When scholars first charted the nineteenth-century “invention” of the modern hospital around a half century ago, they posited a crucial change: a shift from care to cure. Hospitals transformed from charitable institutions caring for the sick poor to institutions devoted to the cure of diseases through clinical science accessible to all citizens. Social historians of medicine including Charles Rosenberg, Janet Golden, and Roy Porter, established an inventory of exciting historical developments related to how the hospital became tied to the university. They noted the rise of aseptic surgery; the provision of trained nurses; the incorporation of bacteriology; the use of modern business accounting; and the stipulation of university-based education for doctors. The modern hospital, they showed, was dedicated to curing the sick.1

Healthcare reformers today want to reverse that history. They advocate a shift from cure to care. They study the “death” of the “sick role” model—illness as both social and biological—due to the birth of the healthcare consumer. Biomedicine today moves away from the biosocial—characterized by the social determinants of health—towards the biocultural—characterized by biopolitics: chronic disease, risk assessment, and computer-based diagnosis. In spelling out such tensions between medicine and culture, scholars have staged new ethical concerns.2 To keep advancing, the argument goes, we need a new ethics of care. Hospital medicine must change. And yet, a new ethics of care, however powerful, is unlikely to transform hospital architecture.

The causes and effects of hospital activities on hospital architecture are not exhaustively catalogued through considerations of care and cure. Cure has empirical evidence. We audit data for surgical outcomes, track the reduction in death rates for childhood leukemia, and estimate lives saved due to antiretroviral therapy for HIV patients. Care, conversely, is relational. It calls for collaboration and emotional judgement. What concepts of care could interrogate how hospital architecture interacts—or should interact—with the psychosocial dynamics and practicalities of illness? The question becomes even more daunting, perhaps logically inconsequent, when we acknowledge that the hospital serves many primary social roles, such as medical education, beyond the clinical encounter.

Nurses are key to hospital care. In her benchmark history of modern American nursing Ordered to Care, Susan Reverby explored three ways in which nurses have been ordered to care: vocation, labor, and architecture.3 Nurses were historically often members of religious orders with a vocation to care for patients; they were commanded to care for patients as part of their job; and the hospital was put in order in such a way that the nurses could care for patients efficiently. Medicine discusses transformations in hospital design as if the aim is to improve the clinical encounter between doctor and patient. But history tells us that improvements are aimed at optimizing these types of nursing care.4

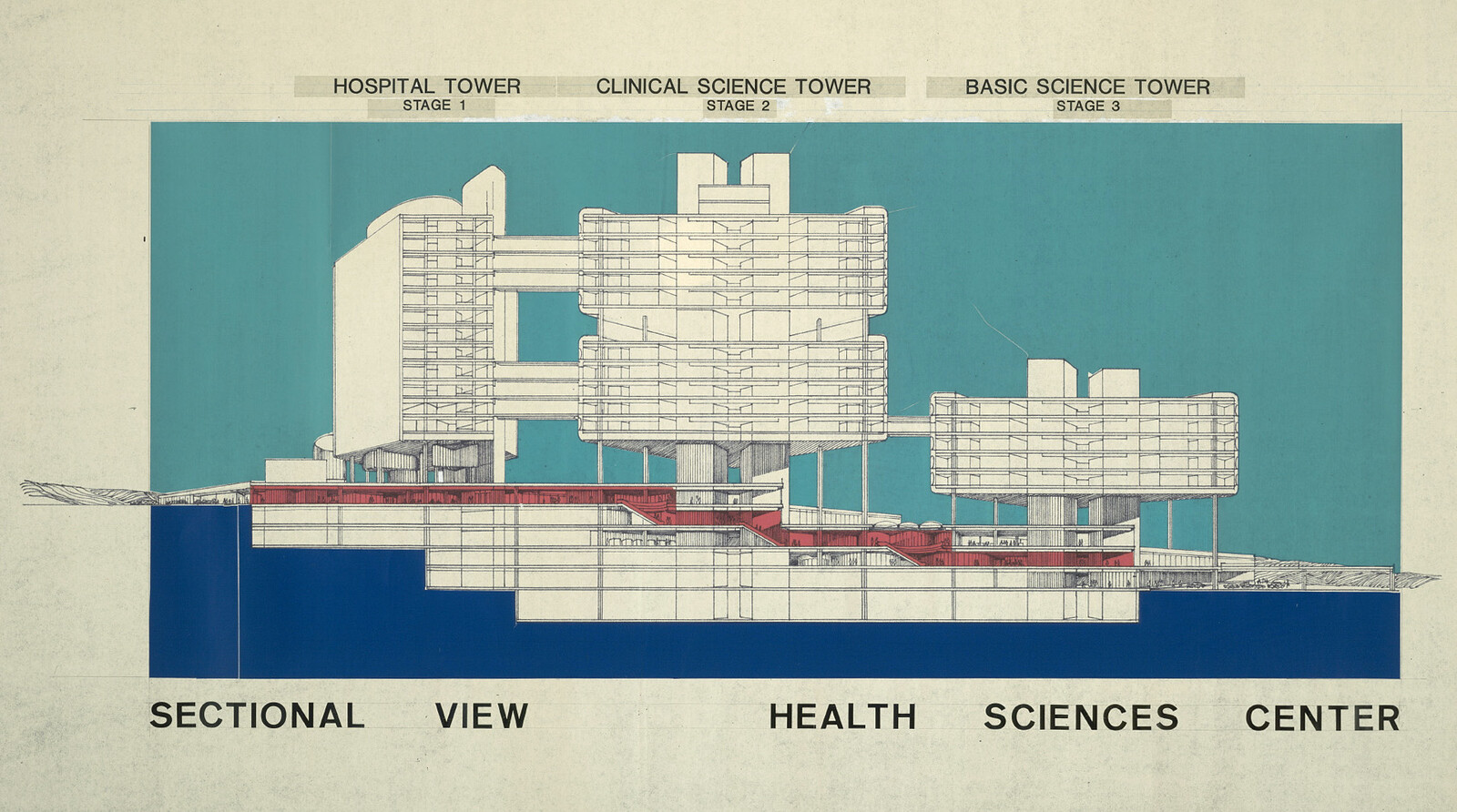

History also shows that modern hospital architecture has three beginnings. Michel Foucault and his colleagues documented a sea-change in hospital architecture around 1770.5 They argued that in pre-revolutionary France, illness emerged as a spatial problem. Hospital designers—architects, doctors, and city administrators—used hospital form to probe new organizational systems for governing populations. A century later, around 1870, the so-called invention of the modern hospital provoked designers to both expand and divide up the building. Architects now provided rooms for emerging technology (such as X-ray imaging), experimental practices (such as trauma surgery), ascendant social groups (the middle class), and new employee categories (laboratory technicians). Later, after World War II, impelled by expansive government funding programs across the West such as Medicare, reformers pushed architectural design to engage computation, the automobile, and the specter of obsolescence. Now known as the “health sciences center” or the “health campus,” today’s hospital is that third modern hospital, re-invented and re-formed around 1970.6

Could a shift from care to cure account for these three eras of the modern hospital and three paradigms of medicine? Scholars argue that changes in medical practice precede and cause all changes in hospital architecture. Already in 1988, sociologist Lindsay Prior vigorously argued an inextricable connection between medical theory and medical architecture.7 In 2016, historian Jeanne Kisacky assessed the impact of the rise of the germ theory on the rise of the American hospital, literally: after the ascendance of the germ theory around the First World War, vertical, multistory hospitals rose up in American cities.8 For these analysts, form follows medicine.

This claim that medical practice conditions medical architecture, however, is difficult to substantiate. Medical practices are internal to hospital life. Yet external factors have clearly driven design choices. The Second Industrial Revolution produced railways, telegrams, radio, and electrification, as well as iron, steel, plate glass, elevators, and petroleum. Understanding hospital architecture means understanding the effects of such techno-social change. The building type also tracks disciplinary change. Historian Annmarie Adams has shown that hospital design closely follows architectural trends and social flux.9 In the 1920s, for example, American hospitals adopted the look and conveniences of modern hotels in order to accommodate middle-class patients; in the 1980s, they adopted the food courts, parking lots, and glass-roofed atriums of shopping malls to accommodate suburban patients.10

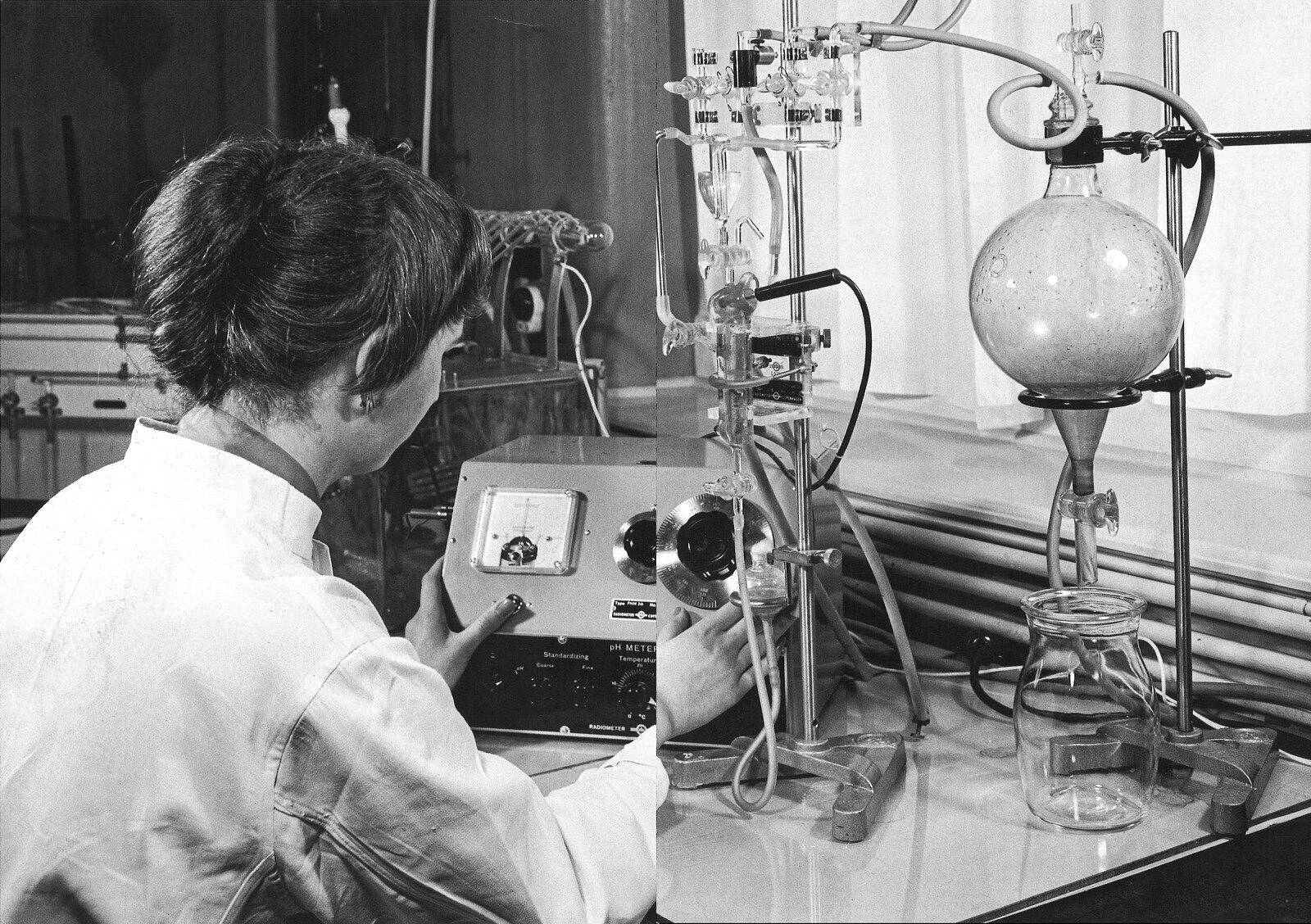

Technology can also be a driving force for architectural change in hospital design. In the 1950s, Canadian hospital consultant Gordon A. Friesen proselytized for automation.11 Careful implementation of technology, he argued—elevators, dumbwaiters, material processing centers, automated delivery carts—would help nurses deliver what he called patient-centered care.

Technological modernism produces detractors. The new version of patient-or family-centered care promulgated today, however, is often anti-technology, with an implicit judgement that hospitals are overwhelming, both architecturally and technologically. For most people, the techno-social determinism of the modern hospital, often misidentified as functionalism, is dehumanizing. Non-architects have pushed back against the technological modernity of the modern hospital. Frequently, they identify technology as scourge, exemplified in a famous skit from British comedy troupe Monty Python’s Flying Circus that shows patients, doctors, and administrators baffled, intimidated, and overwhelmed by blinking, beeping, buzzing—but still somehow useless—machines.

In all three eras, architects mooted strategies to combat the dehumanizing effects of the machine-hospital. They suggested flexible, column-free structures that allowed for construction to begin before floor layouts were confirmed. Interstitial mechanical floors allowed rapid changes to layouts after construction. Designers proposed so-called “healing gardens,” based on the conviction that there is a basic human (“biophilic”) correspondence between healing and plant life. They included those atriums as wayfinding devices and to recall the suburban environments familiar to their users—patients, visitors, and staff all enjoy having Burger King onsite.

Both architects and non-architects have proposed architectural values not captured by medicine, technology, and philanthropy. For instance, the modern hospital serves as repository for art and for its related activities: advising, buying, collecting, donating. Hospitals must accommodate those practices in addition to—and sometimes instead of—caring or curing. Henri Labrouste, architect of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, speculated that “If I were to make a hospital, I would put paintings in all the rooms.”12 Since then, an industry has grown up around art in hospitals. Environmental psychologists, among others, continue to argue that art contributes to both care and cure. Yet artwork in hospitals rarely indicates a shift from one mode to the other. It highlights important social, cultural roles for hospitals other than attending to patients: charity, civicism, cultural expression, economic development, and so on.

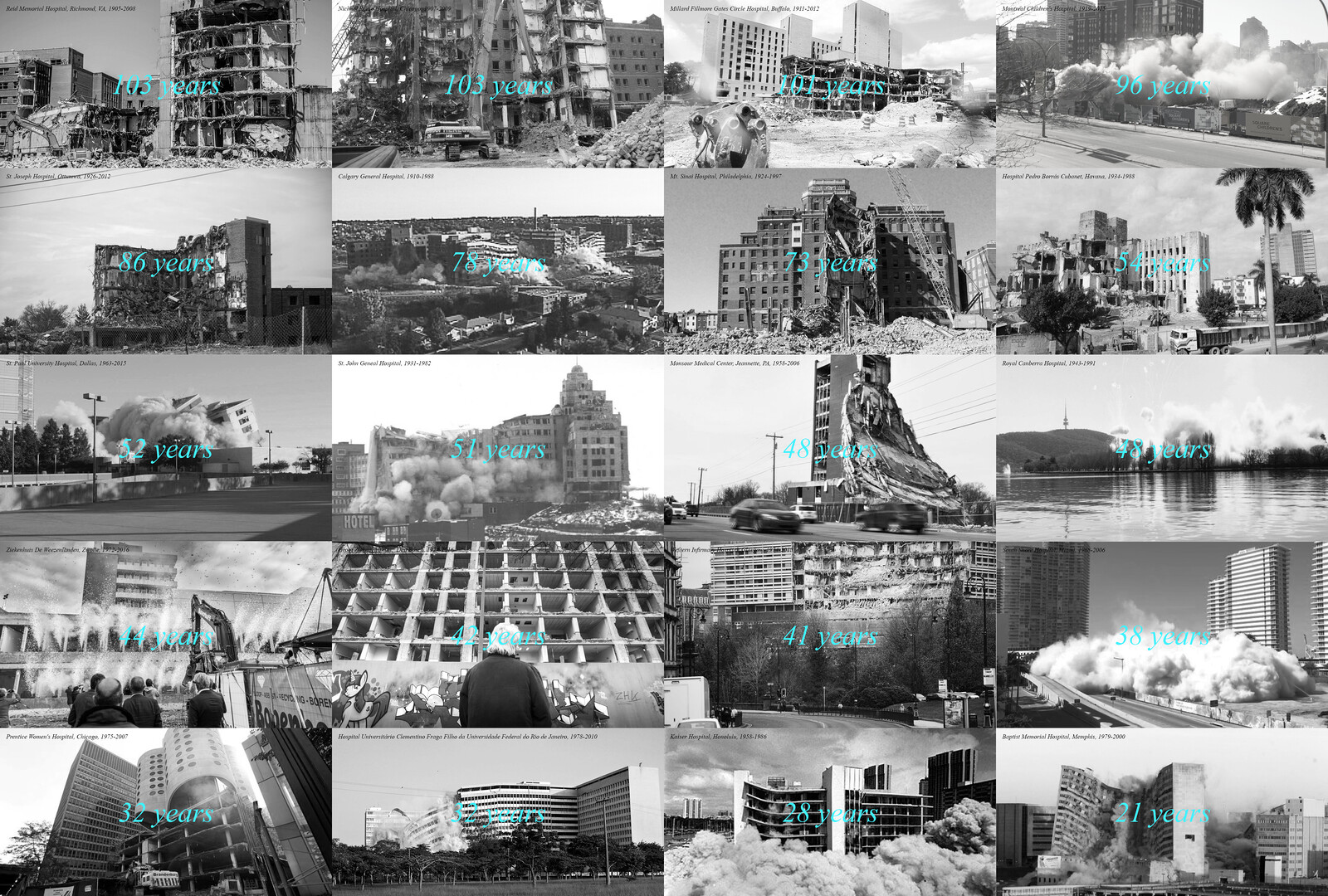

One dramatic transformation that happens to hospitals that doesn’t happen so much to other building types is that hospital sites are constantly rebuilt. Hospital sites become layered, making visible a history of the city. Over time, hospitals lose their formal coherence and they lose their associations with other building types. They accrete additions and renovations made for specific reasons at specific times with no overall guiding principal. These additions maintain variegated associations with building types outside of medicine. Particular parts of a hospital will look like a hotel or a shopping mall while other parts look like a glue factory.

Finally, medical change has a clear impact on hospital care in ways that do not compel architectural change. In many medical situations, we now believe that cure increases in inverse proportion to the length of stay. Procedures that used to entail multiple days or weeks as an inpatient are now handled as day procedures in outpatients. The ethics of care framing twenty-four surveillance in an intensive care suite are distinct from those framing medical work in an ambulatory surgical center, where patients are on-site for less than a day. It makes a lot of difference if you are caring for someone for three hours or three weeks.

Childbirth shows another register of complexity. The idea that childbirth requires a hospital dislodges the care argument—because childbirth is neither cure nor care. In Canada in 1900, almost no woman gave birth in a hospital. In 1950, almost all childbirth took place in the hospital.13 This was not because of a clear increase of safety; few improvements in maternal and infant mortality came with the increase in hospital births. Again, the issue is that the hospital fulfills a social role not captured by the sick role model, and, therefore, not subsumed by the contrast between cure and care.

Overall, the matter-of-factness of medical life—the sense that the patient lives or dies—obscures significant and meaningful complexities. Many chronic diseases admit of care but not cure. Diabetes, for example, warrants an entrenched and lifelong treatment regime called diabetes management. Sociologist Annemarie Mol argues in Logic of Care that the dilemma is not care versus cure—since there is no cure for diabetes.14 In management systems, the site of care moves far from hospital design to the boardrooms of global biotech firms and the interiors of patients’ homes. Diabetes patients ought to take care of themselves through home blood-glucose monitoring and self-tracking of food intake. The ethics of self-care clearly differ from the ethics of the doctor-patient relationship. Is it possible for hospital architecture to frame domestic self-care? Access to hospital care is less important than access to low-cost insulin. What role exists for hospital architecture in a scenario where management regimes promote self-care as normative?

Care is an important intellectual concept that scholars are trying to figure out right now—and not just in medicine. In hospitals, we need to zero in on specific ideas about care; the idea of a shift from care to cure and back again to care is glib. Care ethics can be aspirational rather than analytic, changing the scholarly from description to advocacy. Such rhetoric is less inclusive than it sounds. It sounds helpful to promote care ethics because it sounds unhelpful to promote uncaring.

In order to re-frame the question of care ethics, we might see that the opportunities to ameliorate hospital architecture are not readily cleaved from architectural challenges writ large. We can change our ethics without changing architecture. We can change architecture without changing our ethics. We cannot, however, establish a causal connection between the two. We carry out care practices in a heterogenous range of places. To insist that the elements determined through architectural practices—site planning, ward design, the view through a window—determine care practices risks re-instating the techno-social determinism a new ethics of care was meant to overcome.

Three seminal studies are Charles Rosenberg, Care of Strangers (New York: Basic Books, 1984); Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History, eds. Charles Rosenberg and Janet Golden (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992); and Roy Porter, “The Patient’s View: Doing Medical History from Below,” Theory and Society 14 (1985): 175–198.

Jacob Stegenga, Care and Cure: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Medicine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Susan Reverby, Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

David Theodore and Theodora Vardouli, “Walking Instead of Working: Space Allocation, Automatic Architecture, and the Abstraction of Hospital Labor,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 43, no. 2 (2021): 6–17.

Michel Foucault, Blandine Barret Kriegel, Anne Thalamy, François Beguin, and Bruno Fortier, Les Machines à guérir (aux origins de l’hôpital modern) (Brussels: P. Mardaga, 1979).

The architectural history of the modern hospital is comprehensively recounted in Julie Willis, Philip Goad, and Cameron Logan, Architecture and the Modern Hospital: Nosokomeion to Hygeia (New York: Routledge, 2019).

Lindsay Prior, “The Architecture of the Hospital: A Study of Spatial Organization and Medical Knowledge,” The British Journal of Sociology 39, no. 1 (1988): 86–113.

Jeanne Kisacky, Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870–1940 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017).

Annmarie Adams, Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893–1943 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

Annmarie Adams, “Decoding Modern Hospitals: An Architectural History,” Architectural Design 87, no. 2 (2017): 16–23.

“The Gospel According to Friesen: A Conference at the Hospital Centre,” British Hospital Journal and Social Science Review 76 (1966): 2236–2239.

Quoted in Martin Bressani and Marc Grignon, “The Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève and ‘Healing Architecture,’” in Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light, eds. Corinne Bélier, Barry Bergdoll, and Marc Le Cœur (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 96.

See Wendy Mitchinson, Giving Birth in Canada, 1900–1950 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002).

Annemarie Mol, The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice (New York: Routledge, 2008).

Treatment is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich (2021 and 2025), and Istituto Svizzero, Rome (2025).