These are unprecedented times. The Covid-19 crisis lays bare our interconnectedness. We are all in this together. Or so we are told. On March 27, 2020, while the tribe is in shutdown due to the coronavirus, the Department of the Interior issues a directive to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to strip Mashpee Wampanoag of its homeland and sovereignty.1 Simultaneously, the destruction of sacred sites of the Tohono O’Odham along the colonial borderlands had begun, and the Apache and Yavapai sacred sites suffer destruction at Oak Flat.2 By June 2020, Navajo Nation has the highest infection rate in the United States—greater than that of Wuhan at the height of the outbreak in China.3

On April 7, 2020 we, the coauthors, are having a long conversation via text message. Andrea writes:

I can’t stop thinking about the smallpox and flu of 1918 and how those illnesses affected Native Nations who are so social, so interdependent and reciprocal. I also realize that I self-isolate a lot when I make paintings, but nothing is more isolating than fasting (vision quests) and that is said to be medicine. Have you seen the film Ikwe? It is pretty strange, but was initially supposed to be entirely filmed in Ojibwe. Its smallpox, sole survivor ending is so sad… I think of Boise Cascade paper mill giving me (and all the children in my community) asthma while deforesting the woods around us. We carry that ailment in our bodies and now are at a higher risk to this thing. One injustice becomes a lifetime of injustice, compounded over so may intersecting capitalist wrongs.

There lies a historic precedence for the unleashing of epidemics by settler colonialism that are carried within certain bodies, both human and more-than-human, and are ongoing. These bodies carry within them the material processes of violent extraction that are the ground of settler collective life.

Now imagine that it is 1988, the Rainbow Warrior Festival is being held at the Paolo Soleri Amphitheater in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Floyd “Red Crow” Westerman sings a cover of Kris Kristofferson’s They Killed Him, altering the lyrics of a song that laments the deaths of Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, Jesus Christ, John F. Kennedy, and Robert F. Kennedy. Westerman adds a verse honoring Sitting Bull, replacing the verse about the Kennedys—men who were not holy by any conventional sense of the term. His added lines read:

There is a place called South Dakota / It’s a home of Sitting Bull / He was branded a redskin savage / When he tried to defend his land that day / But his dream of beauty, they could not burn away / Just another holy man who dared to be a friend / MY GOD, THEY KILLED HIM!

Westerman’s version of the song would continue to be referred to in Indian Country as Just Another Holy Man.

The year is now 2002. Across a dimly lit set, Hidalgo (2004) is being filmed. Backstage at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, Floyd Westerman walks through cowboys. His feather bonnet catches the spotlight as he exchanges sympathetic glances with Viggo Mortenson in the mythologized role of Frank Hopkins. Westerman is Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota, an actor, an activist, and a singer, but in this role Westerman portrays Chief Eagle Horn, a man who, having witnessed genocide, bravely walks into the spotlight of a circus ring. The crowd jeers and throws stones at him, or rather, at Chief Eagle Horn. Although the film fits squarely into the Western fantasy genre, there is one scene it gets right: Native warriors who fought military incursion into their land survived by reenacting those battles to audiences of violent settlers in as little as a few months after battles were fought. They played the role of the heel, and were living trophies caught up in a rapidly changing economy brought on by their reduced land base on static reservation. Native people who were pushed into starvation were subsequently forced to survive through their further exploitation and the exploitation of settler desire to gloat their fresh conquests.

It is hard to imagine Sitting Bull riding out into an auditorium or a big tent theater reenacting battles he fought in, but it happened. Films and wild west pageants erase, alienate, and transcribe these memories into false memories of both the disaffected audience and those who lived first-hand through massacres and battles. The framework is baked into the words that are used to organize collective memory and the forms of possession that are used to organize collective life. “Pre-contact” and “pre-Columbian” feign neutrality where “pre-invasion” more accurately describes the activities of “explorers” and “pillagers.” One person’s “battle” is another person’s “massacre.” One person’s “public land” is another’s “stolen land.”

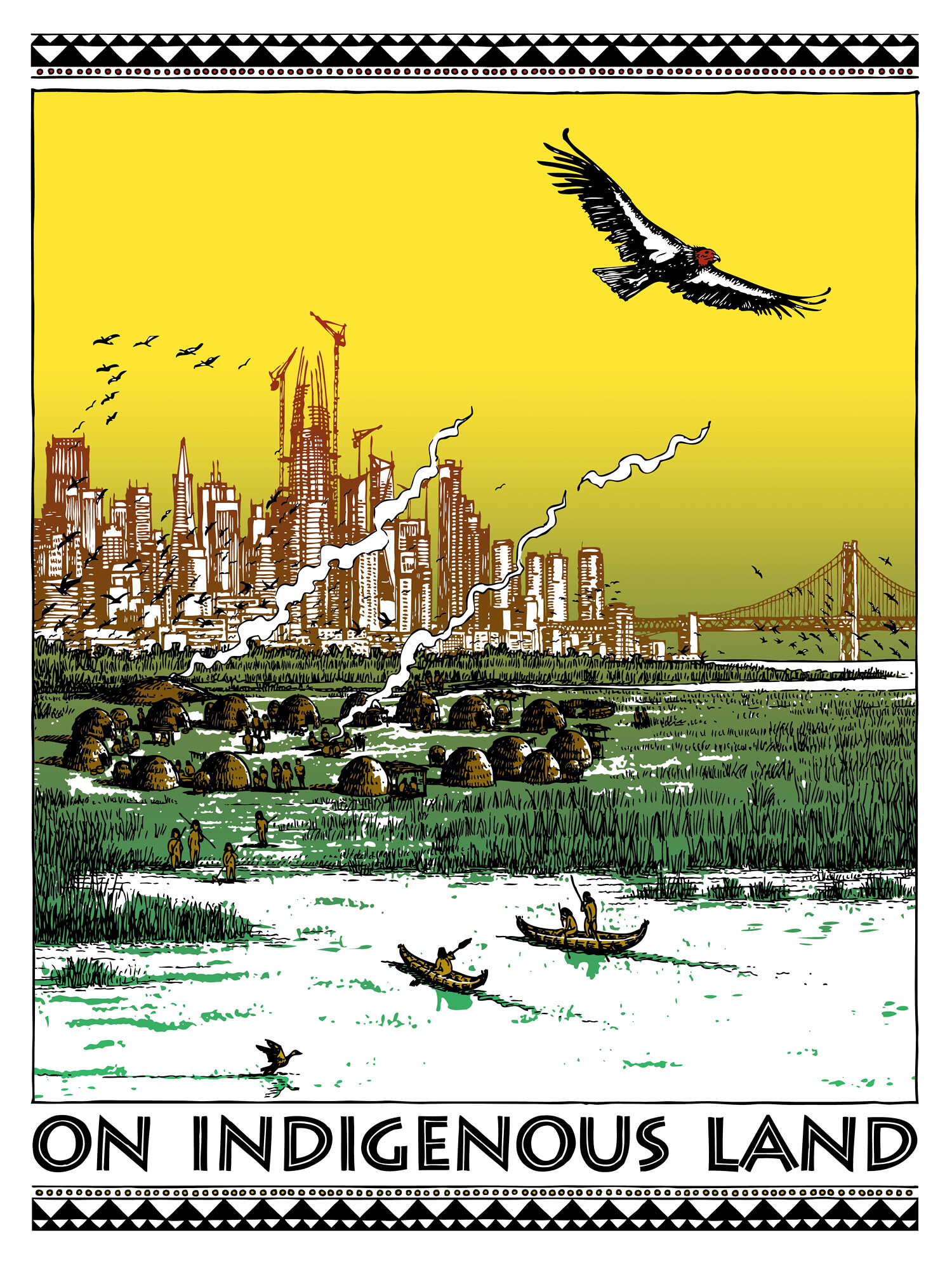

The settler forever present tense sees the land as a blank canvas, a neutral setting where the theft of land was done long ago by people long dead. The false neutrality of the settler “public” life is a willful forgetting—a denial of land theft and the mass killing of Native people, but also its monument.

It is 2017, Andrea is sitting on a porch with Gwen Westerman, the niece of the late Floyd Westerman. They are talking about genocide and massacres. Westerman talks about the thousand-yard stare that was observed in the expressionless faces of veterans returning from World War II, on the faces of Depression-era photographs by Dorothea Lange, and that she had noticed the same look on the faces of Native children in photographs taken at Native American boarding schools too. Her uncle Floyd had experienced boarding schools. She mentions that when her uncle played the role of Chief Eagle Horn in Hidalgo, he was deeply affected by the jeers of the audience of extras. He imagined himself as Sitting Bull who had fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn only to be mocked and ridiculed by audiences of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows.

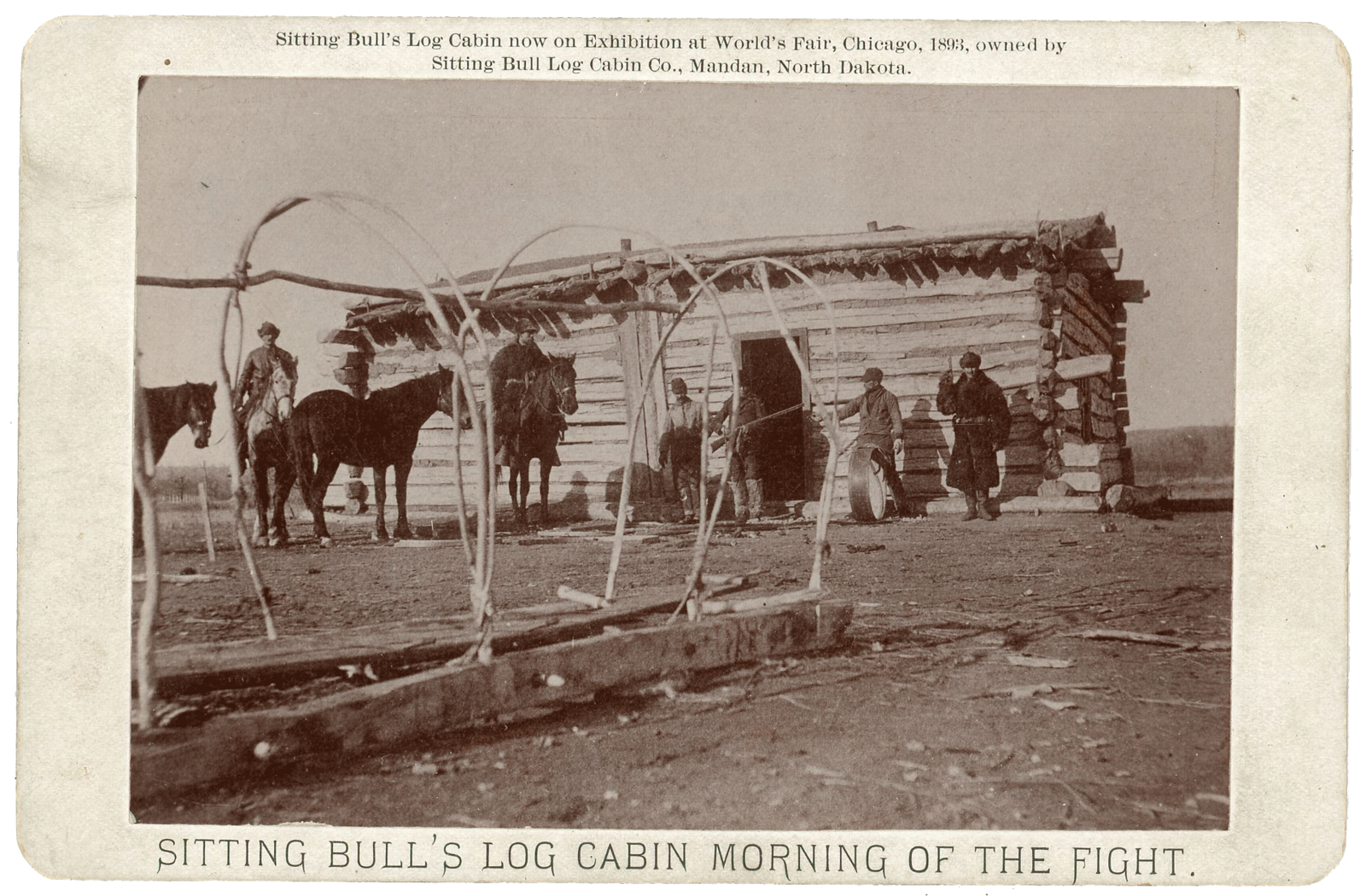

Now reach back to a time in your mind to a time that was before you were born, back to December 15, 1890. At 5:30 am, nearly forty men surround a little cabin in Grand River, South Dakota on the Standing Rock Reservation. The cabin’s door faces east, catching the dawn’s light and shadows of soon-to-be assassins. The forty men wait under orders to arrest Sitting Bull who is waking up next to his wife, readying himself, and singing her a song. Sitting Bull takes his time to arrive at his door. This arrest is a misunderstanding, but perhaps an intentional misunderstanding. Several photos are taken outside of the log cabin. These photos will eventually become souvenirs or postcards, and the photographer anticipates future profits. The forty men, Native themselves, become impatient as a crowd of Sitting Bull’s friends gather and chant, “You will not take our chief!” Sitting Bull emerges at the door, followed by confrontation as his friends intervene. Shots are fired. A horse tethered nearby hears the gunfire and dances. A witness, in a moment of sheer terror, must have noticed the horse dancing and held onto that memory. The horse is Sitting Bull’s horse, and it had been trained to pantomime as though it was receiving bullets when it heard gunfire in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows.4 The dust clears. Sitting Bull lays dying with a shot to the chest and a shot to the head.

It is the evening of December 28, 1890. Thirteen days after Sitting Bull’s death, 500 members of the US 7th Cavalry place four rapid-fire Hotchkiss-designed M1875 mountain guns around 400 disarmed and bereaved Lakota Ghost Dancers. At daybreak the next morning the Lakota people are fired upon, leaving over 300 of their people dead. The families of the deceased are left with a mass grave to cry upon.

The Columbian World’s Fair opens on May 1, 1893, four-hundred years and seven months after Columbus made landfall on an island decidedly not India. May 1, 1893 is a mere two years and six months after Sitting Bull was murdered while standing at his cabin’s door. That same cabin’s door along with the rest of the building was purchased by some enterprising-yet-perverse individuals who reassembled the building in Chicago on the Midway Plaisance. Visitors first encounter the cabin while entering the World’s Fair in an area reserved for living exhibits of “ethnographic villages” and other sensationalized displays of overtly racialized cultures, on their way to the Women’s Pavilion and beyond that to the White City. The Plaisance is designed as a grand Baroque-style corridor, linking two parks and anchoring a suburban development intended as a nature-inspired paradise for affluent Chicagoans looking for an escape from the city filth. Permeating the Plaisance is the sublime whiff of Anglo-Saxon superiority. The place where Sitting Bull’s cabin stands would later be an unremarkable spot of grass on the south side of the boulevard, at the intersection of 59th Street and Drexel Avenue, across the street from what is now the University of Chicago’s Center for Research Informatics.

In 1893, Sitting Bull’s log cabin is concealed behind the walls of the exhibition façade filled with romantic imagery that one may expect to see on the cover of a western written by Karl May. The enclosure conceals what a ten-cent admission would give access to, and it appeals to settler emotions around an active genocide. It is a safe place to mount a trophy of war. But the designers of the exhibit failed to anticipate a major outcome of the exhibit: Sitting Bull’s log cabin becomes a memorial for many Native people attending the fair. It becomes a place where Native people who are mourning come to pay their respects to the man who had become synonymous with Native power and survival. They arrive in numbers, and we can imagine that they stand in the door frame and say goodbye. Sitting Bull’s wife is also regularly at the exhibit, selling wares to support herself. She has sold the dancing horse back to Buffalo Bill and likely the log cabin. It is hard to imagine what she is feeling, if she is witnessing settler racism within those walls, if she is being cared for by Native people who memorialize her late husband there. The cabin is a symbol of victory and dominance to some, but a memorial and place of reverence for others. After the fair, it will be reported that the log cabin will be assembled in Coney Island and then again in Antwerp, Belgium, but what became of it after that is unknown.5

On July 4, 1836, dignitaries, canal commissioners, and ladies in fancy dress are gathered two miles west of Lake Michigan to witness the groundbreaking of the Illinois and Michigan (I&M) Canal amid a frenzy of real estate speculation. With much fanfare and ceremony, the Declaration of Independence is read, speeches are made, and canal commissioner William Archer turns the first shovel. The canal would transform a vast Native wetland into Chicago: parcels of dry settler-owned real estate traversed by a navigable waterway. It would connect the Mississippi to the Great Lakes, inaugurating a global trade route under the control of the Americans. The ceremony rehearses a much-publicized grand vision: “If we glance an eye over the immense regions thus connected; if we regard the fertility of soil, the multiplicity of product which characterize these regions; and if we combine these advantages afforded by nature with the moral energy of the free and active people which are spreading their increasing millions over its surface, what a vista through the darkness of future time opens! The view is indeed almost too much for the faculties of man.”6

The United States had recently granted the state of Illinois 290,000 acres of public land on either side of the canal route, with alternate tracks to be sold at auction in order to finance the cost of construction. This system would become a facet of almost all subsequent land grants, including grants for railroad construction to accelerate settlement and westward expansion. The Canal Commission is set up to mediate the conversion of public lands to privately held real estate. The fancy folks attending the ceremony stand to make a killing over subsequent cycles of real estate bubbles, and in the creation of credit instruments, Canal scrip and bonds, which themselves can be bought, sold, and speculated upon. The mood is only slightly dampened when, upon departure, the delegation is attacked by Irish laborers uninvited to the ceremony. Neither wealthy capitalists nor the poor immigrants who would be paid for their labor in rapidly devaluing Canal Commission scrip give much thought to how the land underwriting this speculative economy became “public land” to begin with.

Despite being called a groundbreaking ceremony, the day’s festivities are not motivated by imminent construction. William Archer and his fellow attendees likely know it will be over a year before any other shovel of dirt is turned after the ceremonial one (even while they may not anticipate the cycles of boom and bust that will leave them wealthy and the state bankrupt). The heady enthusiasm of the day is prompted instead by the infusion of capital from European financiers who, until recently, had been skittish about investing in large-scale capital projects on the frontier, due to the risks to returns on investment posed by Indigenous peoples and legal orders. The passing of the Indian Removal Act helps boost investor confidence. Less than four years ago, US federal troops, along with Illinois and Wisconsin militiamen, enforced removal by orchestrating the slaughter of Black Hawk’s people—warriors, elders, women, and children. Many of the same militiamen who carried out these massacres, including William Archer, are now in attendance at the I&M Canal groundbreaking festivities. With the business of Indian killing reaching fever pitch, the state of Illinois pledges its credit for the repayment of Canal Commission bonds, and investor liquidity begins pouring into the coffers, unleashing large-scale colonial settlement in the canal zone.

The I&M Canal groundbreaking party is giddy with fresh liquidity and fresh slaughter.

It is August 24, 1816. The United States coerces representatives of the Council of Three Fires into signing the Treaty of St. Louis, a cession that includes a 100-mile long, twenty-mile wide strip of land along the Illinois river to the mouth of the Chicago river—the region targeted for a future canal. Treaty-making, and the exclusionary violence that underpins it, is a very peculiar kind of theft; not merely a theft of property, but a theft that creates property.7 This theft creates a form of settler property called “public lands” while recursively bestowing upon Native nations a newly invented and inferior or subordinate order of property that can be operationalized only through alienation. Native nations, in other words, are turned into property owners, with the right only to sell. This theft is property-making, and it lies at the heart of the legal conceit of US sovereignty in North America.

In its wake, the juridical construction of the regime of public lands makes possible the emergence of property in severalty in all its various forms—real property, personal property, mineral rights, rights of way, as well as the speculative financial instruments and forms of capital accumulation (such as the corporation and its shares) born alongside them.

Across the eastern woodlands, the central prairies, and later the grasslands of the west, Native place becomes dismembered and subject to relentless extraction into various forms of settler “common” and “public” property—public lands, outer commons, common pastures, forests and rivers, the open prairie. Bison, fish, and other animals become settler common property, while settler-owned hogs and cattle remain private property wherever they roam.

The treaty of St. Louis stipulates “That the said tribes shall be permitted to hunt and fish within the limits of the land hereby relinquished and ceded, so long as it may continue to be the property of the United States,” suggesting that land held in the public domain by the United States will be open to all. But wherever Native people are legally allowed to exist and retain rights, “in practice the margin of subsistence would be made to shrink to the vanishing point for Indians living on the colonial commons.”8 Over the next one hundred and eighty years, the politics of defending the settler commons—as places and as doctrines of access rights—will routinely forget and disavow its relentlessly expansionist nature in the North American context. But in 1816, “public land” explicitly names procedures of invasion, occupation and settlement.9

On July 2, 1836 the I&M Canal Commission sets aside a thin strip of muddy land along the Lake Michigan shore which it has been unable to sell at auction, famously designating it as “a public ground—a common to remain forever open, clear, and free of any buildings, or other obstruction whatever.”10 The urban “common” at this time is likely understood as a place where matters important to urban governance unfold: parade grounds for local militias; markets; political speeches and official ceremonies; auctions; and other such activities. One hundred eighty-four years later, half a mile of settler fill will have expanded this strip into the lake. One hundred eighty-four years later, this fill will have become a massive, multi-level structure. On the rooftop of this structure will sit Grant Park, the crown jewel of Chicago’s public park system envisioned by Daniel Burnham, architect, power broker, and organizer of the World Columbian Exhibition of 1893. Stolen land to public land to common ground to public park.

Settler Chicagoans will speak of Lakefront Park, later renamed Grant Park, as born a commons. The only history that will be told is the story of the fight to protect it as common ground against incursion by competing industrial and rail interests, and government projects in a fight largely led and bankrolled by Montgomery Ward and the Commercial Club of Chicago. But this public ground is built materially, juridically, politically, and rhetorically in the process of ongoing Native dispossession and erasure are operationalized while shifting configurations of settler publicness. Implicit in the vision for the park system envisioned in the Plan of Chicago—comprised of an urban park district and suburban nature preserves—is role of a settler city in managing the threat of civil unrest and political instability. Much like the I&M Canal, the public park would become the vehicle for a politically-unifying vision sponsored by the city’s elites, a civilizing project for transforming territory and its residents.

On July 4, 2020, the coauthors of this essay are having a series of conversations about writing this text. Rozalinda takes notes:

You write about “we” from an Anishinaabe perspective, about the two forms of “we” in Anishinaabemowin: inclusive and exclusive. And “we” can mean, for example, being collectively implicated as part of a river.11 From this vantage point, you throw into stark relief both the anthropocentrism and the presumed inclusiveness of “we” in English. This inclusiveness of the collective “we”— “we the people,” “we the public,” etc.—is a lie, masking the exclusionary violence that is a condition of its possibility. You also call it coercive, and that came as a surprise … this “we” embedded in language is also embedded in forms of property and possession. What’s underneath this false and violent “we” organizes relations of possession and domination (over land, over specific bodies, human, less-than-human, non-human).

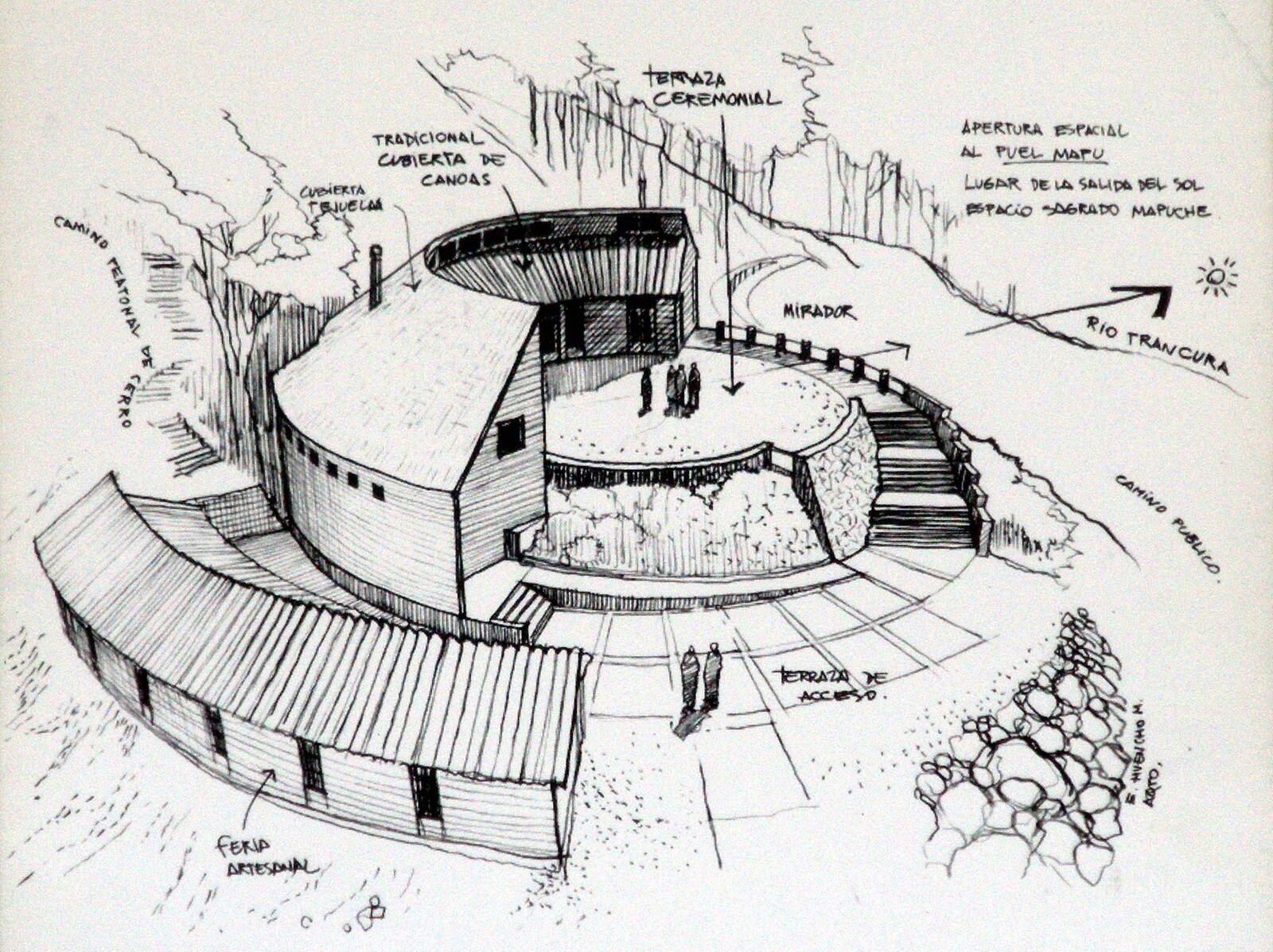

On Friday, September 24, 1920, Chicago holds its first Indian Day kickoff event in a Cook County Forest Preserve in Deer Grove. From opening day, highways are backed up for miles. Over 150,000 people attend on Sunday alone, clamoring for a look at Indians performing dances, sports, and ceremony. And for those who cannot attend in person, “the filmed story of the enchanting scene was sent broadcast throughout the United States, Canada and distant lands.”12 So formidable is the public assembled to gawk at Natives that next year Ransom Kennicott, chief forester of the Forest Preserve District, would propose a permanent Indian Village populated by what would be called “forest preserve Indians.” The preserve would plant willow, the Indians would make baskets to sell to the tourists, and the Indian Fellowship League will select the only the “right class of Indians” for the village.13

The Indian Fellowship League (IFL) and The Society of American Indians are two organizations that emerge in the first two decades of the twentieth century in Chicago. Native members of the IFL in Chicago seek to challenge dominant stereotypes, mobilizing for citizenship for Native Americans, as well as initiating cooperation among tribes and urban communities around redress for fraudulent or broken treaties. At the Indian Day celebration, these hopes are “overshadowed by the opportunity for tourists to gawk at” Indians as “vestiges of a dying race.”14

Between 1870 and 1964, the formation of the first National Park, the formation of the National Park Service and the passage of the Wilderness Act, various scientific, aesthetic, and regulatory practices emerge to violently empty Indigenous lands of Indigenous peoples in order to create a wilderness to be preserved. Cook County Forest Preserve (CCFP), the oldest and largest nature preserve district in the US, is envisioned in Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago as an integral part of the metropolitan park system. It would inaugurate a new racialized and exclusionary settler commons: the urban wilderness.

The Park District and CCFP reconfigure settler colonial domination in response to ongoing Indigenous practices of return, restoration, and renewal of relation with the lands currently occupied by Cook County and Chicago. CCFP and the Chicago Historical Society gain decisive influence over the IFL, detouring the political goals of the Native activists in order to raise money for the Historical Society’s American History collection, and to “advance the cause of conservation using Indians as props in American Indian Day celebrations.”15 Over the next decades, CCFP would also be the instrument through which direct seizures of lands held in fee simple by Potawatomi families is accomplished, most notably the so-called Caldwell and Robinson Reserves.

© Ted Sitting Crow Garner, 2020.

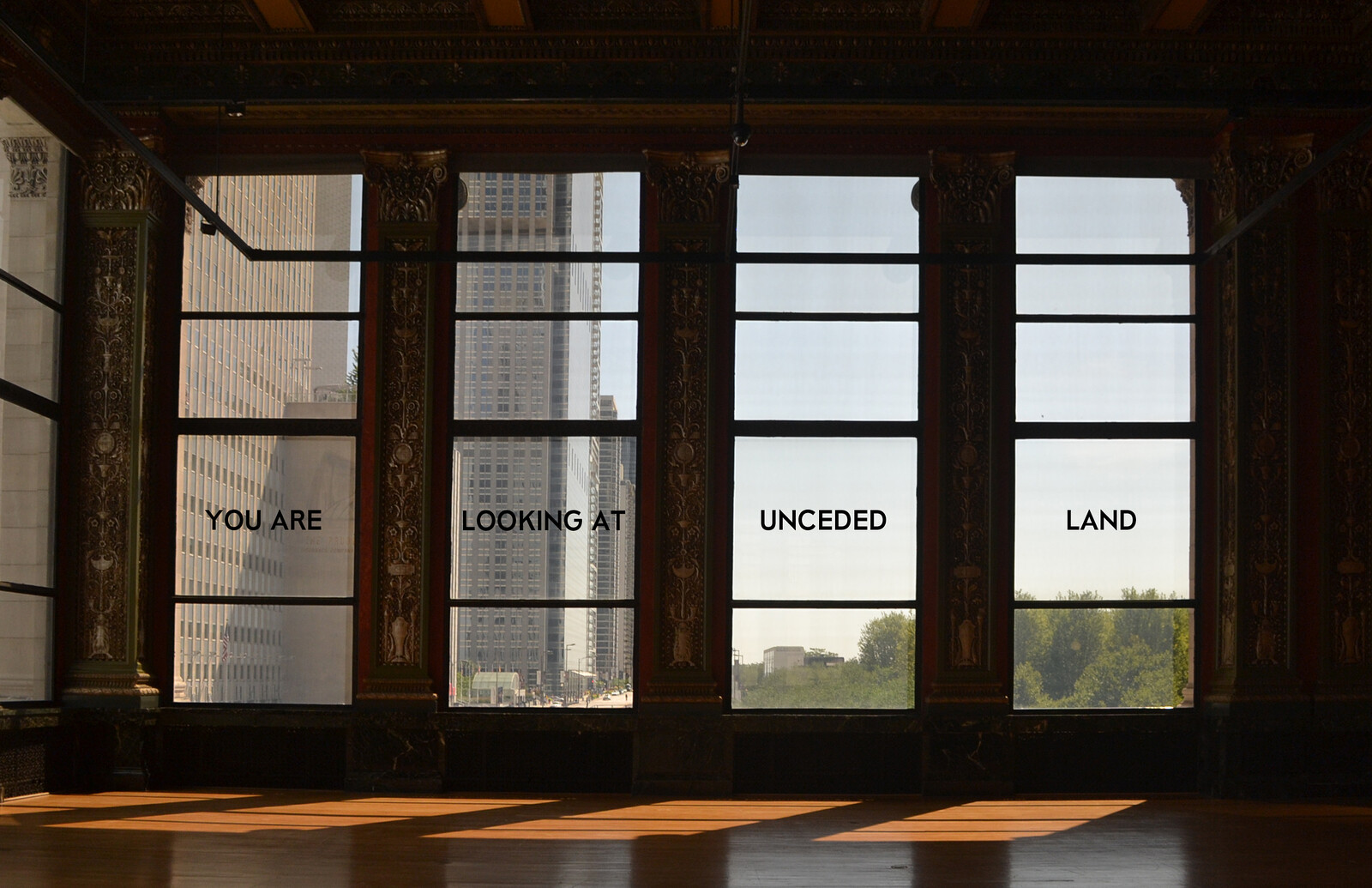

It is early morning July 24, 2020 in Grant Park, Chicago, Illinois. So early that it isn’t quite closing time, but the bars are sensibly closed. Blinding beams of light encircle a crew of Chicago city workers who are assembled on a crane and around the base of the Columbus monument. A crowd emerges and cheers. There is laughter and joy. Some are frozen in the moment, as the figure becomes detached from its pedestal. The mayor’s office has ordered the temporary removal of the Columbus statue, in response to escalating protests. In the remarkable document “Lessons from Grant Park,” organizers articulate a precise understanding of the moment and of the geographic grounding: “Grant Park is unceded land… Grant Park is a celebration of colonialism.”16

As the crowd watches the removal of the statue, the city workers are performers; they are in the spotlight in an exedra which serves as a functional stage. One man among them is not merely performing his assigned role for the city—he instead performs his own counter-memorial in gesture, image, and text. We present it below, in its entirety, as it was offered to us. The man that helped physically remove Columbus’s image from its pedestal is Standing Rock Sioux, from the land in South Dakota that is the land of Sitting Bull.

I am the person that took down that Columbus sculpture.

I am a long resident artist here in Chicago, who has made and installed sculptures here for nearly fifty years, both of my own design and the works of others.

I am also of American Indian and Caucasian ancestry on both sides of my family, which brings up its own historical resonance in these times.

I was asked to consider participating in the removal on very short notice, having installed and removed numerous artworks for the Park District and other municipal and cultural entities here in the City, regionally and nationally.

Once it was determined that we could obtain the required equipment on such a short schedule, the team proceeded. We were delayed by the need for the police to remove, first the “protesters,” then “counter-protesters” including apparently a large contingent from the Fraternal Order of Police. Feelings were running high. Indeed, while working, we were subject to repeated taunts and jeers from on-duty members of the police.

My motivations were for public safety, having seen the previous removal attempt on media. Also, I have had my own artwork destroyed, most notably by the Field Museum, who destroyed a large outdoor commission during their “Museum Campus” renovation.

Destroying artwork is wrong, whatever the reason; but most particularly because you don’t agree with it. That way is the way of Nazi Germany, who destroyed many works by artists who have since become pillars of the modernist tradition; while stealing works that had passed conventional muster and had considerable monetary value at the time. It must be remembered that beside their other crimes, the Nazis were the exemplars of the Imperialist ethos: I WANT IT!—IT’S MINE!

Not having a stereotypically “Indian” complexion, I have been, in my time, physically attacked and beaten, both for being Indian, and for being “White.” Despite the 1619 movement, the true original sin of the history of the Americas was and continues to be the treatment of its aboriginal peoples. Three of my forebears, two of them my namesakes, signed treaties with the United States to try and protect the rights of their people, yet those rights are still under attack, and Indian people, particularly women, continue to “disappear” nationally at an alarming rate.

The eventual disposition and locations of those (and other) sculptures is best dealt with in more cool-headed times. An event from the actual removal may be instructive. Some of the historic physical anchors holding the piece let go suddenly and without warning, letting the piece fly free before we had achieved optimal lifting conditions. Luckily, good lifting practice and preparation in advance prevented that from being catastrophic. Perhaps that is a metaphor for the situation writ large.

—Ted Sitting Crow Garner, enrolled member Standing Rock Sioux Indian Tribe. © Ted Sitting Crow Garner, 2020.

The Secretary of the Interior, “Memorandum: Littlefield v. Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribe, 951 F.3d30 (1st Cir. 2020),” March 27, 2020, ➝. This was subsequently challenged; see Acee Agoyo, “‘You’re Gonna Have a Lot of Trouble’: Judge Trashes Trump over Changes in Tribal Homelands Policy,” Indianz, May 20, 2020, ➝.

See: Teo Armus, “‘You Don’t Control the Border’: Indigenous Groups Protesting Wall Construction Clash with Federal Agents,” The Washington Post, September 23, 2020, ➝; Debra Utacia Krol, “Tribal and Local Activists Air Concerns about Resolution Copper Mine at Oak Flat for Congressional Subcommittee,” The Arizona Republic, March 13, 2020, ➝.

Sahir Doshi, Allison Jordon, Kate Kelly, and Danyelle Solomon, “The COVID-19 Response in Indian Country,” Center for American Progress, June 18, 2020, ➝.

Deanne Stillman, “Sitting Bull’s Dancing Horse,” True West Magazine, January 10, 2018, ➝.

Mark Holman, “Where Is Sitting Bull’s Cabin?” Sitting Bull College Library, January 7, 2019, ➝.

R. Brookes and William Darby, Darby’s Universal Gazetteer, or, A New Geographical Dictionary…Illustrated by a…Map of the United States. The 2nd Ed., with Ample Additions and Improvements (Philadelphia: Bennett & Walton, 1827).

This analysis of dispossession is developed in: Robert Nichols, Theft Is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

Allan Greer, “Commons and Enclosure in the Colonization of North America,” The American Historical Review 117, no. 2 (April 2012): 365–86.

Refers to arguments made in Andrea Carlson, “The Mississippi River Is the Opposite of the Anthropocene,” Anthropocene Curriculum, February 10, 2020, ➝. Specifically, the quote, “the Mississippi River is an inappropriate mascot for the Anthropocene because this association forecloses on Native philosophies about water and place that implicate us as part of the river.”

Illinois and Michigan Canal commissioners, “Map of Chicago and Additions, 1836,” July 2, 1836, in Encyclopedia of Chicago, 2005, ➝.

Referring to Carlson, “The Mississippi is the Opposite of the Anthropocene.”

Rosalyn R. Lapier and David R.M. Beck, City Indian: Native American Activism in Chicago, 1893–1934 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 87.

Collin Fisher, “Multicultural Wilderness: Immigrants, African Americans, and Industrial Workers in the Forest Preserves and Dunes of Jazz-Age Chicago,” Environmental Humanities 12, no. 1 (2020): 51–87.

Lapier and Beck, City Indian, 103.

Ibid., 84.

Chi Nations and Black Lives Matter Chicago, “Lessons from Grant Park,” Black Lives Matter Chicago, August 2020, ➝.

The Settler Colonial Present is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Settler Colonial City Project, with the support of the Department of the History of Art and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.