De Hogeweyk, in Weesp, the Netherlands, might seem eerily familiar, even if you’ve never been there.1 That is entirely by design. Opened in 2009, the world’s first dementia village seeks to create a nostalgia for somewhere residents may have never been, but have always wanted to call home. Based on the power of architecture to evoke strong memories, De Hogeweyk was designed by Dutch architects Molenaar&Bol&VanDillen (now Buro Kade Architects) to provide a comfortable, safe, and even healing environment for those suffering from the memory loss, personality changes, and impaired reasoning often associated with advanced dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease. De Hogeweyk includes apartments, houses, restaurants, stores, a theater, gardens, and a pedestrian-only street on a 3.7-acre site, just southeast of Amsterdam. Since it opened, 152 dementia patients/residents have called it home, and dozens of dementia villages following the Hogeweyk model have been constructed.

Like a real village, a dementia village is a combination of residential, commercial, and “public” buildings. There are, notably, no buildings dedicated to health or medicine. And like in many dementia villages, a range of house types corresponds to different eras and social classes (for instance, 1950s suburbia, urban apartments, Communist-era housing). Dementia villages are evidence of two historical phenomena significant to the history of architecture. Firstly, the rise of the dementia village illustrates the ongoing power of the “village” trope as a caring environment. Dementia-village architecture draws on the imagery associated with pre-industrial small towns, with pedestrian-friendly circulation, family-centered houses, and shared communal spaces. This same precedent inspired the architects of New Urbanism, whose bucolic new towns portrayed a dream-like, happy place. Secondly, the dementia village showcases an urge to camouflage serious illness by making healthcare environments that look like something else. This same trend is illustrated by hospital design since about 1980, which echoes hotels, shopping malls, and even airports.

Dementia villages are popular subjects on social media, especially Instagram. Instagram post from Architecture & Design Scotland (@arcdessco), September 21, 2018, featuring Hogeweyk, Weesp, by Buro Kade Architects.

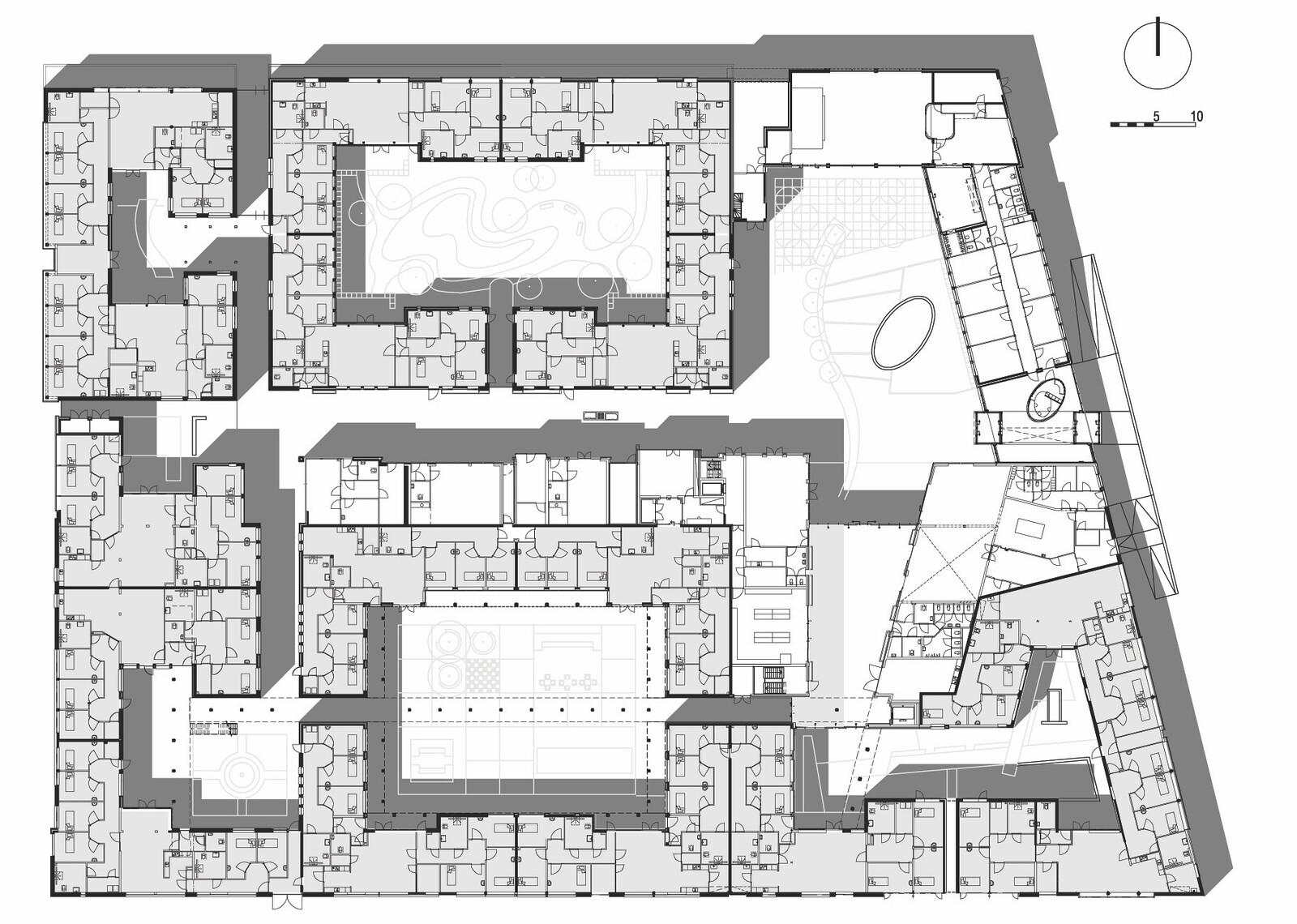

Essential to the way these places work is an impassable surrounding wall with only one entrance. Indeed, the dementia village is a walled, gated community, not unlike a prison in its plan. But while the bird’s eye view might look like jail, inside it’s more of a theater. Economic and social transactions are performed inside. Validation Therapy, a cutting-edge approach to dementia care, “asks us to try to see the world through the eyes—that is, the past life and current experiences, of the elder with dementia. [Hogeweyk] creates an environment that is designed to mask the dementia by pretending that the residents are in an earlier time and place, complete with a non-functional bus stop perhaps to fool the residents into thinking they are free to leave.”2 A social equivalent, for example, might be to not “correct” a dementia patient when they think their late spouse is still alive.

The goal of building a caring environment is a direct counterpoint to the uncaring institution, the traditional nursing home, and its long list of much maligned architectural features—the car-dependent entrance, double-loaded and crowded corridors, identical rooms, enclosed courtyards—and its human counterparts—caregivers dressed in white sporting highly visible medical technologies. The caring village is purposefully anti-medical. That is, medical care is disguised. Just as the architecture is that of assisted living but dressed up as a village, in a caring village, the staff are trained nurses but dressed up as cashiers.

An open secret among anyone who looks closely enough is the close link between De Hogewyck and The Truman Show, the 1998 film starring Jim Carrey about a thirty-year-old insurance salesman who eventually discovers his entire life is actually a television show and that even members of his family are actors. The Truman Show is often cited as a catalyst for reality television, but the central difference that links the show more to a dementia village than to unscripted TV is that Truman knows something is off, but he does not know that he is living within a deception designed to cater to his every whim—as long as that whim does not include leaving. And he does not realize that the entire world is watching him, 24/7.

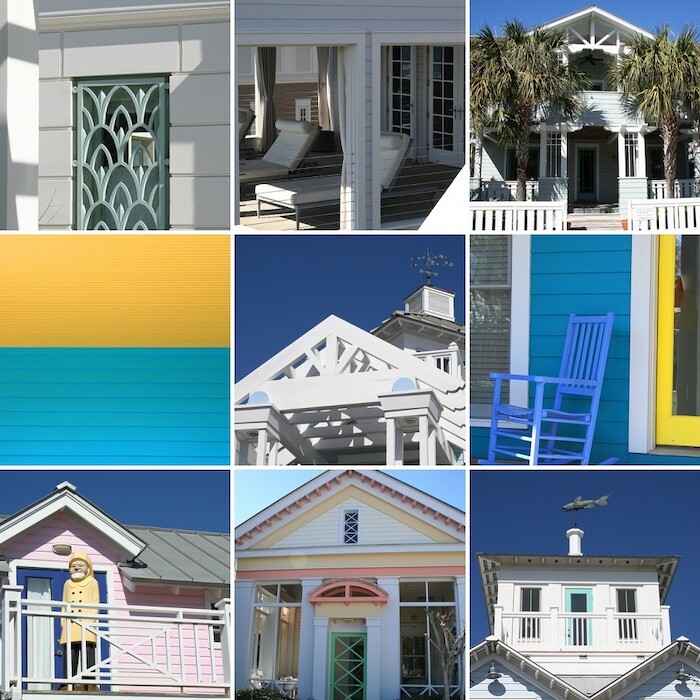

The architecture of Seaside, Florida, emphasizes nostalgic, historical design. Photo by Mary/TheShutterChick, March 16, 2007.

Precedents for dementia villages are the projects of New Urbanism, the popular architectural and urban movement from the 1980s that boasted walkability, detached picturesque houses with porches, and above all happy people. It should come as no surprise, then, that The Truman Show was actually set in Seaside, Florida. Seaside, founded 1982 by the architecture and planning firm Duany Plater-Zyberk + Company, is often considered the premiere example of the movement. These projects are much loved by conservative critics such as Prince Charles and Witold Rybczynski, who originally described it as: “Pretty, picturesque, and romantic, it speaks of summer holidays of days gone by—perhaps not the holidays you actually had at Virginia Beach or on the Jersey shore, but the ones you wish you’d had.”3

Dementia villages are difficult to visit, due to privacy concerns and the exorbitant price of tours. As an alternative research method, we surveyed dozens of websites to find evidence that the dementia village is the most recent iteration of the ongoing belief in the “village” trope as a caring environment. “Village” appears in the names of many of these places, but is also reiterated in its architectural design.

With the tagline, “a place to live your life your way,” Village Langley’s website emphasizes each happy resident’s ability to live an individually meaningful life within a secure environment. The palpable tension between the Sinatra-esque My Way slogan and the appeal to the collectivity of village life is typical of “villages” run by for-profit operators (the cost of residence is C$7,000–9,000 per month).4

Norwegian architects of dementia villages find inspiration in regional, vernacular architecture. Image courtesy of 3RW Architekter, NORD Architects, and NODE.

While Furuset Hagby’s architecture is considerably less contrived than most dementia villages, the “village” rhetoric is loud and clear, in both the language used by the architects to describe their intentions and in the architectural forms. Furuset Hageby is a new housing and treatment center for people with cognitive impairments, focusing on residents and their relatives’ needs, say Bergen-based architects 3rw. It “contains well-known elements from the residents’ everyday life, which serve as a safeguarding and help residents to orientate themselves. It is therefore more demanded that the building does not appear to be an institution, but to a greater extent a small community.”5

The New Vardheim Health Centre in Randaberg illustrates a more direct architectural relationship with real villages. It was inspired by “the old type of Norwegian hamlets called a ‘grend,’ where a small cluster of houses create a micro community.” The “idea of a hamlet where the well-being of home and treatment accommodations of a big institution are mixed, will inspire future institutions,” claim the associated architects 3rw and NORD.6

The village shops in The Grove, Bristol, UK, are often misidentified on social media as Hogeweyk, Weesp. See Instagram post by @Dab4Dementia, July 31, 2016.

There is a constant and implicit tone on village websites and their social media that suggests the small-scale and familial atmosphere of a pre-industrial village is both familiar and achievable today, by design.7 By simulating village architecture—think pitched roofs, winding streets, corner shops—experts believe we can fool patients into feeling better. Even if the forms are parroted, the historic atmosphere and social conditions of pre-industrial villages are gone.

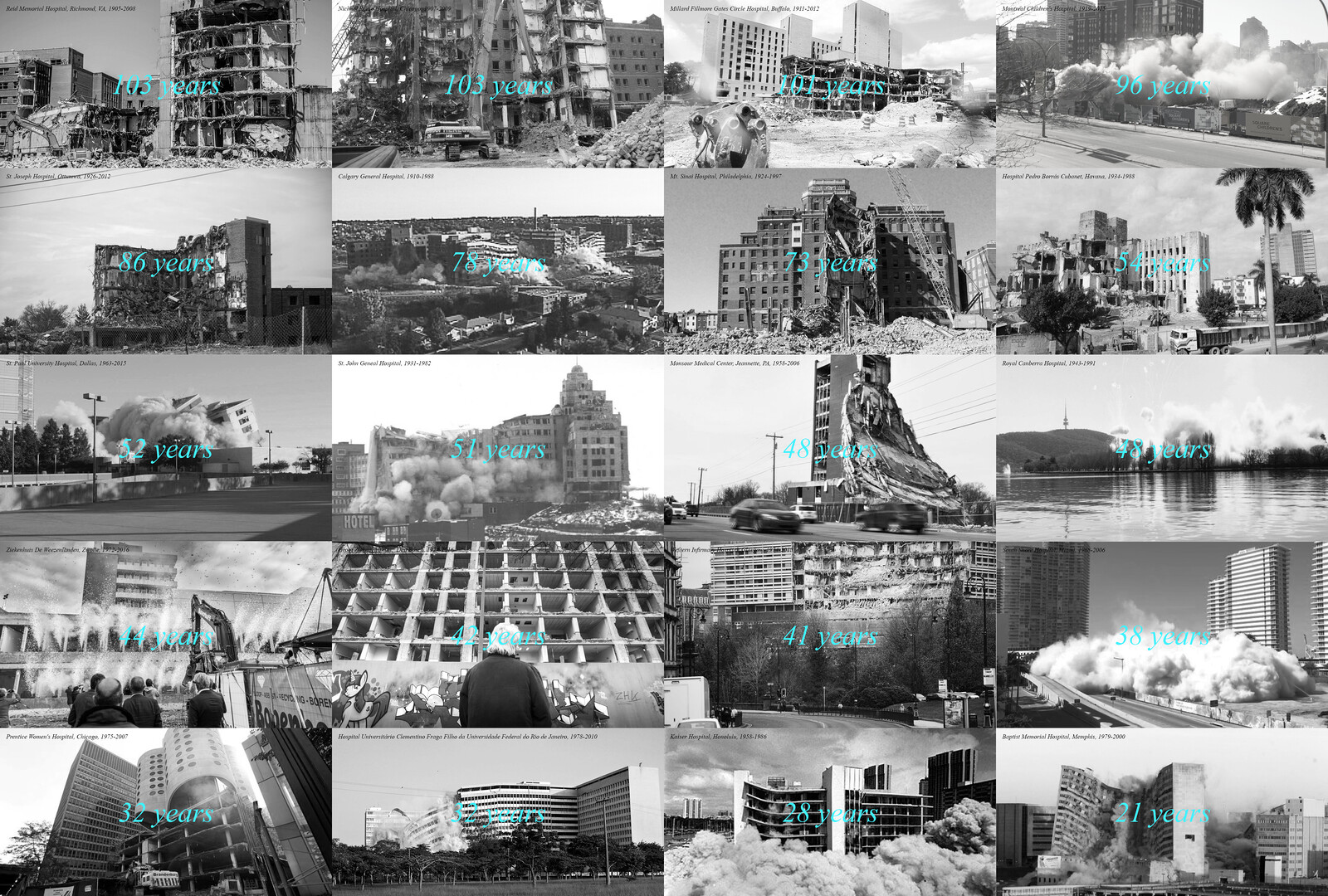

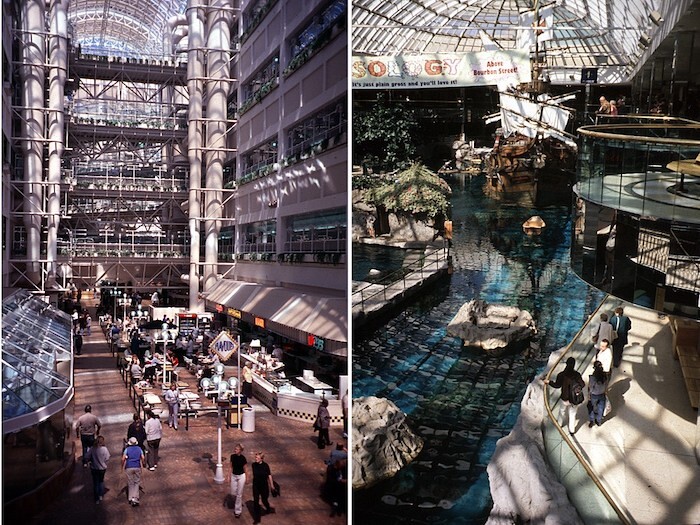

Since about 1980, hospital designers have looked to shopping malls as ways to normalize the hospital experience. Walter C. Mackenzie Health Sciences Centre and nearby West Edmonton Mall, Edmonton, Alberta, photographs by Annmarie Adams.

Acts of Camouflage

The dementia village showcases a wider trend in hospital design over the past forty years: the urge to camouflage serious illness by making healthcare environments that simulate other building types.8 Since the 1980s, hospitals have come to look more and more like shopping malls or airports. Some look like luxury hotels or spas. The Walter Mackenzie Hospital in Edmonton, Alberta, for instance, an early atrium hospital, looks uncannily similar to the nearby West Edmonton Mall, one of the largest malls in North America. While medical historians point to the influence of so-called patient-centered care and the rise of evidence-based design for this hospital trend, the hospital-as-mall is really about normalizing illness. And despite their aesthetic differences, dementia villages are part of this same cultural turn.

A nagging but important question: why these patients and not others? There are a lot of patients who might benefit from better residential care, but it is dementia patients who get these villages. Why not build villages for patients with psychosis, for example, who are also losing touch with reality and cause families a lot of stress? Perhaps it’s because dementia isn’t a condition that medical practitioners currently feel able to treat or reverse, whereas with psychosis, we still hope that the patient will return to reality. To “normalize” the lives of those who are experiencing dementia with architecture is argued to be the best option.9

And to be fair, many residents and their families like living in such places, especially given the alternatives which are too often notably grim. Dutch-born Canadian architectural educator Pieter Sijpkes has two sisters currently living in dementia villages, including one in Hogeweyk. He recounts:

when the Hogewey [sic] option was offered to [his sister] Jannie, her daughters were very happy. And even though they write me that Jannie is “onrustrig” there (meaning not at peace), they are happy they now can sleep at night, knowing she is safe … My visit to Jannie’s place was a very interesting event to me. I had read about Hogewey in the NYTimes, and when I walked in I almost felt I was visiting a celebrity, and I greeted Jannie that way: “Jeez … Jannie, you’re famous!”10

Image from a social media post celebrating the opening of Harmonia Village, describing it as the first dementia village in the United Kingdom. Residents live in converted housing and, unlike in villages such as Hogeweyk, they have access to regular rather than segregated amenities. Instagram post by Hazle McCormack Young LLP (@hmy_llp), February 18, 2020.

The dementia village tells us a lot about ourselves. It tells us that we still see the “village” as a caring environment, despite the fact that few of us have ever lived in villages. It also reveals our deep fear of serious illness, as we engage architecture to simulate or fantasy-based environments. We concur with ethicist Phoebe Friesen, who wrote us: “I can’t quite figure out how I feel about the villages—I think I’m excited and disturbed at the same time. There’s just something so strange about responding to a disorder in which reality is slipping away with more unreality.”11

Finally, the dementia village movement might indicate an important threshold in contemporary design. As architectural historian Martin Bressani has illustrated, all architecture provokes some sort of fictional experience. In his work on Quebec rural churches, Bressani explains: “an architectural setting is the creation of an alternative universe that projects a fictional framework for the institution it houses.”12 While Victorian church architecture projected such “world-making capacity” through its elaborate ornamentation and symbolism, today’s dementia villages do so by offering residents the delusion that they are living normally.

In a true fictional experience, we know that we exist in two worlds at once: the real world in which we exist, and the fictional one we enact (through architecture, books, film, music, etc.).13 But unlike Bressani’s church goers, the residents of the dementia village know only one world. Architecture for dementia indicates where fictional experiences cross a line into another state, where there is no longer an awareness of enacting a fiction. In the dementia village, it’s all enactment.

This paper was delivered at the annual meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians, 2020. Thanks to session chairs Anna Andrzejewski and Willa Granger for insightful comments, incorporated here, as well as to Laura O’Brien who helped with this research in summer 2019. Fiona Kenney and Cigdem Talu helped to revise it for publication. Basem Eid Mohamed and Pieter Sijpkes helped behind the scenes. Bio-medical ethicists Phoebe Friesen and Monique Lanoix also provided helpful remarks. Adams, Chivers, and Lanoix met as co-investigators in the SSHRC-funded project, “Re-imagining Long-Term Residential Care: An International Study of Promising Practices,” PI Pat Armstrong, York University, and have co-published three journal articles.

Peter J. Whitehouse, “Long-Term Care for the Future: Just What is Real Anyway?” in Care Home Stories: Aging, Disability, and Long-Term Residential Care, eds. Sally Chivers and Ulla Kriebernegg (London: Transcript Verlag, 2017), 107.

Witold Rybczynski, “Seaside Revisited,” Slate, February 28, 2007, ➝.

Average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Langley currently is about 1,200 Canadian dollars; long-term care costs in British Columbia top out at about C$2,200.

“Furuset Hageby,” 3RW Arkitekter, 2018, ➝. Thanks to Erika Brandl Mouton at 3RW.

“Sunnhetsgrenden Vardheim,” 3RW Arkitekter, ➝.

“68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN,” United Nations, May 16, 2018, ➝.

One example is Annmarie Adams et al., “Kids in the atrium: Comparing architectural intentions and children’s experiences in a pediatric hospital lobby,” Social Science & Medicine 70, no. 5 (2010): 658–667.

We are grateful to Phoebe Friesen for this insight.

Pieter Sijpkes, email to Annmarie Adams, February 25, 2020.

Phoebe Friesen, email to Annmarie Adams, March 2, 2020.

Translated by Adams with Martin Bressani’s approval, from Martin Bressani and Marc Grignon, “Une protection spéciale du ciel: le décor de l’église de Saint-Joachim et les tribulations de l’Église catholique québécoise au début du XIXe siècle,” Journal of Canadian Art History 29 (2008): 8–49.

Sijpkes’s personal experience confirms this. Describing a visit to Hogewey: “I sat in a very nice bar on a covered terrace in the Hogewey compound…sipping a glass of wine I observed several ‘inmates’ making their rounds. Very different routines…very odd behavior, and I could not help thinking about the movie The Truman Show with Jim Carrey…except that there were no scripts followed here.” Personal correspondence with author, February 25, 2020.

Treatment is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich (2021 and 2025), and Istituto Svizzero, Rome (2025).