Contemporary cities, it is argued, are formless, almost like a scrambled egg. They are fragmented collages, transmuting into global or cybercities. Either resilient, sustainable, shrinking, or exploding, they are filled with voids, enclaves, and exclaves. Cities are described as both post-political, entrepreneurial assemblages subjected to managerial authority, and self-organizing complexities, whose vibrant order emerges out of chaos in a dynamic state of mutation, far from equilibrium. They are distributed systems—a mesh of overlapping layers that link across scales from the region to the planet. In short, cities are ensembles of differences.

What if there is another way of thinking about the city of differences? Superimposing the writings of the French philosopher François Laruelle onto those of Rem Koolhaas and AbdulMaliq Simone permits their now-famous musings about the “generic” and the indifference to difference to be evaluated in new ways.1 Can we rethink the complexity of cities and urban dynamics that appear to generate chaos and differentiation, yet simultaneously converge toward a generic condition called the global city?

Thinking Differently

Laruelle calls for a new thought about philosophy: a non-philosophy that sets science or the Real alongside philosophy. “From this place … non-philosophy is able to take philosophy as its raw material, extracting from it various kinds of pure, nonreflected, autonomous, and radically immanent logics… Science is always direct or radical, not reflective or mediated. Science reveals things immediately, unilaterally, and unconditionally.”2

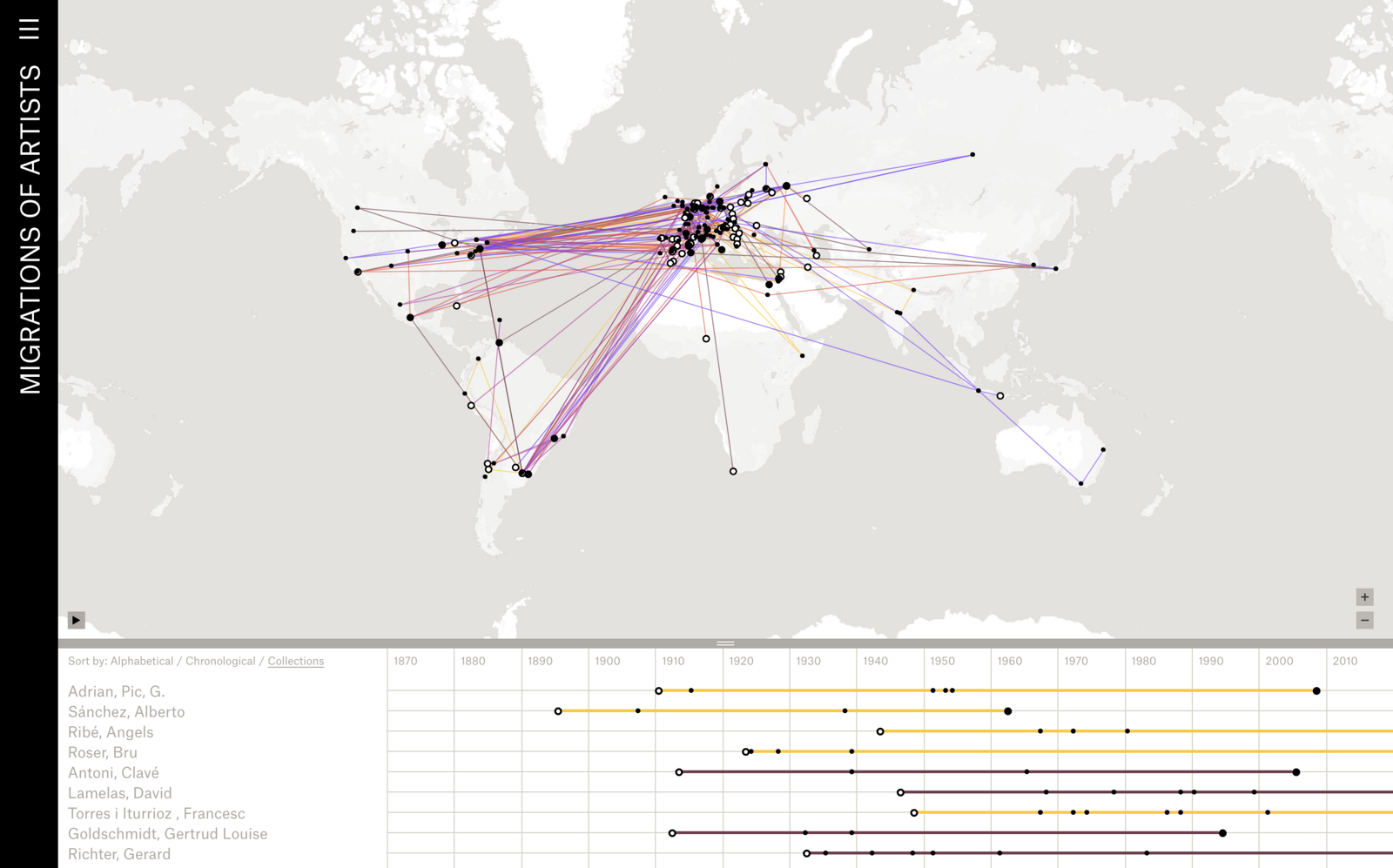

Similarly, Rem Koolhaas calls for a reinvention of urbanism, a staging of uncertainty and an “irrigation of territories with potential” that allow processes to come to life that refuse to be crystallized into definitive form but remain indeterminate and incomplete. Specifically, Koolhaas seeks an urbanism that never suggests it is “new,” but is always about the “more” and the “modified,” adding a temporal dimension to its accounts. The trouble is that all of our analytical models fail to capture these processes, movements, or time. They are either linear (sentences, equations or lines), planar (maps, tables, or diagrams), or three-dimensional (architectural or computer models). Searching for new models and new maps as an alternative to the heaviness of the real construction of the city, Koolhaas seeks “[a]n urbanism that would not necessarily have pretensions toward permanence or stability, a plankton-like urbanism that could infiltrate and invade.”3

Convergence

François Laruelle argues the generic as an entity without attributes is indifferent to difference at the level where all things converge.

Just like a so-called “generic” medicine or product, it [“generic” science and information programming] has lost its most specific, most original point and has become more common and been “marked down.” A dress or vacation package gets “downgraded” when it is no longer original, primary, and unique in its kind, is at a higher and less negotiable cost, is no longer the property of a label or a proper name, but acquires a common value, and when it loses the sufficiency or pretention that could in turn make it “philosophize” or give it “unique” properties, not simply “interesting” but originary and original.4

This commercial model of the generic holds a negative view of an inferior product, a downgrading or subtracting from the original. The “generic” appears once identity is stripped. There is, however, a different regime of the generic, as Laruelle points out: “In the algebraic model of knowledge, the generic is the acquisition of a supplement of universal properties (those of demonstration and manifestation) through a subtraction and an indetermination, a formalization of givens…“5 This “generic” is more universal, more abstract than the elements from which it is subtracted, and hence is indifferent to difference. Therefore, there exist two concepts of the generic: one that is a downgrading or an abasement of its global quality, and another, a global supplement that nevertheless generates or manifests differences.

Similarly, in the opening lines of “The Generic City,” Koolhaas speaks of the generic as a convergence when he asks:

Is it possible to theorize this convergence [this fact that all cities look the same]? … Convergence is possible only at the price of shedding identity. That is usually seen as a loss. But at the scale of which it occurs, it must mean something… What if this seemingly accidental—and usually regretted—homogenization were an intentional process, a conscious movement away from difference toward similarity? What if we are witnessing a global liberation movement: “down with character!” What is left after identity is stripped? The Generic.6

Models, not Theories

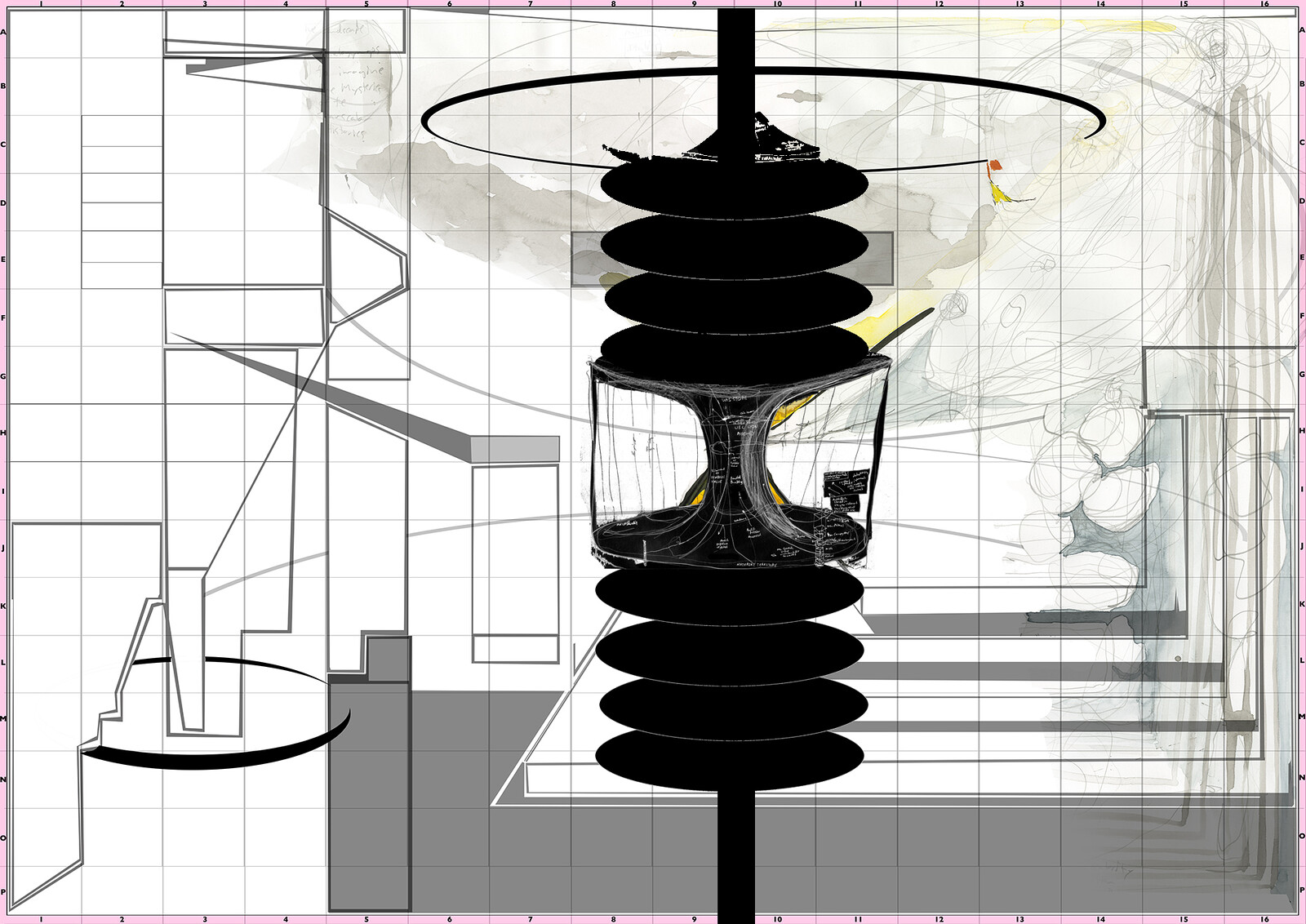

Not prone to offering examples, the closest Laruelle comes to writing about architecture is through a discussion about “engineering which is often identified with design (CAD or CADD).”7 He calls the engineering sciences generic disciplines that treat widely different problems in terms of a project or objective.8 “Thus they articulate multiple levels of ‘concreteness’ and knowledges of different origins: models then become more important than theories in the resolution of problems.”9 Engineers speak about something in general and attempt to sketch out a fictional or information-rich structure of a generic nature including the rules of its functioning. But the sketch and the functions are left indeterminate and open-ended. “The model will always exist in relation to the generic information that it contains and the generic future toward which that information addresses itself and from which the model receives its protocols of transformation as a retooled technology of investigation.”10

Koolhaas works in the opposite direction from Laruelle. His methodology is inductive, moving from the reality of the city of differences to hypothetical generic structures. He writes, “[t]he absence, on the one hand, of plausible, universal doctrines and the presence, on the other of an unprecedented intensity of production have created a unique, wrenching condition: the urban seems to be least understood at the very moment of its apotheosis.”11 Yet according to Koolhaas, the Generic City is an analytical model of invariant structures, which produces unpredictable variations and differences relevant to specific contexts. This appears to be similar to Laruelle’s second definition of the generic. “Each Generic City is a petri dish—or an infinitely patient blackboard on which almost any hypothesis can be ‘proven’ and then erased, never again to reverberate in the minds of its authors or its audience.”12 The Generic City “is fractal, an endless repetition of the same simple structural module;…”13

The Generic City, like a sketch which is never elaborated, is not improved but abandoned. The idea of layering, intensification, completion are alien to it; it has no layers. Its next layer takes place somewhere else, either next door —- that can be the size of a country — or even elsewhere altogether. The archaeologue (=archaeology with more interpretation) of the 20th century needs unlimited plane tickets, not a shovel.14

The Generic Matrix

Laruelle explains that the generic functions as a matrix, or model, within which thought develops. This matrix generates constructed scenarios, or installations pertaining to its empirical conditions.15 Yet these realizations are always unfolding as experimentally open forms. Their results are never predictable.16 Hence the generic model remains indifferent to all potential effects that it might perform.17

Koolhaas defines the “generic city” in the following manner:

The Generic City is the apotheosis of the multiple-choice concept: all boxes crossed, an anthology of all the options. Usually the Generic City has been “planned,” not in the usual sense of some bureaucratic organization controlling its development, but as if various echoes, spores, tropes, seeds fell on the ground randomly as in nature, took hold—exploiting the natural fertility of the terrain—and now form an ensemble: an arbitrary gene pool that sometimes produces amazing results.18

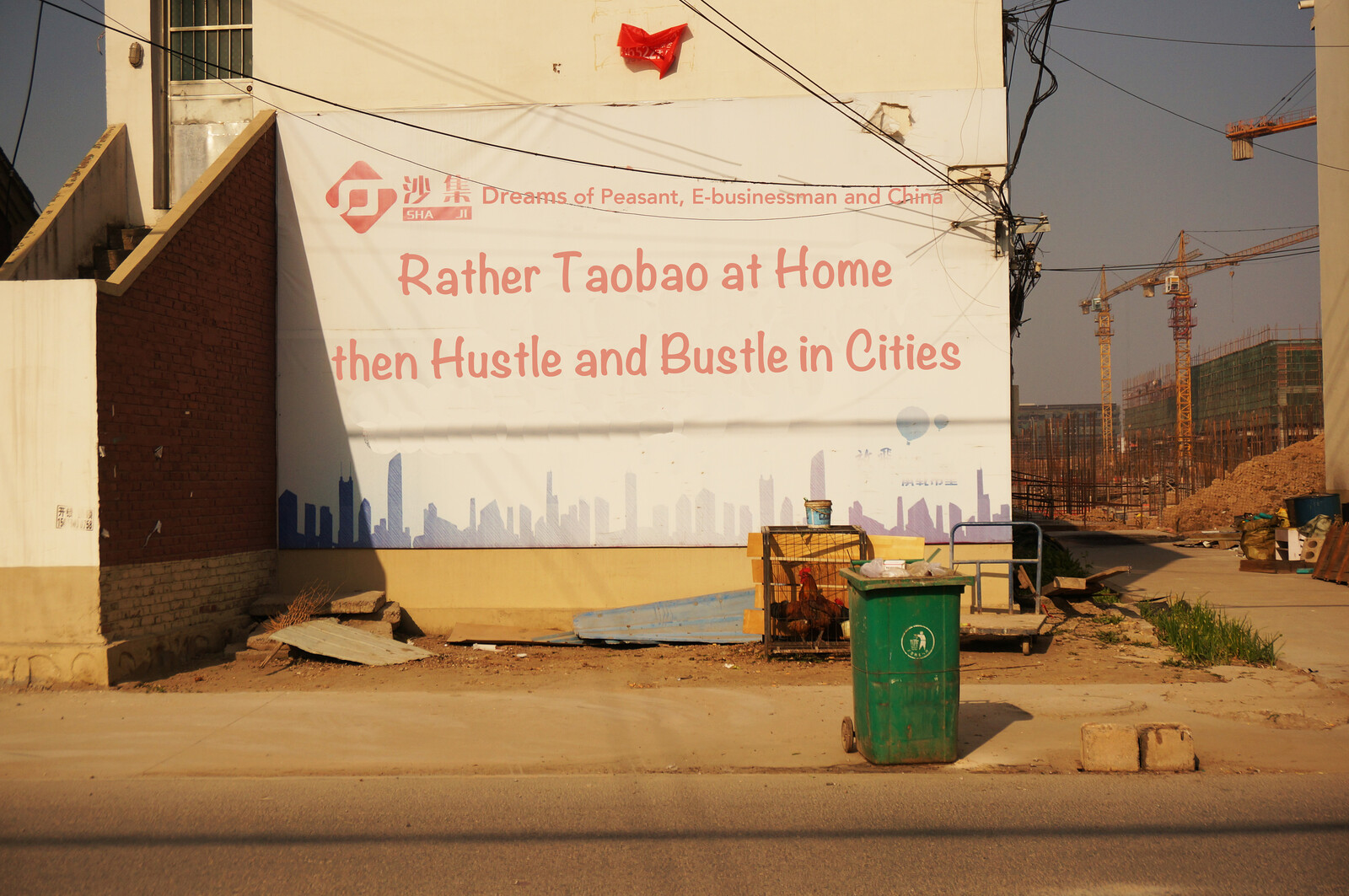

Koolhaas’ multiple-choice image is the matrix of entities that generates unpredictable results. “Variety cannot be boring. Boredom cannot be varied. But the infinite variety of the Generic City comes close, at least, to making variety normal: banalized, in a reversal of expectation, it is repetition that has become unusual, therefore, potentially, daring, exhilarating. But that is for the 21st century.”19

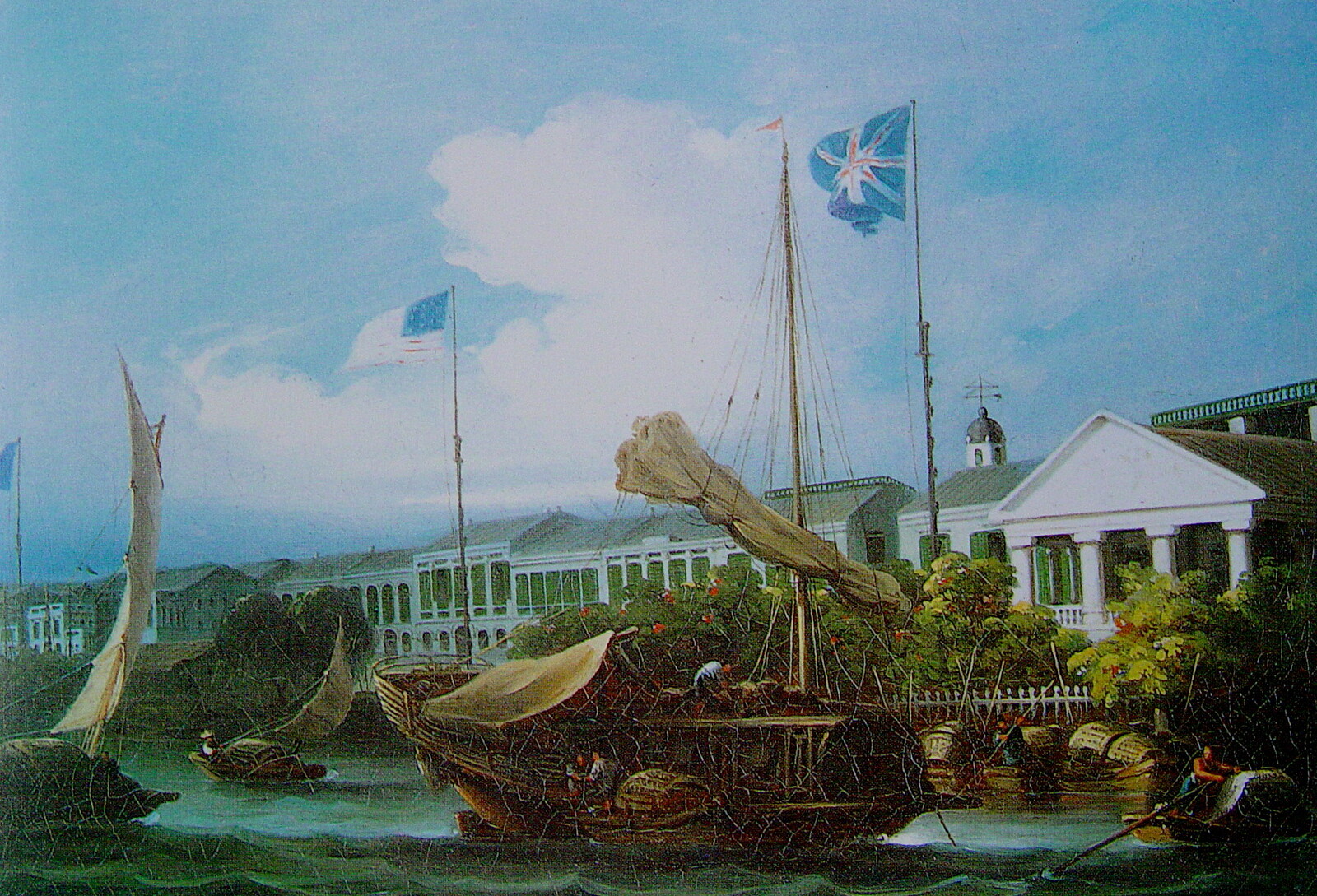

If post-Fordist production is based on the smallest details of difference in order to spike the desire to consume, then maybe repetition, cloning, the indifference to difference is something on which to focus. As Koolhaas and his researchers wrote about Lagos, it may be different, yet the same. That is, Lagos may be the forefront of globalizing modernization, the terminal condition towards which Chicago, London, and Los Angeles are converging. This, they proclaim, is forcing a re-conceptualization of the city. “It is to do away with the inherited notion of the ‘city’ once and for all.”20 There are instead constant mutations and indifferent variations at play (the addition of all options present) according to the operating logics of the generic city where all things are different yet appear the same (the subtraction of the ensemble). An urban dynamic operating on multiple entities and attributes produces invariant structures and common patterns: the giga-factory, the skyscraper, street grids, or parcels of land. These are generic forms that produce indeterminate specifications of difference and innovation in given contexts.

In a similar manner, Jean Attali explains in “The Roman System, or the Generic in All Times and Tenses” how the Generic City conjugates a problem and a solution.

It begins in Rome … as the matrix of the game. The combination of the game and the computer program acknowledges the heuristic power of simulation: the ancient world reinvented on the basis of a series of logos, and reconstructed at the speed of a microprocessor… The planetary distribution of urbanistic models has a quasi-ecological meaning: what flowered in one place will sprout again much further away (in space and time) in a more favorable environment.

The generic models only become real under the local conditions.21

Hence, the city of differences lies in the details of everyday life, in the massive enumerations of bureaucratic datasets, or in the specific installations of its matrix of entities in a given context of space and time. While the generic city lies above these details, it exists across variations and in open-ended modulations. In the generic matrix, details are not analytically connected; they do not add up to the “city.” Instead there is a technology of “thrown togetherness” at play that gives rise to enumerable innovations, experimentations, and unanticipated happenings. That is why the “generic city” and “the city of exacerbated difference” are not contradictory conceptions. At one level, there are differences constantly proliferating, mutating, and deviating: economic, social, cultural, material, geological. Yet at the level of the “generic,” there remain only common invariants and structures.

Push-Back

If the generic matrix generates the city of differences yet remains indifferent to these differences, where lies the ability to resist outside structural invariants and establish an alternative mode of existence? AbdouMaliq Simone, reporting on precarious lives in Africa and Indonesia, sees in Laruelle’s concept of “radical solitude,” also called “radical misfortune,” the potential for the precarious to refuse the determinations imposed on their lives by the capitalist market economy.22 There may be a global scale of urbanism, a series of interoperable standardizations and probabilistic calculations engendered by the property regime of capitalism, yet Simone writes that “endurance for large numbers of urban residents is predicated on indifference to and acts of detachment from prevailing modes of urban power.”23 For Laruelle, “radical misfortune” entails “the solitude of being-foreclosed or separated.”24

Thinking beyond difference, Simone notes that the unruly details of existence generated by indifference actually require opacity, operating in spaces that are largely invisible. In the interstices of the spectacular transformation of cities, lies “generic instability,” generalized precariousness, and expendable lives. Simone labels this “generic blackness.”25 He draws on Laruelle’s notion of rebellion as a generic practice, claiming it as resistance to the foreclosure of the market economy. There is always something that remains as supplement to a city’s convergence toward the generic that cannot be specified or dominated. Simone explains that the property regime “is replete with scams, short-cuts, cost-cutting measures, broken agreements, messed-up contracts, plans gone wrong, and fights within and between municipal and state ministries, architecture firms, consultancies, contractors, property developers, construction firms, infrastructure regimes, planners, local and prospective residents.”26 In these “voids” and interstices of power, between the specifics engendered by the generic, experimentation of the “informal” thrives on indifference.

Simone interprets infrastructure not only as bridges, roads, pipes and wires but also a complex coagulation of finance, labor, and technical specifications that formats space with a variety of use rights and spectacular acquisitions alongside de facto ownership and both unpredictable and illicit uses. The city consequently persists as a gathering of detailed uses in close proximity, yet without communication; a gathering from which nothing can be abstracted.27 In this case, the generic city loses its relational components and enables a plurality of ways of doing things that operate through detachment and indeterminacy.

Simone’s reading of Laruelle sees the generic as “a condition of insufficiency,” residing outside the need to divide the world into existent conditions and uses and then apply planning tools to account for and manage these divisions. Following Laruelle’s suggestions, “[t]he generic refers both to the condition of being ‘anything whatsoever’ and being ‘nothing beyond what one is.’”28 Instead of seeing this insufficiency as subtraction, exclusion, or segregation, Simone suggests that we envision urban space and infrastructure in a different manner. Rather than seeing them as connectors and communicators, he suggests to keep things out of analytical connections and think the potential of the marginal, useless, and anachronistic in new ways. Consequently, precarity holds doom, but also potential.

Conclusion

It appears that anything goes with respect to the abstract matrix of the Generic City. Its urban dynamics call forth unlimited arrays of differences that converge to look all the same. But this sameness, as Tom McGlynn argues in “Toward a Generic Aesthetic,” is more like a container than a category that reduces differences to similarity.29 The generic can house all representations of difference yet be totally undifferentiated, leading to a multiplicity of readings or specificities. For Koolhaas, the form the Generic City takes is shaped by a multitude of these exacerbated differences. For Laruelle, the arrow of interpretation runs in the opposite direction: the generic model is the catalyst for underdetermined and innovative thought across a variety of different domains.30 He calls for a new logic of thought: modeling, engineering, fictioning. We too might think of the logic and models of urbanism in new and different ways.

In general, this essay draws on the superimposition of François Laruelle on the thought of Rem Koolhaas and urbanism made by Jeremy Lecomte, “The Anonymous City: From Modern Standardisation to Generic Models.” (Mphil Cultural Studies Thesis, Goldsmiths University of London, 2014) ➝; and AbdouMaliq Simone and Morten Nielsen, “The Generic City: Examples from Jakarta, Indonesia, and Maputo, Mozambique.” in In Penny Harvey, Casper Bruun Jensen, Atsuro Morita (eds.) Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Routledge Companion, eds. Penny Harvey, Casper Bruun Jensen, and Atsuro Morita (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 128–140.

Alexander R. Galloway Laruelle Against the Digital (Minneeapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), xxiv.

Rem Koolhaas, “Programmatic Lava.” In Rem Koolhaas, OMA, and Bruce Mau, S, M, L. XL, (New York: The Monachelli Press, 1995), 1210.

François Laruelle, “The Generic as Predicate and Constant: Non-Philosophy and Materialism.” In The Speculative Turn, eds. Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman (Melbourne, Australia: re.Press, 2011): 237–256, 238.

Ibid., 239.

Rem Koolhaas, “The Generic City.” In Ibid. Koolhaas, OMA, and Mau, 1248.

François Laruelle Dictionary of Non-philosophy, trans. Taylor Adkins (Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing, 2013), 109.

Ibid., 109.

Ibid., 108–109.

Keith Tilford, “Generalized Transformations and Technologies of Investigation: Laruelle, Art, and the Scientific Model.” In Superpositions: Laruelle and the Humanities, eds. Rocco Gangle and Julius Greve (London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 149–150, 150.

Great Leap Forward: the Harvard Project on the City Volume 1, eds. Rem Koolhaas, et al. (Koln: Taschen, 2001), 27.

Ibid., Koolhaas, “The Generic City,” 1255.

Ibid., 1251.

Ibid., 1263.

François Laruelle, Photofiction, a Non-Standard Aesthetics, trans. Drew S. Burk (Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing, 2012), 23.

Ibid., 78.

Ibid., 3–4.

Ibid. Koolhaas, “The Generic City,” 1253–4.

Ibid., 1262.

Rem Koolhaas, “Lagos.” In Mutations, eds. Rem Koolhaas , Stefano Boeri, Sanford Kwinter, Nadia Tazi, and Hans Ulrich Obrist (Barcelona: Actar, 2001), 650–721, 653.

Jean Attali, “The Roman System, or the Generic in All Times and Tenses.” In Ibid., 20–29, 21.

For “radical solitude,” also known as “radical misfortune,” see Ibid. Laruelle, Dictionary of Non-philosophy, 94–5, 140–141.

AbdouMaliq Simone, “Urbanity and Generic Blackness,” Theory Culture & Society 33, 7–8 (2016), 183–203, 183.

Ibid. Laruelle, Dictionary of Non-philosophy, 95.

Ibid. Simone, 186.

Ibid. Simone, 187.

Ibid. Simone and Nielsen, 128–140.

Ibid. Simone, 188, and Ibid. Simone and Nielsen, 128–140.

Tom McGlynn, “Toward a Generic Aesthetics: A Non-Philosophy of Art, “&&&Journal (May 29, 2015), ➝.

Rocco Gangle and Julius Greve, “Introduction: Superposing Non-Standard Philosophy and Humanities Discourse.” In Ibid. Gangle and Greve, 1–18, 9.

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”