Treatment returns in collaboration with the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich and Istituto Svizzero, Rome, featuring contributions by Agnes Arnold-Forster, Reinier de Graaf and Alex Retegan, Britta Hentschel, Stanislaus von Moos, Yvan Prkachin, and Lydia Xynogala.

In the mid-twentieth century, answers to the question of what (and whom) hospitals are for would have been self-explanatory. We might once have been able to confidently respond that hospitals are for the sick and for the poor, and that they serve the entire population. But these simple answers have withered with the end of the welfare state, the rise of the pharmacological complex, and the aftershocks of the Covid-19 epidemic. Indeed, the increasing costliness of medical care means the hospital is no longer a safe place to be poor. As a research institution, the hospital is an accumulator of intellectual property as much as a place to seek cure. And, during 2020, temporary hospitals were built precisely in order to protect established institutions from contagious patients.

Yet we still build hospitals. Irrespective of any argument that the institution has changed beyond recognition, the hospital has a firm place in the image of society, as indispensable as the school or the fire station. Hospitals are heavy assets, serious manifestations of political intent as well as money.1 So, suspending for a moment the question of its social function, we might ask the bluntest possible empirical question: what is a hospital? How do we know one when we see one?

The hospital is not a stable architectural type. Unlike many other civic institutions that serve to project the image of society, the hospital is remarkably protean. Hospitals have been an index of social, epistemological, and technical change, and it is perhaps this indexicality that made them early instigators of architectural modernism, as well as what led to their postwar marginalization within architectural discourse. Hospitals are also Janus-faced: even monolithic city hospitals look radically different if you approach the emergency entrance, with its ambulance ramps and stretchers at the ready; or the facade used by convalescing patients, with its planter boxes and manicured sense of calm; or the delivery bay that feeds supplies to—and discretely removes biological material from—what amounts to a busy city factory.

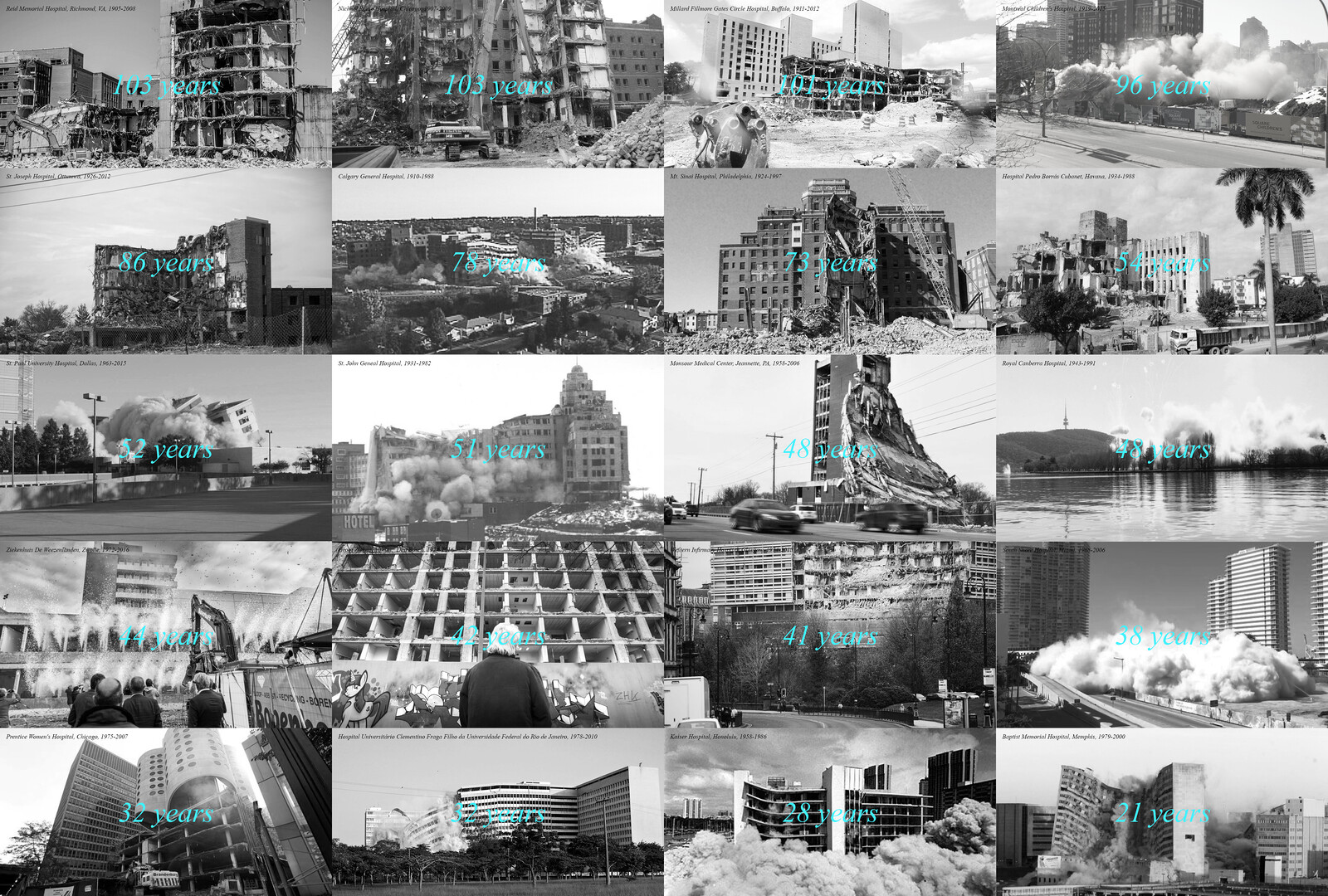

The hospital is perhaps the only object in the built environment whose complexity is as high, if not higher, than the city that contains it. While airports mediate between the scale of a pedestrian and a passenger jet (1:100), hospitals mediate between the scale of a pedestrian and a virus (1,000,000:1). A patient with a complex diagnosis might receive the attention of scores of different specialists and professionals over the course of their treatment.2 And very few hospitals are unified buildings: as the half-life of medical science is far shorter than the half-life of poured concrete, hospitals usually resemble a densely packed campus, with elements of varied age and function drawn together to maximize efficiency and reduce travel time.

The forces that shape the hospital are as heterogenous as hospitals themselves. Insurance policies supply the financial support yet are subject to variability and change; in some regions, insurance has covered psychoanalysis as a treatment for dysmorphia, while, in others, it covers cosmetic surgery. Government regulation operates on hospitals at all scales, from their physical distribution across a territory to the sterilization procedures for surgical instruments. Then there is medical science itself. The discovery of the germ theory of disease radically changed the appearance of the hospital at the end of the nineteenth century, while recent advances in molecular biology have had no less of an influence. The hospital today can be understood not so much as a pillar of the city, but as the most visible piece of a healthcare complex whose real work is conducted as much in office parks and university departments as by bedsides.

The hospital sits in a landscape of regulatory forces that shift, and over time, also shape its appearance. It is an organization that is in perpetual motion, continually physically modified, renovated, and re-branded. On the other hand, for most of us, the hospital is a fixed address of last resort; a place to be born, a place of shelter in times of trauma, a place to die. This might seem like a paradox, but it is precisely because we think of hospitals as indispensable that they will continue to be built in a bewildering array of forms. And, with populations aging globally, there is no doubt that the architecture of the hospital will continue to play a major civic role. Without a consistent and enduring image, hospitals remain challenging for architects to conceptualize. However, architecture itself is not static; its roles are shaped and reshaped by forces and constraints that are navigated in part through the discipline’s reflexive engagement with its own history. Rediscovering that history will therefore be essential for architecture to claim a larger role in the design of healthcare environments.

Conversation between Adam Jasper and Prof. Hong Fung, executive director of CUHK Medical Centre, October 14, 2024, Hong Kong.

Naomi Whitt, Richard Harvey, Garth McLeod, and Stephen Child, “How many health professionals does a patient see during an average hospital stay?,” New Zealand Medical Journal 120, no. 1253 (May 2007): U2517.

Treatment is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich (2021 and 2025), and Istituto Svizzero, Rome (2025).

Category

The editors and authors included in this edition of Treatment participated in two events organized by Istituto Svizzero in Rome and Milan in collaboration with ETH/gta. The event “Transforming Hospital Architecture” (2022) examined the institution from the perspective of the longue durée; “The Hospital Inside Out” (2022) broadened the approach, presenting medical history alongside anthropological and sociological research.