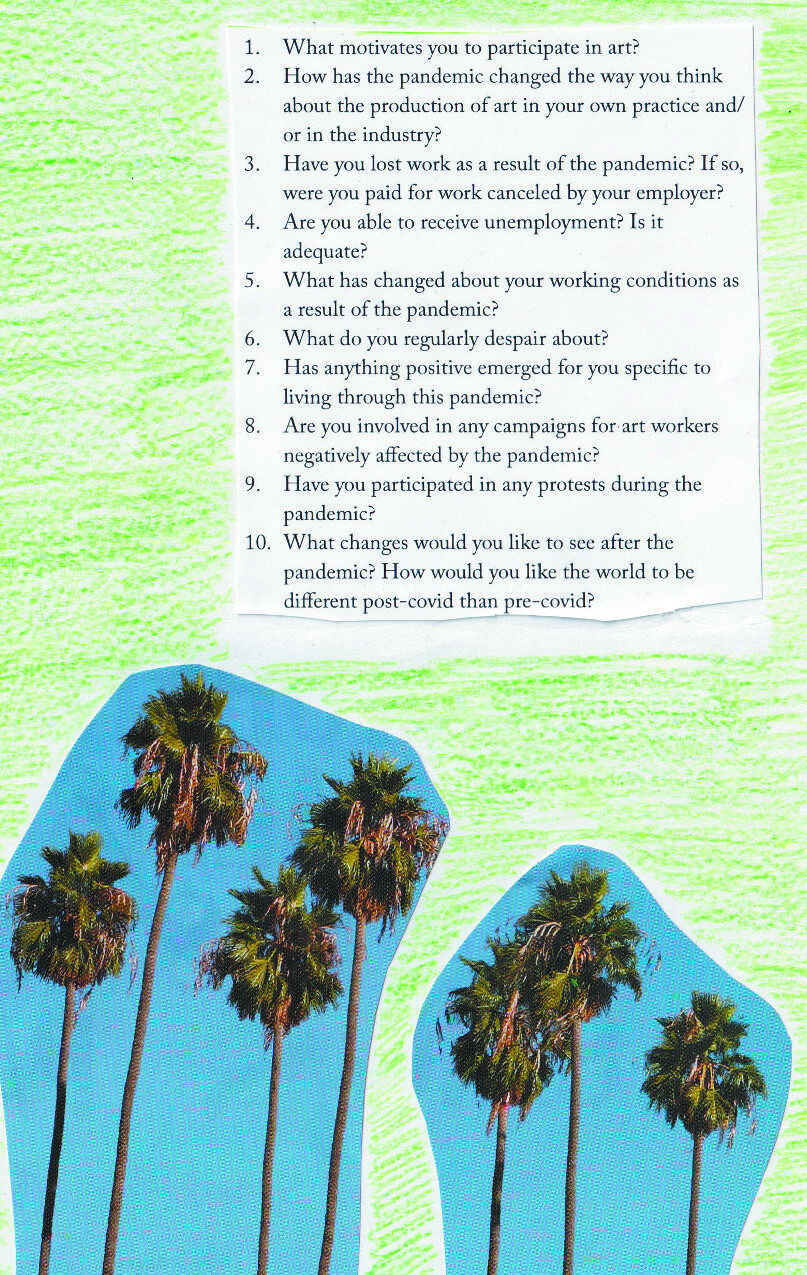

Questions from the Art Workers’ Inquiry in Art Work During a Pandemic (2021).

2. Breaking the Cycle of Crisis and Recuperation

The standard story of mutual aid is that it is born in response to crisis. This is, at least, how crisis management and liberal, capitalist ideology puts it. All the same, it is partly, demonstrably true. After Hurricane Sandy in New York, for instance, autonomous and horizontalist networks from Occupy Wall Street were able to quickly shift their focus to aid under the banner of Occupy Sandy.9 But mutual aid should not only be understood as a reactive phenomenon. Kropotkin certainly didn’t see it that way; his theory came in response to conversative sociologists and evolutionary psychologists who erroneously appropriated Darwin’s studies to suit capitalist historiography and vice versa. Kropotkin saw collective forms of survival as part of “an instinct that has been slowly developed among animals and men in the course of an extremely long evolution, and which has taught animals and men alike the force they can borrow from the practice of mutual aid and support, and the joys they can find in social life… It is the conscience—be it only at the stage of an instinct—of human solidarity.”10 But beyond universalist and biological notions of mutual aid’s intrinsic qualities—evincible as they may be and as vexing as they are to contemporary scientists desperately seeking a reconciliation between altruism and the perceived “naturalism” of the market—a quick glance at history shows that mutual aid structures also anticipate crises and mitigate them when they arrive.

By its very constitution, the capitalist nation state must be quick to absorb that collective preparation, take responsibility for it, lest it become clear that the state cannot provide, that it is in fact unnecessary and harmful. Described succinctly by Graeber and Grubačić:

The late nineteenth century and early twentieth saw the foundations of the welfare state, whose key institutions were, indeed, largely created by mutual aid groups, entirely independently of the state, then gradually coopted by states and political parties. Most right and left intellectuals were perfectly aligned on this one: Bismarck fully admitted he created German social welfare institutions as a “bribe” to the working class so they would not become socialists.11

City governments across the United States have already begun instituting publicly funded “mutual aid” jobs. But, how can this be seen in any another way than the first step to absorbing collective power to render it powerless? To anticipate this process, some specificity is required. Asad Haider, for example, makes a helpful distinction between “neutralization” and “co-optation,” or recuperation. He writes:

What I mean by neutralization is a force which renders opposition ineffective. It is distinct from the potentially moralistic idea of co-optation, which presumes some authentic belonging of the object. Opposition is neutralized not through appropriation, but through the formulation of an effective reactant and the transformation of each element into a new compound… Neutralization comes from the top. It contains and redirects opposition into the harmonious diversity of the system.12

Taking this framework, it becomes clear that for forms of collective care to become neutralized as popularly accepted functions of the state, they must first be co-opted. Once accepted as such, they can then be subject to austerity. And as with most forms of statist neutralization, it is done through the carceral apparatus. As Peer Illner puts it: “States have been quite happy to let communities perform this type of [mutual aid] work for free, as long as they don’t organize politically in a way that threatens local governments.”13 In the US, perhaps the most cited historical example of this was the recuperation of the Black Panther Party’s (BPP) Free Breakfast for School Children Program, which FBI director J. Edgar Hoover described as one of the biggest threats to American power.14 After extrajudicially murdering, framing, and incarcerating members of the BPP, the federal government soon implemented its own breakfast for kids program built on the framework of the Panthers.15 However, following the pattern sketched above, the US’s program is today “failing to live up to its potential.” According to a study by the Food Research and Action Center, “the program is falling short by at least ten million students, if not more.”16

In his book Disasters and Social Reproduction: Crisis Response Between the State and Community, Illner argues that mutual aid risks allowing the state to shirk its “duties” by relying on mutual aid parallel to this process of absorption. This argument, however, is itself dangerous, and clumsily puts (at least part of) austerity’s blame on those creating networks to survive, somewhat like how liberals and “professional activists” may blame demonstrators for police violence if those in the street do not conform to sanctioned forms of protest. The goal of mutual aid should be to wrestle tasks from the state while defending against their capture.

Another common misconception with mutual aid can be found in Illner’s writing on the 2021 blizzard in Texas. Referencing the International Wages for Housework Campaign (WfH), he claims that mutual aid organizers on the ground in Texas could ask to be remunerated (by the state, ostensibly) for their work. However, this argument forgets that Silvia Federici’s seminal text for the movement was titled “Wages Against Housework,” not as it is so often reproduced “Wages for Housework.” That distinction is crucial. Though there were multiple branches with differing opinions, Federici and her comrades in WfH were less interested in this ultimately statist socialist demand to get paid for housework, but rather in abolishing the wage and the necessity to be paid in order to survive in the first place. Maintenance work isn’t going anywhere: it takes “all the fucking time,” as artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles put it perfectly in 1969. But wages should, and could. The work in Texas as well as other mutual aid networks appearing today make those possibilities clear.

One of the most promising proposals to break out from the cycle of aid, recuperation, austerity, and incarceration, was proposed during the pandemic by the Queens cultural hub Woodbine as an alternative to “disaster communism.” Bridging the work of caring for one another with the work of building our own infrastructures, they propose “disaster confederalism” that would provide “the conditions for a kind of infinite strike in which communized resources and infrastructures have a crucial role to play, not only in immediate material survival but in building bases of autonomy for a citywide network of dual power.”17 Here, rather than embracing the subsumption of mutualist work to the logics of the wage, the goal is in producing self-sustaining and cooperative forms of engagement with one another outside of those logics.

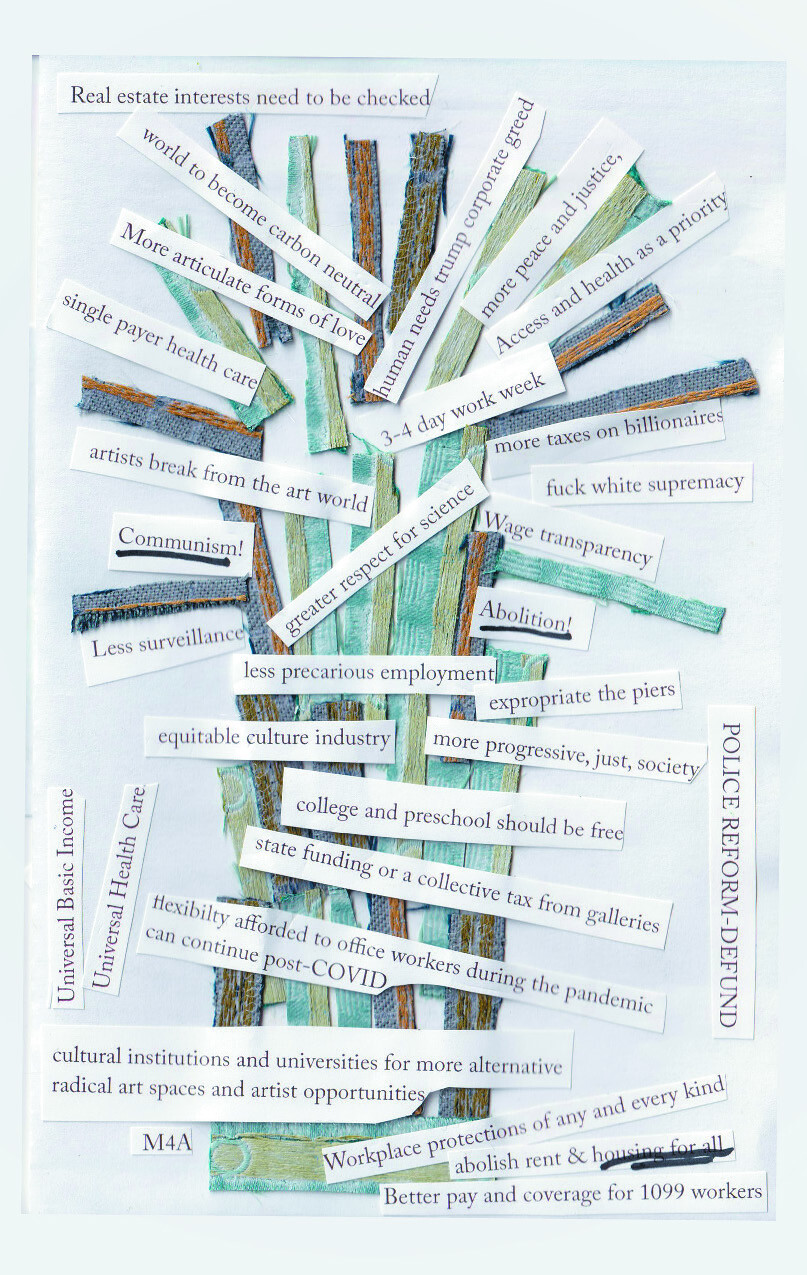

Responses to the question “What changes would you like to see after the pandemic?” in Art Work During a Pandemic (2021).

3. Retooling, Not Reskilling

In contrast to classical aesthetic theory, which had it that art is other to labor, understanding art and cultural production as work is the very precondition for artists to participate in liberation struggles large and small. As I was contemplating this text, Common Notions published a zine put together by Red Bloom Communist Collective: an art workers’ inquiry in the spirit of Marx’s unrealized 1880 inquiry for La Revue socialiste, and later others like the workerist Quaderni Rossi in Italy and the Johnson-Forest Tendency in the US. It demonstrated how artists and art workers can relate to mutual aid work and in building popular power in their communities. Artists and art workers have skills, networks, and supplies that when taken together with others help create infrastructure(s) that can be used or re-tooled in the interests of abolition, struggle, and collective care.

Responses to an inquiry about life “after” the pandemic included: “no cops,” “communism!,” “free MTA,” “college and preschool should be free,” “Abolition!,” “abolish rent and housing for all!” Among them are also many that hope for an expansion of mutual aid: “I [would] like to see the rich run scared and the rest of us really truly do the work we need to do to keep each other safe,” and “the world to have a better understanding of the myriad and intricate ways humanity is connected and co-dependent across the globe.”

Following the work of Marina Vishmidt, there is revolutionary potential in what she calls an “infrastructural critique”: a form of cultural and political antagonism that sees the potential for creating extra-parliamentary, autonomous infrastructures of care, mutual aid, and so on both within and outside of existing supply chains.18 What, then, if we were to not think of artists as defining a “class” of workers, one exceptional to the capitalist mode of production, but rather as potential, and integral, parts of communities already interwoven with others like neighborhoods, autonomous unions, and party scenes? Red Bloom’s definition of community illustrates this:

A community is a group of people with some shared characteristic: they may live in the same place, work at the same job, share an experience of being a mother, pet owner, etc… But what does it mean to be in community? For community to be a praxis? A community is grounded in mutual dependence and recognition… Mutual aid is a means of building community, and both mutual aid and community work against the alienation that only serves to weaken our ability to self-organize.19

This understanding of community is another way to connect what is done in larger networks (municipal sanitation, food production, medical care even) with self-organization and self-management common to much artistic and cultural work. It shifts the veneration of skills sellable on the free market into tools that are available to communize. For instance, during the early parts of the pandemic, a new organization called Art Bailout NYC collected donations for a bail fund, with artists retooling their networks (of buyers and producers) and sellable objects into a decidedly different abolitionist pursuit. Artist Luba Drozd used machines and tools available to her (through institutional and personal spaces) to 3D print shields for front linters and distribute them to hospitals with a team of volunteers. Woodbine shifted almost entirely to distributing food to thousands every week, using their space which was typically reserved for cultural events and organizing meetings. Take Back the Bronx and NYC Shut it Down, two community groups fighting gentrification and police violence, expanded their Feed the People (FTP) food and clothing distribution to respond to new needs like hygienic and sanitary products.

What if all the new mutual aid formations developed during the pandemic were not built as a reaction to temporary crises, but for longevity? Similarly, what if the spaces managed and organized by artists and the skills and networks cultivated by new, numerous mutual aid networks were put to the ends of creating permanent structures of collective social reproduction, consumption, and aid? Quoting “How to Start a Fire,” a text that spread during the George Floyd rebellions:

Pirate radio. Build stoves. Learn to cook. Learn languages. Get arms. Open street carts and businesses. Occupy building. Set up cafes. Diners. Restaurants. … Permaculture. Mend wounds. Lathes. Giant pots. Orchards. Build friendships. … Get cars. Steal money. Move close to each other. Start uncontrollable riots.20

The secret to mutual aid being sustainable (rather than scalable) is realizing that everything in that list is mutual aid if it’s done with a rejection of philanthropy, hierarchy, and not-for-profit co-option. Mutual aid is a political practice that sees collective care as permanent, and artists, many of whom live in and comprise precarious communities, know that as well as anyone else.

Preface to the 1914 edition of Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (London: Heinemann, 1914).

David Graeber and Andrej Grubačić, introduction to Mutual Aid: An Illuminated Factor of Evolution (PM Press, 2021), ➝.

This term, however, comes from Stephen Jay Gould’s text “Kropotkin was no Crackpot,” ➝.

Graeber and Grubacic.

See ➝.

Art Workers’ Inquiry, Art Work During a Pandemic (Red Bloom Communist Collective and Common Notions, 2021), 52. (page numbers refer to the PDF pages of the zine and may not correlate to the printed copy.)

The thought that one needs to constantly scale up is a trap, set up by the existing social order to prescribe collective action into codified and extractive systems of social reproduction and growth. Beautifully put by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten: “scaling up is really scaling down, losing connection rather than gaining it, losing abilities rather than consolidating them, settling for form rather than formation.” Stefano Harney, Fred Moten, Sandra Ruiz, and Hypatia Vourloumis, “Resonances: A Conversation on Formless Formation,” e-flux journal, no. 121 (October 2021), ➝.

Elected officials blamed “irresponsible” people for crowding the hospitals. While Covid-19 was certainly something that could not have been avoided, systems (of medicine, housing, food distribution) across the West has been set up in recent decades to guarantee a poor response. See: ➝.

See Rouen dans la Rue, “Solidarity and Collective Autonomy: An Interview with Woodbine,” Mute, April 20, 2020, ➝.

Peter Kropotkin, introduction to Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (McClure Phillips & co, 1902), xiii, ➝.

Graeber and Grubacic.

Asad Haider, “Emancipation and Exhaustion,” South Asian Avant-Garde: A Dissident Literary Anthology, March 10, 2021, ➝. This essay, and citation were brought to my attention when reading Keith Ocheing Okoth’s stellar “Decolonisation and its Discontents: Rethinking the Cycle of National Liberation,” Salvage, no. 10 (Spring/Summer 2021).

Illner, 18.

A less-referenced example is the work of the Young Lords in instituting syringe exchange programs. See M. E. O’Brien, “Junkie Communism,” July 15, 2019, ➝.

Another interesting example is studied by Sean Michael Parson who makes the case that city governments in San Francisco were much more violent with those handing out food with the anarchist group Food Not Bombs than others squatting homes in the 1980s and 90s. He writes: “While squatting would seem to be a graver offense than distributing free food, Homes Not Jails was treated far more leniently by city officials during the Jordan administrations. I trace the difference in v treatment of the two groups to the fact that Food Not Bombs engages in anarchist direct action in public space, while Homes Not Jails does so in private residences. The public nature of Food Not Bombs made them a visible threat to order to both Agnos and Jordan and one they had to confront and stop.” Sean Michael Parson, “An Ungovernable Force? Food Not Bombs, Homeless Activism and Politics in San Francisco, 1988–1995, (PhD diss., Graduate School at the University of Oregon, 2010).

Roberto A Ferdman, “How Our Schools Fail Poor Kids Before They Even Arrive for Class,” Washington Post, February 18. 2015, ➝.

Woodbine, “Organizing for Survival in New York City,” Commune, April 24, 2020.

See Marina Vishmidt in conversation with Andreas Petrossiants, “Spaces of Speculation: Movement Politics in the Infrastructure,” Historical Materialism, online, ➝.

Art Work During a Pandemic, 47.

Available here: ➝.

Workplace is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Canadian Centre for Architecture within the context of its year-long research project Catching Up With Life.