Picking a present for an old friend can be difficult. The perfect gift has the right size (not too small, but not too extravagant either), is highly personal, and should leave a lasting impression. If you really want to impress, it should also be something that took a big effort on your part.

Keeping these rules in mind is difficult enough when your old friend is, in fact, a human. Imagine the hassle you’d go through when picking a present for an entire continent! Yet this was exactly what Chinese leaders did. To show the depth of their countries friendship for Africa, they came up with what they considered a truly special gift: a new headquarters for the African Union.

It took them no more than three years to finish construction of the striking, 200 million US dollar new assembly house in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa. When it opened its doors on 26 December 2011, it was Addis’ tallest building, making it a landmark icon that is visible from virtually every angle of the city. It was a Chinese effort in every detail: it was commissioned by the Chinese ministry of Commerce, designed by the Tongji Urban Planning & Design Institute in Shanghai, and constructed by the China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) with some 1,100 on-site workers, roughly half of whom were Chinese. Most of the construction materials came from back home as well.

The African Union building is exemplary of China’s “stadium diplomacy,” handing out buildings and sport stadiums to strengthen ties with African governments. These landmarks do not only symbolize the strong and fast rise of urban Africa, but also make a clear statement: China is more than willing to play a role in shaping the African future.

The signs are visible in important infrastructure developments all over Africa, such as the Thika Super Highway in Kenya or the new light rail system in Lagos, Nigeria. Just like Addis Ababa, many fast-growing cities in Africa got a new skyline, “Made in China.” Or, as a Rwandese architect told us: “Every building of more than five stories was designed by a Chinese architecture firm, financed by a Chinese bank, built by a Chinese contractor, with Chinese concrete, Chinese outlets, window frames and fire extinguishers, decorated with Chinese carpets and curtains. And everything was put together by Chinese construction workers.”

Until not so long ago, mass housing developments in Africa were almost synonymous with slums. But the impressive economic growth of the past decade has created a sizable middle class that no longer accepts substandard living conditions for their families. The first modern housing developments start to appear. And of course, China’s contractors are trying to get a piece of the pie. The “Great Wall Apartments” on Beijing Road in Nairobi are exemplary of the walled compounds you can find in almost every Chinese city. China’s most impressive urban achievement in Africa to date is Kilamba Kiaxi, a new suburb just outside of the Angolan capital Luanda for more than 500,000 people; designed, built and financed by a consortium of Chinese state-owned companies.

Not everyone is cheering China’s efforts. When she was still US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton warned Africa of “a new form of colonialism.” Without wanting to get into an unproductive moral discussion, it is interesting to know whether Africa’s cities are indeed developing “the Chinese way.” In other words, does China successfully export (parts of) its highly successful growth model that it developed in the past thirty years?

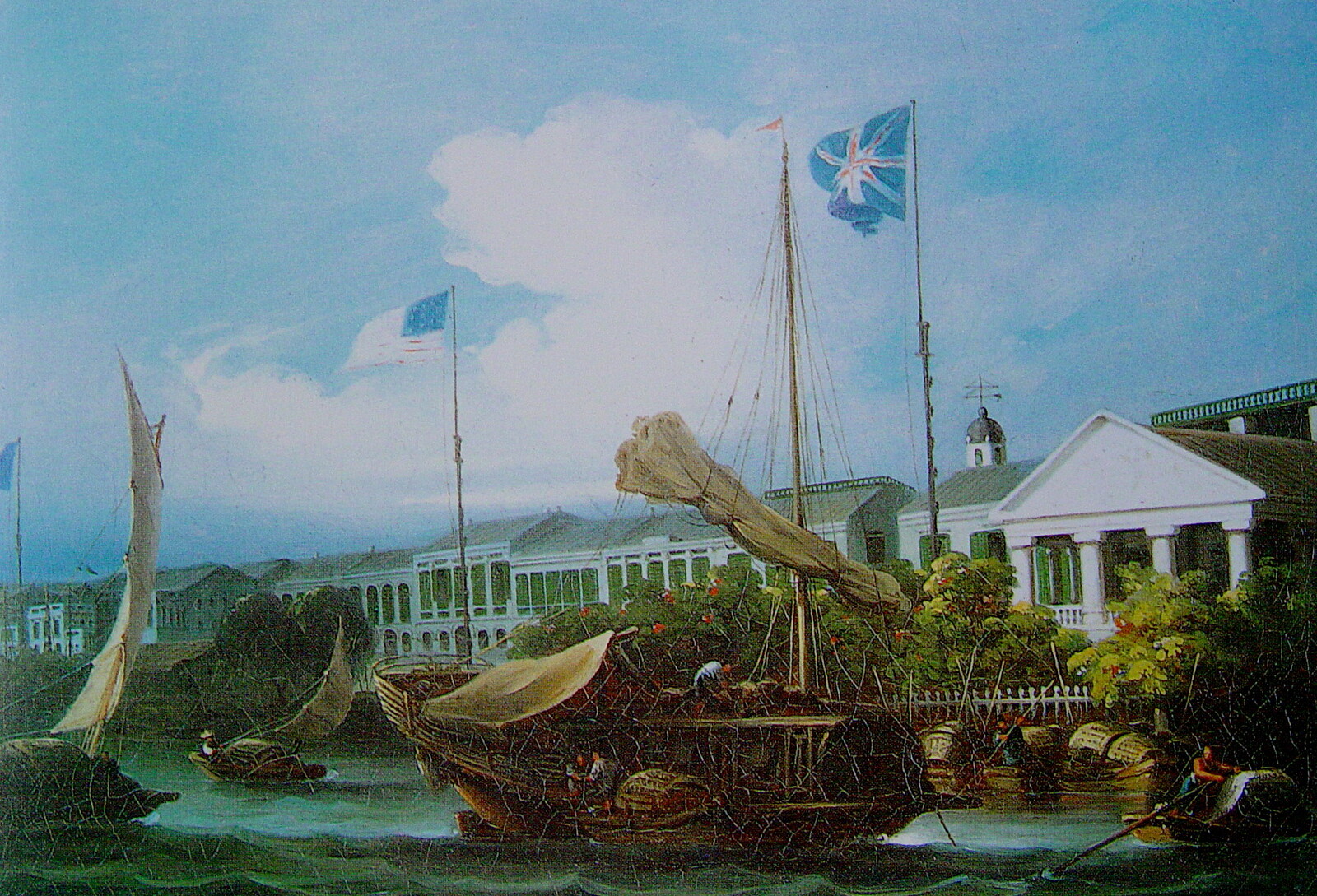

To answer this question, we can look at one of China’s most comprehensive methods for urban development: the Special Economic Zone (SEZ), a specific geographical area closed off from the rest of the country that has more liberal economic laws and preferential policies that aim to attract investors and create jobs. Although SEZs have had de facto existence since the eighteenth century—Gibraltar in 1704, for example, and Singapore in 1819—it was China that led the way in applying the model as a strategy for urban development. The first four Chinese zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen, created under the rule of Deng Xiaoping, were instrumental in attracting foreign investment. Each are conveniently located on the coast, close to Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, which all boast a wealthy Chinese diaspora that could be attracted by preferential tax rates and the possibility of cheap labor in the Mainland.

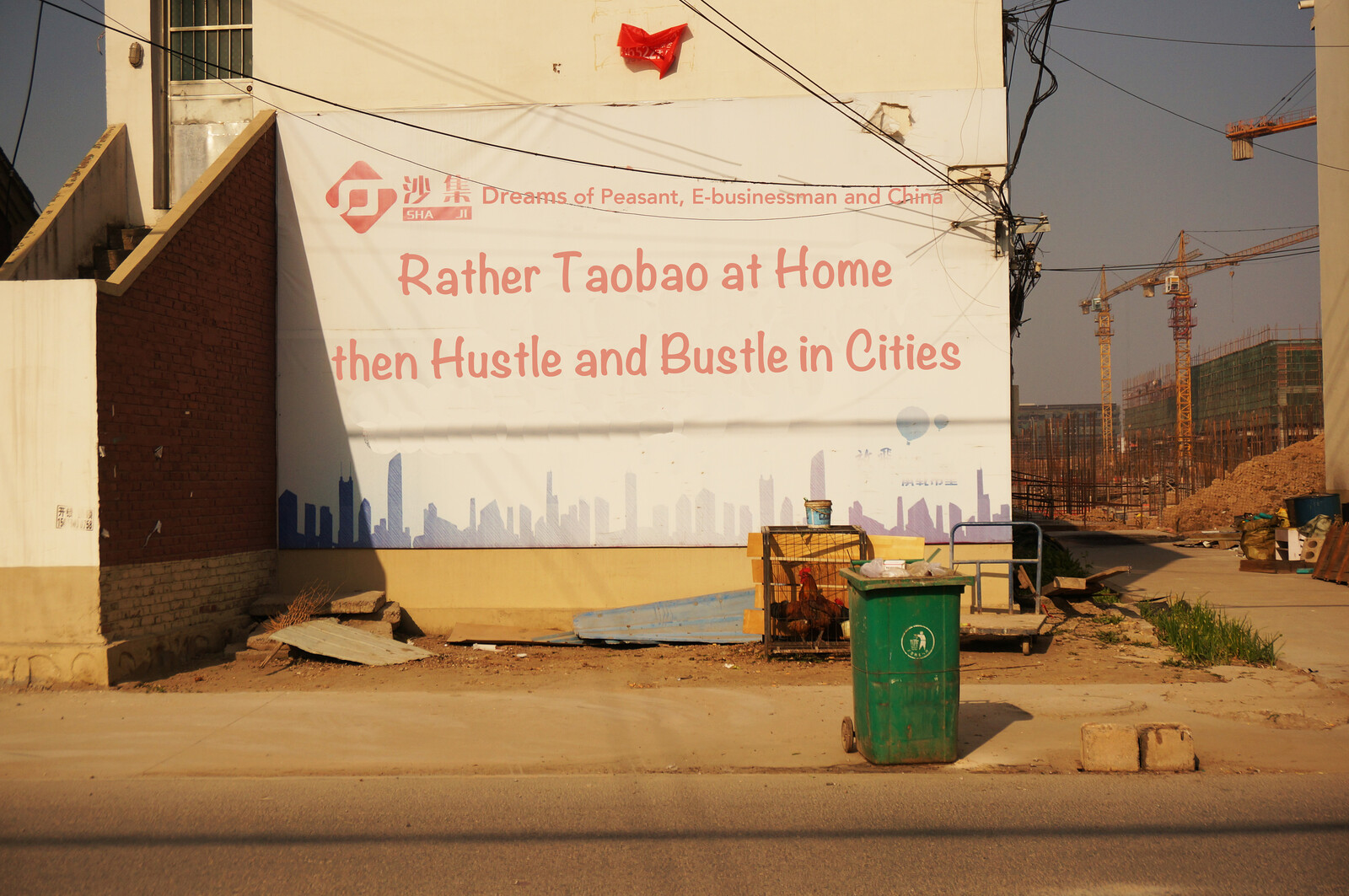

Like no other city, Shenzhen represents the flagship for China’s rise from a poor, agricultural country to its current “factory for the world” status. In three decades since the start of the Shenzhen SEZ in 1979, the fishing town has transformed into a bustling megacity of fifteen million inhabitants at the center of the Pearl River Delta. The success of Shenzhen has prompted policy makers to develop over a hundred more economic zones of different types all over China. And now, they feel, it’s time for the SEZ to travel to Africa.

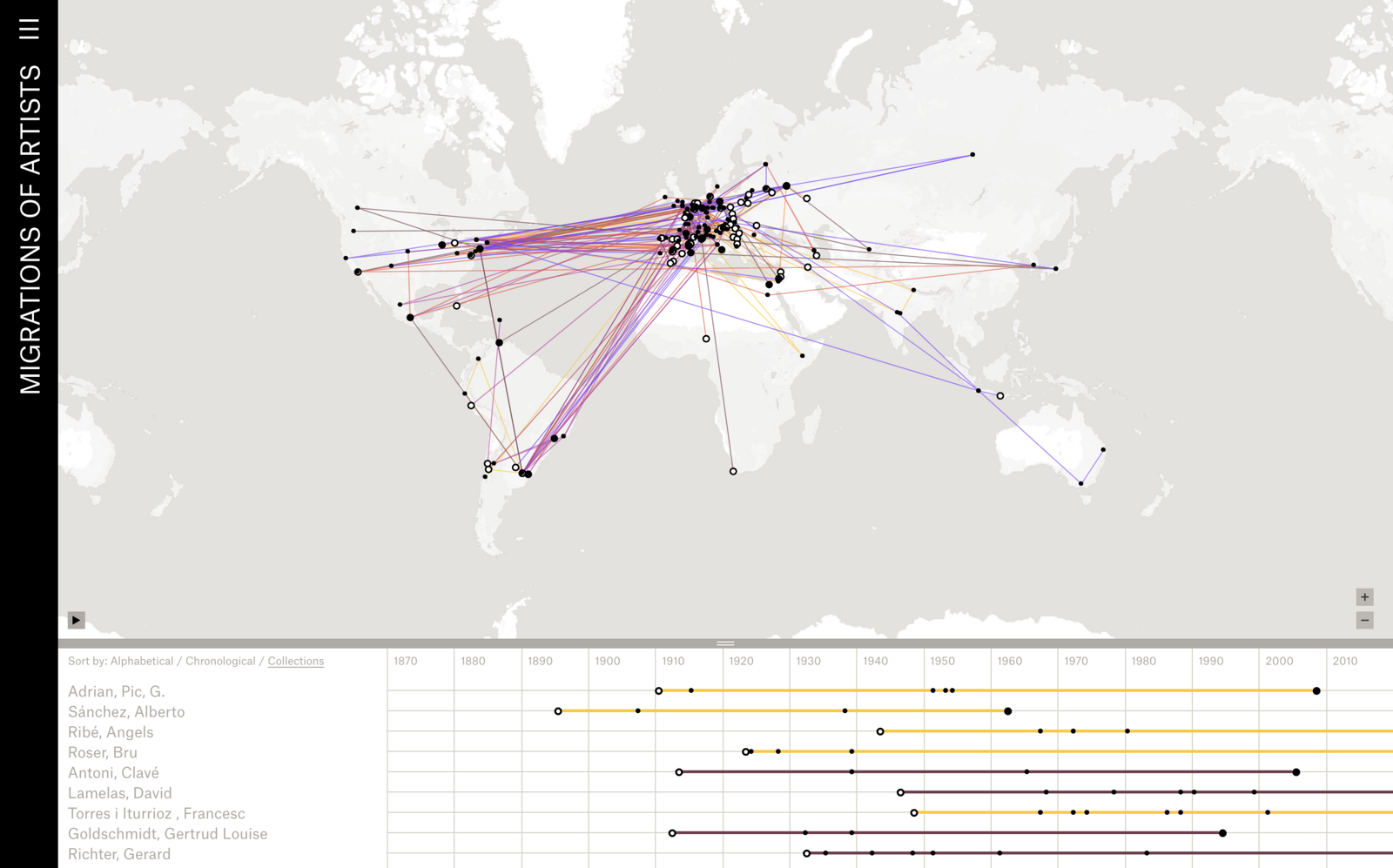

Photo: Michiel Hulshof and Daan Roggeveen.

During a forty-five-minute drive on a six-lane expressway from the center of Lagos to the outskirts, we pass an eclectic mix of buildings, including the Church of God Mission, the Newcastle Hotel, The Peninsula, a shop with “affordable cars,” two Mercedes dealerships, Maldini Marbles, a MegaChicken, a Chinese restaurant, and a Children’s Plaza toy store. Next to the road are massive billboards for Amstel beer (“Toast to Africa’s best’” and a local congregation (“Jesus loves you—Give Him a call on Valentine’s Day”). Below the slogans are informal markets and shops selling construction materials, from wood to plumbing tools. This is a place full of energy, so typical to the many cities in transition we have seen in China.

Finally, we arrive at the entrance of the Lekki Free Trade Zone. The large gate is flanked by two guards wearing AK-47s. On the right is a silver-colored office building, and in front, the flags of Nigeria and China flutter in the wind. Inside is a row of empty desks with signs like “Immigration” and “Customs,” and clocks displaying the current time in London, Lagos, and Beijing. Not unlike a border post.

“The Lekki Free Zone is a new offshore city,” explains Wole Adegoke, the charismatic marketing manager of the Lekki Free Zone Development Company. “It is outside the domain of Nigerian customs. It is a tax-free, duty-free zone where foreign companies can set up shop.”

The zone, located some sixty kilometers from Lagos, is planned to become a safe, green, and spacious satellite city away from the chaos and dangers of Nigeria’s biggest commercial center. Measuring 3,000 hectares, the first phase of the Free Zone will harbor factories, oil processing plants, and other industries, as well as residential areas for approximately 120,000 people and the accompanying hospitals, schools, parks, and churches. The zone is conveniently placed next to the future Lagos international airport and, once finished, will have its own deep-sea port. For when the first phase is successful, another 13,500 hectares of land on the Lekki peninsula is waiting to be developed. Yet beyond the entrance gate, there is still little to be seen of this prosperous future. Half of the Lekki Free Zone currently consists of untouched nature, the other half of vast, empty stretches of yellow sand, poised for development.

The Lekki Free Trade Zone might one day be the center for a prosperous “Made in Africa” industry. At least, that is the hope. Plans to export this particular part of China’s development model have existed for some years. The strategic rationale behind the idea is that overseas SEZs would offer “safe havens” for Chinese companies. By moving production abroad, these companies would be less susceptible to protectionist trade policies against products “made in China.” Furthermore, the model could help underdeveloped countries mirror China’s own economic successes. To that end, in 2006 the Chinese government announced plans to establish around fifty overseas trade and cooperation zones. Three to five of those would be located in Africa. There are currently Chinese zones in Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Mauritius.

These African SEZs represent a Chinese development plan, initiated by the Chinese government, executed by Chinese companies and planned by Chinese urbanists—but on African soil. “Rather than being initiators of this process, African governments are the recipients,” writes Martyn J. Davies, director of the China Africa Network. “China is carving out designated SEZs across the continent. These zones are positioned to become Africa’s new economic growth nodes.”1 In the case of Lekki, it is the China Civil Engineering Corporation which initiated the project. The Chinese developers hold a 60% majority stake in the Lekki Free Zone Development Company (LFZDC), which has a fifty-year lease on the site. The other 40% is in the hands of the Lagos State government.

Almost before we’ve come to a halt, our exuberant guide jumps out of his red Nissan Petrol SUV. “Here,” he signals, crossing the yellow sand to the lake’s edge. “This is the heart of Lekki.” He points to the still-vacant spots where buildings are set to rise in the coming decade: the exhibition center over here, offices there, and houses behind. “It is going to be a masterpiece,” he announces confidently. Omodele Phil Doherty is a talkative business developer for the Lekki Free Zone. It is his job to show potential investors the countless possibilities of the area. “We want to attract investors, bankers and realtors from all over the world. It is not going to be a Chinese city. Not that there would be something wrong with that, but we shouldn’t limit ourselves. It is going to be very international.”

As we continue our tour of the zone, we see blue industrial halls that house the first factories. So far, though, there are no visible signs of the hotly-anticipated economic boom. “There,” says Doherty, directing our gaze. “That piece of land was just sold to a Ukrainian company that makes mayonnaise.” He turns up the volume on the radio, the pop star’s lilting voice breaching the zone’s current, temporary calm: “Girl I want to make you sweat…” As we continue in four-wheel drive over unpaved roads bordered with palm trees, Doherty shouts over the music, “It feels like a safari! Now I’ll take you to the lagoon. You’ll definitely go ‘Wow!’”

Photo: Michiel Hulshof and Daan Roggeveen.

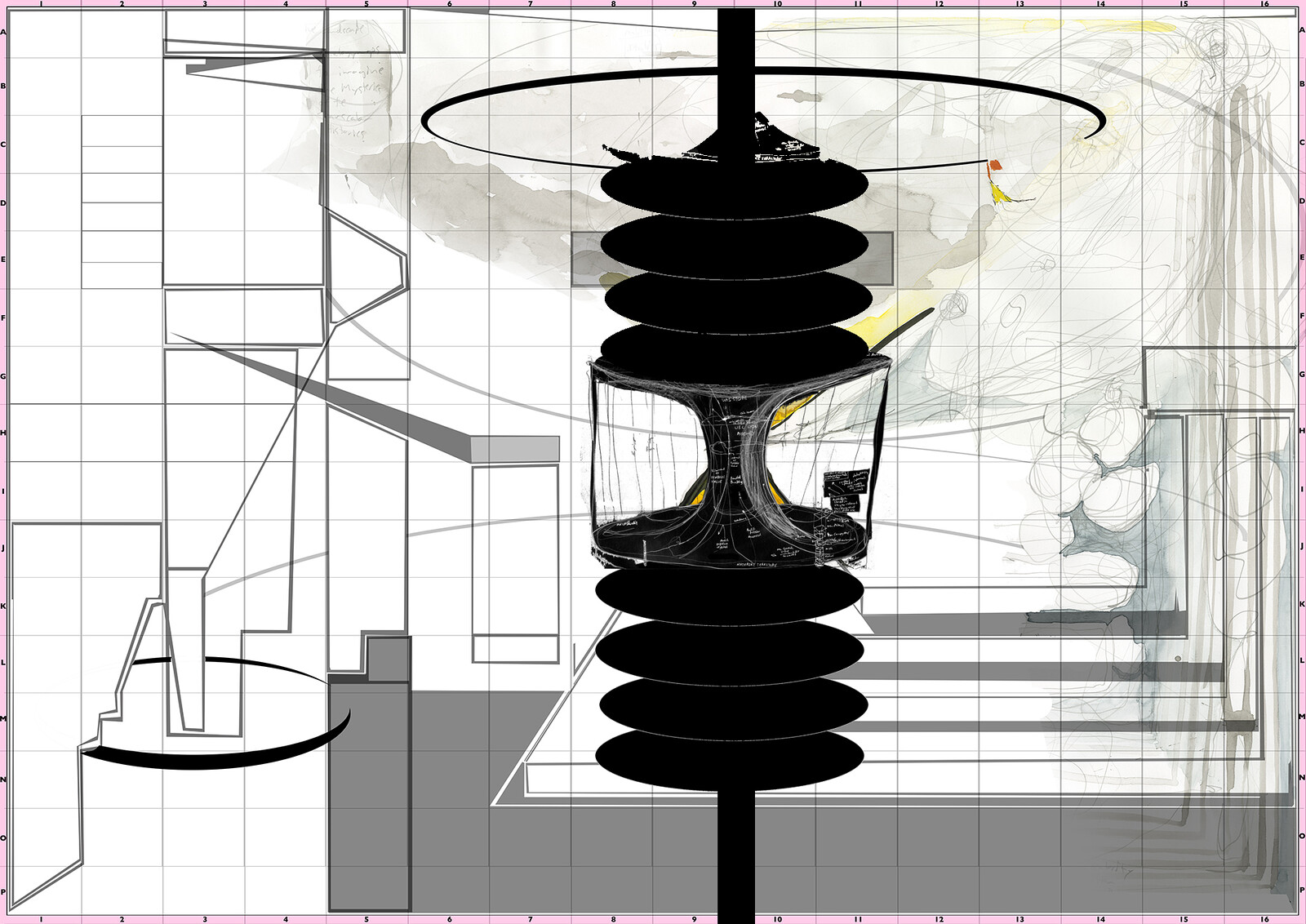

The master plan for the first phase of the Lekki Free Zone is a heavy, solid, A3-sized tome, prepared by the Shanghai Tongji Urban Planning and Design Institute. The design has all the hallmarks of a typical Chinese urban extension plan, with a symmetrical central axis, an exhibition center, large plots with sizable setbacks, and at its heart, a man-made lake. The reference pictures for future buildings are all Chinese. The Lekki Free Zone is completely fenced-off from the rest of Nigeria, meaning residents will live in a gated, privatized city. Workers of the factories inside the zone won’t have that option. For them, designated workers’ accommodation will be erected just outside the gates.

In October 2013, the developers of the Lekki Zone took a flight to the world’s top financial center in search of potential investors. One Wednesday afternoon in the UK capital, the second-floor ballroom of Park Lane’s Four Seasons Hotel welcomed some 300 representatives from London’s fiscal hub, the Square Mile. Mostly men and all dressed almost identically in smart dark suits, the international crowd was engaged in managing private wealth funds. Most were on the look-out for investment opportunities for their African clients in Europe seeking to invest in their home country.

For Mr. Chen Xiaoxing, the Chinese managing director of the Lekki Free Zone Development Company, the principle task was to convince his audience to put their clients’ money on Nigeria. In a speech titled “Lekki, The New Model City,” he laid out key incentives for potential investors. “In the past 100 years,” began Chen in immaculate English, “Africa has missed the tide of industrial revolution. Now there is a new chance.” His presentation sketched Lekki as a city that would not repeat the mistakes of Lagos. Rather, he explained, it would feature better housing, top-notch hospitals and an unprecedented digital infrastructure. Not only would there be a limitation on red tape, the city would also be eco-friendly, and above all, safe.

But will it work? That seems to be the main question that everyone disagrees on. “Please, excuse the mess,” apologizes Dr. Dele Balogun as we enter his admittedly cluttered office. Surrounded by chairs, a fridge, a small television, and shelves groaning under the weight of books and magazines, the University of Lagos economist explains the fundamental problem with Nigeria’s economy of today: almost everything is imported. “Just take a look at me. My suit, my watch, my glasses, my wedding ring, my shoes—they are all imported. If you count it all together, I paid maybe 100,000 Naira for it, of which 80% goes to foreign producers. That means that our need for foreign currency is immense.”

Balogun has strong doubts as to whether the Lekki Free Zone will bring Nigeria the foreign currency he says is needed. “The zone is aimed at selling products on the local market. That means that it will create appendixes of foreign companies. That’s no use to us. We need to turn the system inside out, start producing local products for export.” Fundamentally, says Balogun, the Lekki SEZ is very different from the Shenzhen SEZ. “China started as a socialist planned economy that evolved into state capitalism. Nigeria already has a hedonistic consumer market. You can find the latest model of every product here.”

Not everyone agrees with him. “People are moving to cities, and these people need jobs. They need to be elevated out of informality. They have aspirations. The Free Trade Zone can help a lot,” explains Reinaldo Fiorito, partner at management consultancy firm McKinsey in Lagos, and a supporter of the Lekki zone. According to Fiorito, bankers, manufacturers, government officials, and consultants all expect much from the Lekki project. For backers of the project like him, even if the zone does not immediately bring the millions in foreign investment and the thousands of new manufacturing jobs hoped for, Lekki still represents a new and improved urban model on Nigerian soil. “Currently, the situation in Lagos is a nightmare for business. There are power cuts all the time and traffic is hell. It is time for big and bold solutions. Lekki might be just that.”

If all goes according to plan, the Lekki Free Trade Zone will be a completely gated, privatized city, run by the joint Chinese-Lagos venture. The city can only be entered if you live or work there. Your car will have a tag that identifies you when you go through one of the eleven gates. Inside there will be companies and upper-class people. The zone will be outside Nigerian customs. Consequently, Lekki is planned to become a sort of non-Lagos, having all things Lagos lacks: an accurate transport system, proper drainage, solid spatial regulations, constant power supply, and a reliable police force. At the same time, Lekki will also miss all the elements that make Lagos so exciting: the dynamic environment, the complete mix of people and functions, and the unexpected encounters.

In that sense, the Lekki SEZ is as utopian of an idea as it is dystopian; it considers the existing city as a failure, and creates a new one next to it. In that sense, one could consider the Lekki Free Zone a true export product: that of the Chinese urban model. The phenomena of the twin city is a something that can be seen all over China, most prominently in Shanghai, where the new, spacious, and modern Pudong district was created face to face with the colonial Bund and the chaotic Chinese city behind it.

To see how it all could play out, one only has to take a two-hour drive from the African Union Building in Addis Ababa outside the Ethiopian capital. Suddenly, driving through the underdeveloped countryside, a large gate appears. Above it, in both English and Chinese characters, reads “Eastern Industry Zone.” Upon arrival, we are greeted by the manager of the Hua Jian Shoe Factory, the first company to set up shop in the zone. He takes us inside, and offers an impressive tour. There are massive halls where hundreds of local villagers are working in a modern and clean shoe factory. Along the walls and under the ceilings are red banners with typical Chinese slogans to stimulate workers to do their best. “Late arrival is delay,” says one. But also: “Early arrival is waste.” And: “Those who don’t work hard today, will have a hard time looking for a job tomorrow.”

The workers are Ethiopians. The management is Chinese. The shoes are for Mark Fisher Footwear, an American company. There is a guy from a Brazilian company that does the quality checks. And after the shoes are being packed into cardboard boxes, we learn, they are being shipped to stores all over Europe. Now this is quite something. This might not be a new form of colonialism. This could just very well be the next leap in globalization.

Martyn J. Davies, “Special Economic Zones: China’s Developmental Model Comes to Africa.” In: China Into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence, ed. Robert I. Rotberg (Washington DC: Brookings Institute Press, 2008).

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”

Category

Subject

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”