The next time you happen to be in a hospital (hopefully as an observer, rather than as a patient), you will likely find yourself surrounded by machines: X-ray machines, fMRI machines, ultrasounds. The images they make constitute the flashiest products of modern medical knowledge. Yet, alongside these high-technology devices and their entrancing images, more mundane, but often also more consequential, devices reside. If you want to understand the machines that make modern medicine, ignore the flashy image-making devices, and ask to see a blood gas analyzer.

Blood gas analyzers are a ubiquitous, unglamorous technology. Yet their innocuousness belies their transformational importance for hospital medicine, and for the status of the patient and their lungs. The role of the lungs in sustaining life has been known since the seventeenth century, when Robert Boyle determined that air contained a life-sustaining substance. However, despite revolutions in the understanding of lung physiology and the chemistry of gas exchange in the eighteen, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries, this new physiological knowledge provided little in the way of therapeutic benefits. To determine the oxygen and carbon dioxide content of a patient’s blood required mastering complex laboratory procedures, and considerable knowledge of mathematical chemistry. By the 1940s, state of the art techniques in clinical chemistry to determine just what, in fact, was happening within a patient’s blood involved the use of a complex device invented by chemist Donald D. Van Slyke at the Rockefeller Hospital in 1917. The Van Slyke apparatus was accurate and provided valuable information on patients with chronic diseases like diabetes.1 But when faced with acute diseases, like Denmark’s outbreak of polio in the early 1950s, methods like Van Slyke’s were simply too slow.

One of the early ventilated patients during the Copenhagen polio epidemic.

Polio hit the city of Copenhagen hard in 1952. As the epidemic outbreak reached crisis levels, the city’s infectious disease hospital, the Blegdam, was overwhelmed with polio patients suffering from deglutition, struggling to breathe. The subsequent story of the Copenhagen polio epidemic has found its way into the annals of medical history as the birth moment for intensive care. The hospital’s anesthetist, Bjorn Ibsen, adapted an anesthetic procedure for ventilating surgical patients to polio patients; hand ventilation with a bag apparatus and a tracheotomy allowed the patients to breathe without the use of an iron lung (the hospital only had one, which would have been inadequate to the deluge of patients). Through a heroic effort involving over 1,000 medical students, patients were hand-ventilated around the clock, sometimes for weeks. When the dust had settled by January of 1953, it seemed clear that this form of positive pressure ventilation (blowing air directly into the lungs, as opposed to the negative pressure ventilation produced by iron lungs), was vastly superior, and had saved many lives. Ibsen quickly consolidated his achievement in the nearby Copenhagen Kommunenhospital, inaugurating what is often considered the first modern intensive care unit.2

Lost in the heroic narrative of the Copenhagen polio epidemic was a more subtle, but ultimately more profound development in medical technology that occurred behind the scenes. The reason that Ibsen’s intervention had been effective was only partially the transition to positive pressure. Crucial too had been his recognition that patients with polio were not effectively eliminating carbon dioxide from their blood. The hidden character in this aspect of the Copenhagen story was a clinical chemist at the Blegdam, Poul Astrup. Astrup had been able to quickly determine the CO2 content of the polio patient’s blood because he married an ingenious concept—that one could quickly determine the CO2 content of blood by measuring the blood’s pH level—with a remarkable device—a glass electrode that could quickly and accurately determine the pH level of a small amount of blood.3

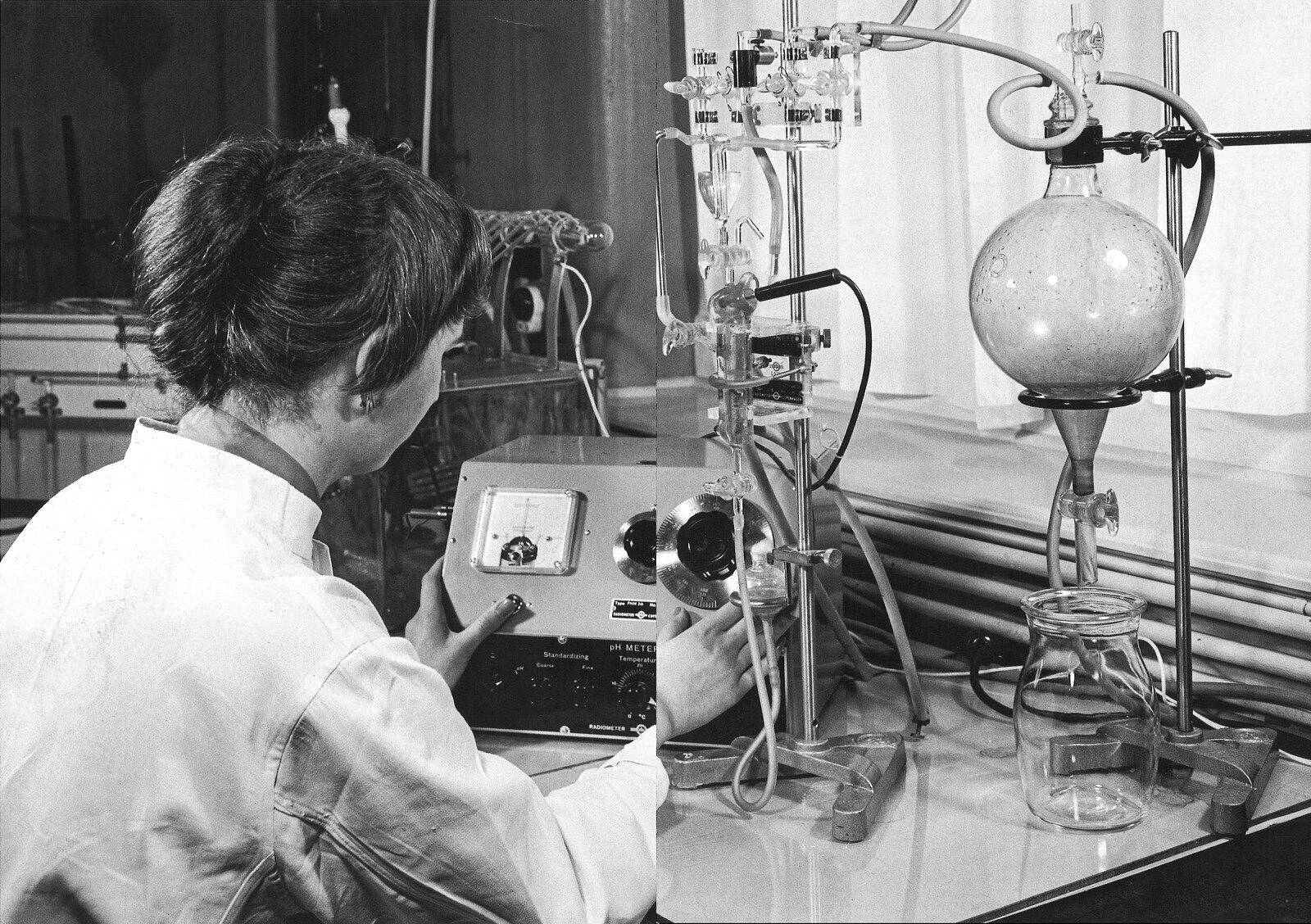

The device that Astrup constructed was a bricolage, as much a reflection of the unusual industrial history of Denmark as of medical necessity. The first blood gas analyzer constructed by Astrup was an amalgamation of two devices: his own design for a special pH electrode, and a commercial pH analyzer produced by the Danish company Radiometer, founded in 1935. The very height of high tech in the 1920s and ’30s, the radio business had been good to Denmark, leading several industrial manufacturers to spin off multiple small firms that each specialized in the production of high-precision scientific instruments. Radiometer was one of these firms, and in the 1930s it found a customer for its precision devices in the Carlsberg Brewery. A brewing powerhouse, Carlsberg had invested heavily in scientific research in the nineteenth century, founding the Carlsberg Research Laboratory in 1875. It was here in 1909 that the lab’s director, S. P. L. Sørensen, introduced the original pH scale, and it was Sørensen who approached Radiometer in 1934 about developing a device to quickly and accurately determine pH from small quantities of liquid. The pH meter developed by Radiometer was a successful product, and when paired with Astrup’s own electrode, allowed for the quick determination of blood CO2. Within a year of the polio epidemic, Astrup approached Radiometer about transforming their improvised apparatus into a marketable medical device. Initially skeptical, Radiometer eventually acquiesced and combined Astrup’s device with additional electrodes developed in the United States that could directly measure O2 and CO2, producing the Astrup-Micro-Equipment 1, or AME1.4

The AME1 might appear to be the most nondescript, uninteresting piece of medical technology ever produced. A hulking piece of metal, canisters, and dials, the AME1 resembles a piece of office furniture more than a precision medical instrument, and its cold, stark design betrays its roots in the radio industry. Yet the single most significant aspect of the AME1 is about as low tech as technology can get: it has wheels. The AME1’s wheels gave it the ability to bring the precision of the laboratory out of the designated hospital lab and into the wards. It also gave the AME1 one of its nicknames in the hospital; the Blodbil (“blood car” in Danish) became a ubiquitous presence in hospitals in Europe and the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, primarily through smart marketing on the part of Radiometer. The Astrup device (as it was also often called) became shorthand for the very idea of blood gas analysis; doctors in this era would often ask that an “Astrup” be performed on their patients.5

The blood car, as much as the physiological insights of the Copenhagen epidemic that spawned it, transformed hospital operations in the next half century. The Astrup device also transformed the underlying conception of lung disorders themselves. The ability to quickly and accurately assess a patient’s O2 and CO2 levels not only turned blood gases into a key diagnostic indicator, but also turned the patient’s lungs into a kind of quasi-cybernetic feedback device. Doctors could quickly determine if their interventions were altering the gas concentration of their patient’s blood—a fact that encouraged therapeutic experimentation. If the blood car had brought the laboratory into the wards, it had also transformed the hospital ward into a kind of physiological laboratory where experiments in treatment could be performed.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of the American physician Thomas Petty. Petty, who pioneered the field of respiratory medicine, was positively entranced by the AME1. “I have a vivid recollection of that Saturday in August of 1964,” Petty recalled, “when I finally mastered the Clark PO2 and Severinghaus CO2 electrodes, which came with my new Radiometer blood gas equipment.”6 Finally, Petty could monitor the effects of his interventions with mechanical ventilators on his patient’s lungs to determine if they were changing the actual gas concentrations of their blood. When paired with a more aggressive ventilator, this resulted in the new clinical syndrome—Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)—discovered (or constructed, depending on your view) by Petty and colleagues in 1967. The defining feature of ARDS was positive response to aggressive ventilation. In other words, if a patient’s O2 levels rose in response to having air blown into their lungs at high pressure, then they had ARDS. The confusion between diagnosis and treatment was only possible because of the rapid analysis of blood gasses enabled by the Astrup, as it transformed lungs into a cyborg-like amalgam of organs and machine systems.7

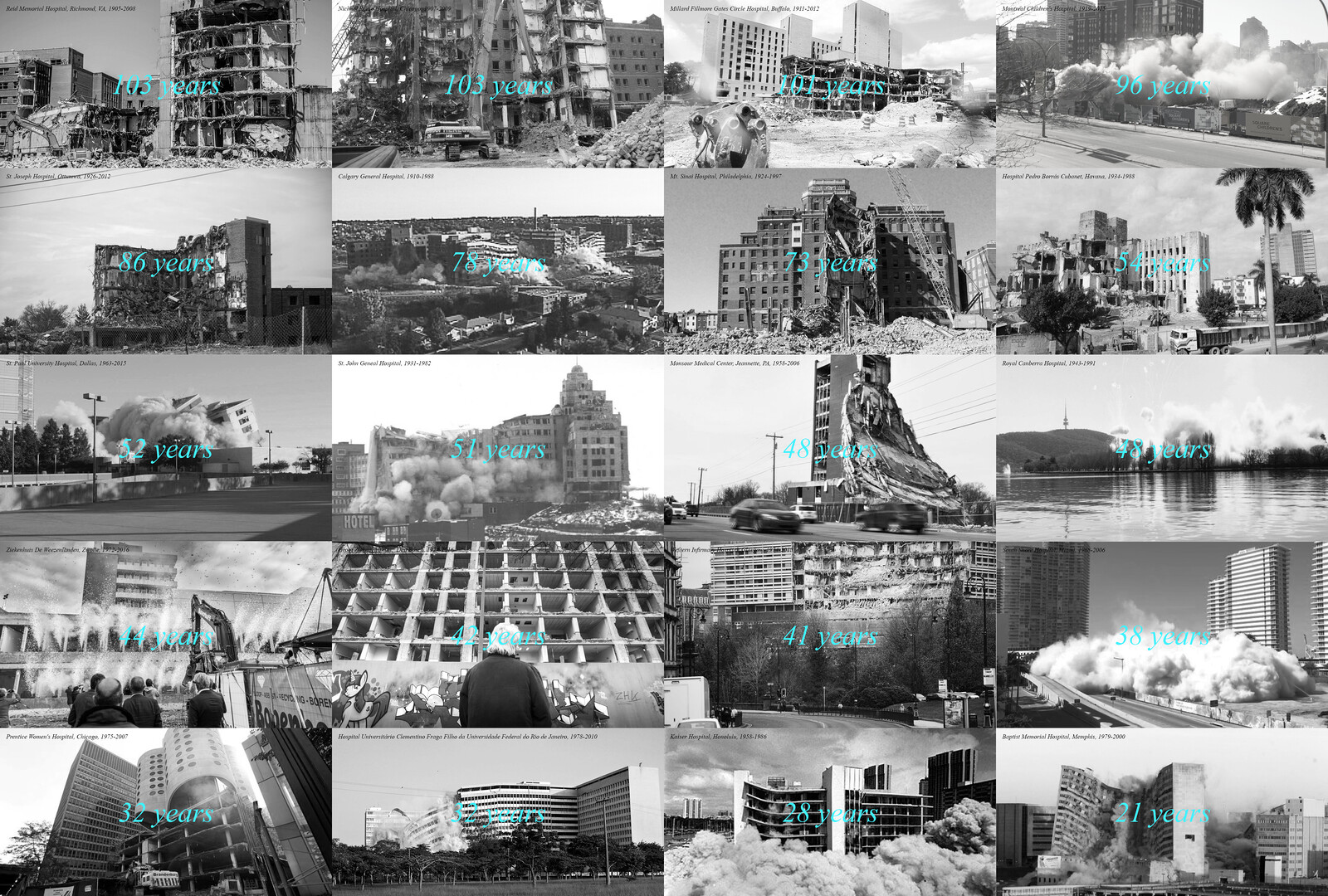

ARDS, and Radiometer, settled into the warp and woof of hospital life in the final third of the twentieth century. Today, Radiometer remains a major manufacturer of blood gas machines for hospitals. Blood gas analysis also transformed Radiometer; in the 1960s, the company lost much of its market for scientific devices and pivoted to focus on the more lucrative medical devices market. In this respect, Radiometer was part of a larger trend, as non-medical industrial and technology firms discovered that there was money to be made in the high technology world of postwar medicine.

ARDS, too, is a regular feature in the hospital, a fact that became particularly important during the early waves of the Covid-19 pandemic, when a diagnosis of ARDS was likely to land a Covid patient on a ventilator. That many of these patients were, in fact, ventilated too early and too aggressively remains an uncomfortable point of discussion among intensive care physicians. Covid produced a rapid drop in O2 levels, a fact easily observed with modern O2 sensors, even if the patient’s lungs remained functional enough to allow for normal breathing. Yet because of the narrow focus on blood gas levels that is a legacy of Radiometer and the AME1, many patients were ventilated unnecessarily, which may have resulted in excessive fatalities.8 In this respect, the AME1 is emblematic of many hospital technologies occupying a complex terrain that encompasses valuable innovation, banal technological ecosystems, and a potential source of iatrogenic injury. As such, unearthing the history of such hospital artifacts is also series of overlapping endeavors, at once in medical history, technological history, and medical practice.

Robert Boyle, The Sceptical Chymist or Chymico-Physical Doubts and Paradoxes. (Oxford: Henry Hall, 1680); Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, Oeuvres de Lavoisier (Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1862); Heinrich Gustav Magnus, “Über das Absorptionsvermögen des Blutes für Sauerstoff,” Annalen der Physik und Chemie 66, no. 10 (1845), 177; Carl Ludwig “Zusammenstellung der Untersuchungen über Blutgase,” Zeitschrift kaiserlich königlich Gesellschaft der Ärzte in Wien 1 (1865), 145; Christian Braunschweig Bohr, “Blutgase und respiratorische Gaswechsel,”in Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen, ed. Wilibald A. Nagel (1905), 54; August Krogh, “On the mechanism of the gas-exchange in the lungs,” Skandinavisches Archiv für Physiologie 23, no. 1(1910): 248–278; Donald D. Van Slyke and James M. O’Neill. “The determination of gases in blood and other solutions by vacuum extraction and manometric measurement,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 61, no. 2 (September 1924): 523.

Louise Reisner-Sénélar, “The Birth of Intensive Care Medicine: Björn Ibsen’s Records,” Intensive Care Medicine 37, no. 7 (July 2011): 1084–86; James Le Fanu, The Rise And Fall Of Modern Medicine (Little, Brown Book Group, 2011), 72–81; Henry Cai Alexander Lassen, Management of Life-Threatening Poliomyelitis, Copenhagen, 1952–1956, with a Survey of Autopsy-Findings in 115 Cases (Edinburgh: Livingstone, 1956).

Lassen, Management of Life-Threatening Poliomyelitis, 111–20; P. Astrup and S. Schrøder, “Apparatus for Anaerobic Determination of the pH of Blood at 38 Degrees Centigrade,” Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 8, no. 1 (January 1, 1956): 30–32; P. Astrup, “A Simple Electrometric Technique for the Determination of Carbon Dioxide Tension in Blood and Plasma, Total Content of Carbon Dioxide in Plasma, and Bicarbonate Content in ‘Separated’ Plasma at a Fixed Carbon Dioxide Tension (40 Mm Hg),” Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 8, no. 1 (January 1, 1956), 33–43.

Hasse Lundgaard Andersen, Livsværk: Radiometer, 1935-2004 (Historika/Gads Forlag, 2020), 12–55.

Andersen, Livsværk, 12–101.

Thomas L. Petty, “In the Cards Was ARDS (How We Discovered the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome),” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 163, no. 3 (March 2001): 62.

Yvan Prkachin, “The Reign of the Ventilator: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, COVID-19, and Technological Imperatives in Intensive Care,” Annals of Internal Medicine 174, no.8 (Aug 2021): 1145–50.

Prkachin, “The Reign of the Ventilator.”

Treatment is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich (2021 and 2025), and Istituto Svizzero, Rome (2025).