Hospitals are among the least appealing projects for an architect, second, perhaps, only to prisons. The brief of a hospital project is long and complex enough to discourage creativity. Armies of consultants—healthcare planners, medical equipment planners, infection control specialists, wayfinding experts, acoustic consultants, lighting consultants, IT and communications consultants, security consultants, cost consultants—all stand in the way of “frivolous” architectural gestures. After all, lives are at stake. And still, a hospital project is one of the best paid jobs an architect can get. There used to be a time when architects like Otto Wagner, Tony Garnier, Louis Kahn, and Le Corbusier would take on a commission to design a hospital. The latter’s unbuilt Venice Hospital (1965) is probably the last attempt by an avant-gardist to construct a hospital. Since then, hospital design has been relegated to the expertise of a handful of specialized firms that are happy to go about business as usual, which coincidentally or not, often also have expertise in prisons. The architectural standing of hospitals seemed to change during the Covid-19 pandemic, when the future of the hospital became a popular topic in architecture magazines and blogs. Unsolicited proposals for mobile, modular hospitals abounded. A few years later, the question remains unresolved: did this interest mark a turning point, or was it a mere intellectual pastime during a period we would wish to forget?

In 2019, nine months before Covid-19 made the headlines, OMA was commissioned to design a medical masterplan, the Al Daayan Health District, for the state-owned healthcare provider in Qatar, the Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC). The brief was for four hospitals—a tertiary teaching hospital, a women’s hospital, a children’s hospital, and an ambulatory diagnostics center—with a total capacity of 1,200 beds. The plot was 1.3 million square meters of open ground located between Qatar University and the new Lusail City. The ambition was to develop a new hospital typology to better suit local culture, climate, and resources. Like many countries in the region, massive investments in healthcare in recent years had resulted in massive buildings—generic variations of the tower-on-a-podium typology. This typology was initially developed in the West after the Second World War following advances in structural engineering, elevator technology, and HVAC systems, and in response to increasingly scarce land in the city.1 Typically, the podium would contain the emergency department, outpatient, and ancillary services, while the inpatient rooms, surgical suites, and the Intensive Care Units would all be piled up in the tower. Fifty years later, this typology is showing its limitations: too much time is wasted waiting for elevators, there is too much distance between departments, not enough natural light gets into in the podium, it is difficult to adapt the tower layout to single-bed rooms, etc.

Criticism of the tower-on-a-podium typology, also known as matchbox-on-a-muffin, is in fact as old the model itself. In 1970, British architects John Weeks and Gordon Best published a paper titled “Design Strategy for Flexible Health Sciences Facilities.” Citing two studies from a few years before that had measured the growth rate of hospitals, they affirmed:

these two pieces of intelligence confirmed a general view that the traditional basis for hospital design loosely defined as a ‘matchbox on a muffin’ is an incorrect format. So explosive are the forces leading to growth and so all-pervasive are those which lead to change in complex institutions that a traditionally conceived architectural concept of a building fitting closely a particular set of functions cannot have relevance.2

They went on to state that a hospital should not be conceived as a “complete” building and that its future should be left open to as many options as possible. Achieving such openness would require a new design approach starting with the project brief. The brief would have to abandon the convention of describing in detail the client’s requirements, as these would only be valid for a short period of time. However, this would not mean that architecture itself was redundant: “No matter how varied the organizational variation at the micro level, the behavior at the macro level is extremely likely to be predictable,” Weeks and Best concluded.3 They advocated for a maximally “indeterminate architecture”—an architecture that would embrace growth and change rather than fight it.

John Weeks’s architecture firm applied this theory in the project for the Northwick Park Hospital near London, planned in 1962 and opened in 1970. The hospital was designed to be built in stages and extended if needed. However, not all spaces of a hospital have the same need for expansion, Weeks argues. The complex was therefore organized around a more “stable” element—an internal street network—along which “flexible” pavilions would be built over time, and which could be expanded or even demolished. The idea was not new, Weeks admitted; he took inspiration from the Renkioi Hospital in Turkey designed by British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1855 for the British Army during the Crimean War.4 Weeks’s work in turn inspired the Harness hospital system (1973) and the Nucleus hospital program (1975), which aimed to standardize hospital design in the UK.5

Despite Weeks’s theoretical groundwork, Northwick Park Hospital was not a success. The departments that were deemed likely to expand didn’t. The 6.9-meter structural grid impeded the transformation of the inpatient rooms to later standards. The 3.55-meter floor-to-floor height was too low to accommodate new HVAC equipment.6 Thirty years later, the hospital was obsolete, and is now classed as being in urgent need of significant work. Whether or not it can still function as a hospital, or should serve another purpose all together, remains an open question. Much the same fate has afflicted many of the Nucleus hospitals. Their 1,000-square-meter cruciform modules hosting a maximum of 300 beds have been criticized for not leaving enough space for staff.7 The projects fell victim to the very issues that Weeks intended to address. The number of twentieth century hospitals that have already been demolished stand—or, rather, have fallen—as testimony to the fact that, in general, it is now easier to bulldoze a hospital than adapt it to the escalating demands of clinical standards.8

Like Weeks, we have attempted to design a flexible system that can be expanded in the future. We were also inspired by temporary military hospitals, whose flexibility and efficiency far surpass civilian hospitals. Like the architects of the Nucleus hospitals, we have chosen a cruciform module, simply because it’s a basic shape that is easy to “assemble” in large structures. We have sought a solution that could solve immediate problems and should prove flexible enough to accommodate changes unimagined.

Unlike Weeks and the Nucleus hospitals architects, we had plenty of land at our disposal. Our “crosses” measure 4,000 square meters, enough to host either inpatient rooms or clinical facilities. In fact, both share the same module, with the former on the ground floor, in direct contact with the outdoor space. Together, the crosses form courtyards, which have a long history in hospital architecture in the Middle East (such as the Al-Adudi Bimaristan in Baghdad, built in 978; the Nur al-Din Bimaristan in Damascus from 1154; the Al-Mansuri Hospital in Cairo from 1284). The very first permanent hospital in Qatar, Doha State Hospital, designed by British architect John R. Harris in 1957—the first master planner of Dubai—is also built around a central courtyard and remains one of the most appreciated hospitals in the city.

Weeks and his peers were perhaps ahead of their time. Today, digital design and fabrication, building information technology (BIM), advanced materials, robotics, and automation offer the chance to realize longer-lasting, higher-quality prefabricated structures. Al Daayan will be entirely prefabricated. The site will be equipped with a factory that produces all the construction elements for the initial buildings, as well as for future extensions and replacements. It will also recycle what is discarded. Prefabricated, modular structures don’t need to be monotonous and dull. 3D-printed elements produced at the same onsite factory will “decorate” the facades, giving each courtyard its own character. Ornament, vilified ever since Adolf Loos published Ornament and Crime more than one hundred years ago, can now make a comeback without wasting labor or materials.

Qatar has few natural resources. The country is 80% desert and 1.2% arable land, and relies on imports for basic materials, machinery, food, and workers. Relying on global supply chains is risky, as the pandemic made clear when factories shut down, borders closed, flights were cancelled, and ships were stuck offshore. But Qatar had seen a preview of these vulnerabilities when its neighbors imposed a land, sea, and air blockade in 2017 for its ties with Iran. The blockade prompted the country to diversify its economy and strengthen domestic production. Investments were made in vertical farming and greenhouses to reduce reliance on food imports. Likewise, the Al Daayan Health District will include an indoor farm that will produce the food necessary for patients and staff. An increasingly popular solution to providing food for cities worldwide, indoor farms reduce the distance between production and consumption, require less land, have higher crop yield, and use between 75 and 90% less water. Unfortunately, they also use more energy, as much as seven times more than a greenhouse, according to the 2021 Global CEA Census Report.9 But the site will be equipped with its own solar farm covering the rooftops of the buildings in the complex, as well as an energy storage system to guarantee its autonomy in case of emergency. The cooling and heating systems will be integrated to reduce power consumption, using as much waste heat from the cooling system as possible.

Labor is another problem for hospitals, and one that is expected to become more intractable. A hospital needs a significant workforce, and medical personnel are globally in short supply. The World Health Organization estimates that ten million more healthcare workers will be needed in the near term to address the projected shortfall in the sector.10 When we look at the activities that take place in a hospital, a large amount are either routine (appointment scheduling, patient transport, cleaning and disinfection, monitoring, data management, medication dispensing, and supply chain management) or high precision (medical imaging, surgery, drug research), and many can be done without a human touch altogether. But hospitals are still designed as if the non-human element is just an afterthought, an intruder in a space where humans take care of humans. The Al Daayan complex welcomes the robot. Underground, dedicated corridors and elevators, dimensioned according to the devices that use them, form a logistic web that provides each area of the hospital with the supply it needs almost instantaneously. Robotic and human workers coexist in a space conceived for both, freeing the latter from burdens they were not born to bear.

The hospital is where the demands of flexibility, sustainability, and technology converge with unprecedented intensity. Amid geopolitical shifts, pandemics, and climate change, the hospital offers a testing ground for how to design in a fragile and rapidly evolving world. The hospital is again in the position to be at the avant-garde of architecture, not in spite of the extreme complexity that determines its design, but thanks to it.

Cor Wagenaar, Noor Mens, Guru Manja, Colette Niemeijer, and Tom Guthknecht, Hospitals: A Design Manual (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2019), 50.

John Weeks and Gordon Best, “Design Strategy for Flexible Health Sciences Facilities,” Health Services Research 5, no. 3 (Fall 1970): 264.

Weeks and Best, “Design Strategy for Flexible Health Sciences Facilities,” 284.

John Weeks, “Indeterminate Architecture,” Transactions of the Bartlett Society 2 (1964).

Alistair Fair, “Modernization of Our Hospital System: The National Health Service, the Hospital Plan, and the Harness Programme, 1962–77,” Twentieth Century British History 29, no. 4 (December 2018).

William Fawcett, “Simulation: Tools for Planning for Change,” in Healthcare Architecture as Infrastructure, ed. Stephen H. Kendall (London: Routledge, 2018), 146-147.

Jane Smith, “Hospital Building in the NHS: Ideas and Designs II: Harness and Nucleus,” British Medical Journal 289 (December 1984).

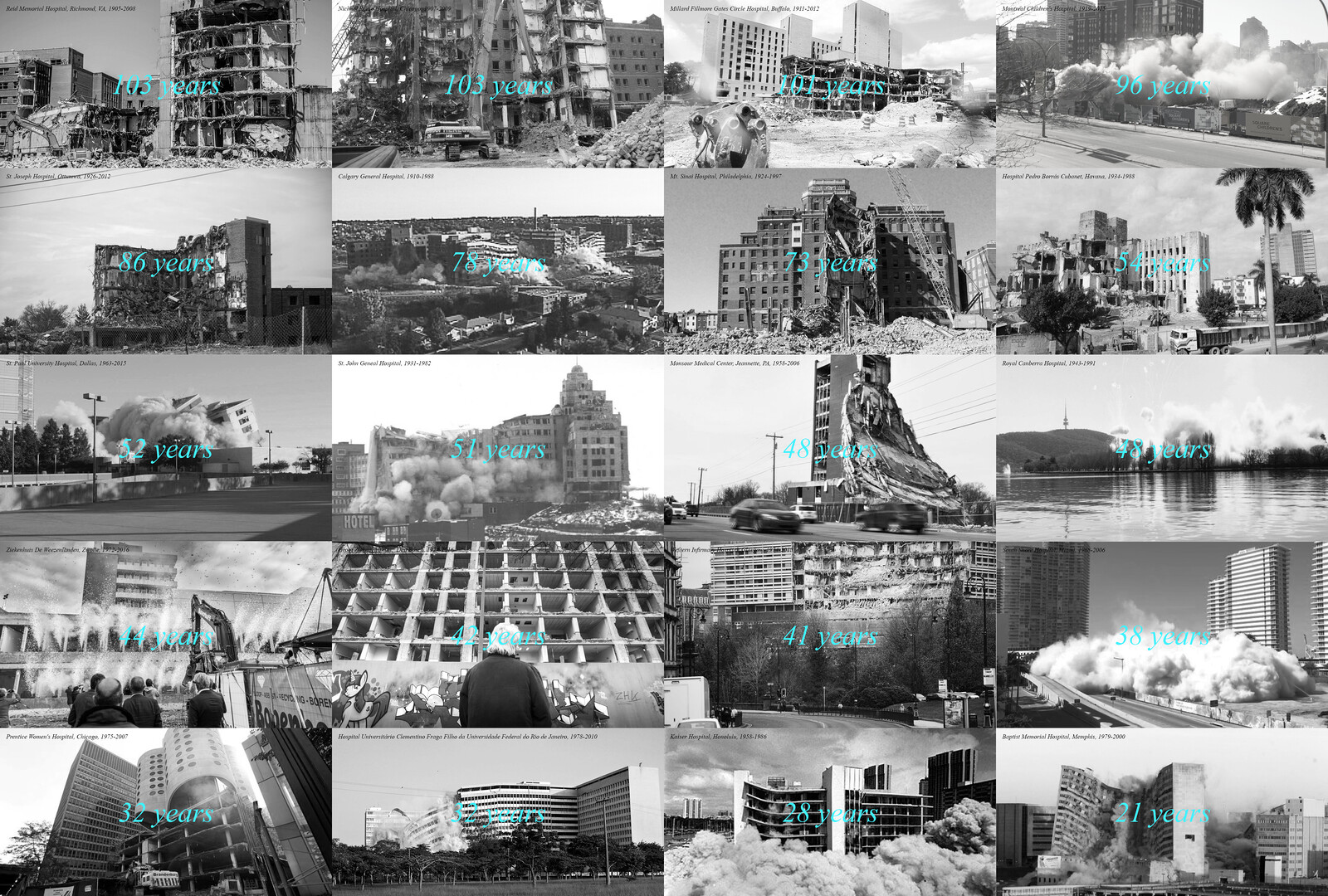

At present, the planning and building of a typical city hospital takes around ten years, significantly longer than it took in 1950. At the same time, the lifecycle of medical equipment is getting shorter. According to the American Hospital Association’s inventory, the lifespan of anesthesia machines and patient-monitoring lifespan is seven years, that of CT scanners, MRI machines, and PET devices, five. This leads to a paradoxical situation; the newer a hospital is, the faster it will be out of date. While the Lariboisière Hospital in Paris built 1853 is still in use, Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, one of the iconic hospitals designed by Bertrand Goldberg, closed in 2011 (and was demolished in 2013), a mere 34 years after it was completed. Here are some further examples: Reid Memorial Hospital, Richmond, IN, 1905–2008 (103 years); Millard Fillmore Gates Circle Hospital, Buffalo, NY, 1911–2012 (101 years); Hôpital Bon-Secours, Metz, Germany, 1919–2012 (93 years); St. Joseph Hospital, Ottumwa, IA, 1926–2012 (86 years); Calgary General Hospital, Calgary, Canada,1910–1988 (78 years); Mt. Sinai Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, 1924–1997 (73 years); Hospital Pedro Borrás Cubanet, Havana, Cuba, 1934–1988 (54 years); St. Paul University Hospital, Dallas, TX, 1963–2015 (52 years); St. John General Hospital, New Brunswick, Canada,1931–1982 (51 years); Monsour Medical Center, Jeannette, PA, 1958–2006 (48 years); Ziekenhuis De Weezenlanden, Zwolle, Netherlands, 1972–2016 (44 years); Groot Ziekengasthuis, Den Bosch, Netherlands, 1974–2016 (42 years); Western Infirmary Hospital, Glasgow, Scotland, 1974–2015 (41 years); South Shore Hospital, Miami, FL, 1968–2006 (38 years); Prentice Women’s Hospital, Chicago, IL, 1975–2011 (36 years).

Agritecture LLC and WayBeyond Ltd, 2021 Global CEA Census Report (2021), ➝.

World Health Organization, “Health Workforce,” 2023, ➝.

Treatment is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich (2021 and 2025), and Istituto Svizzero, Rome (2025).