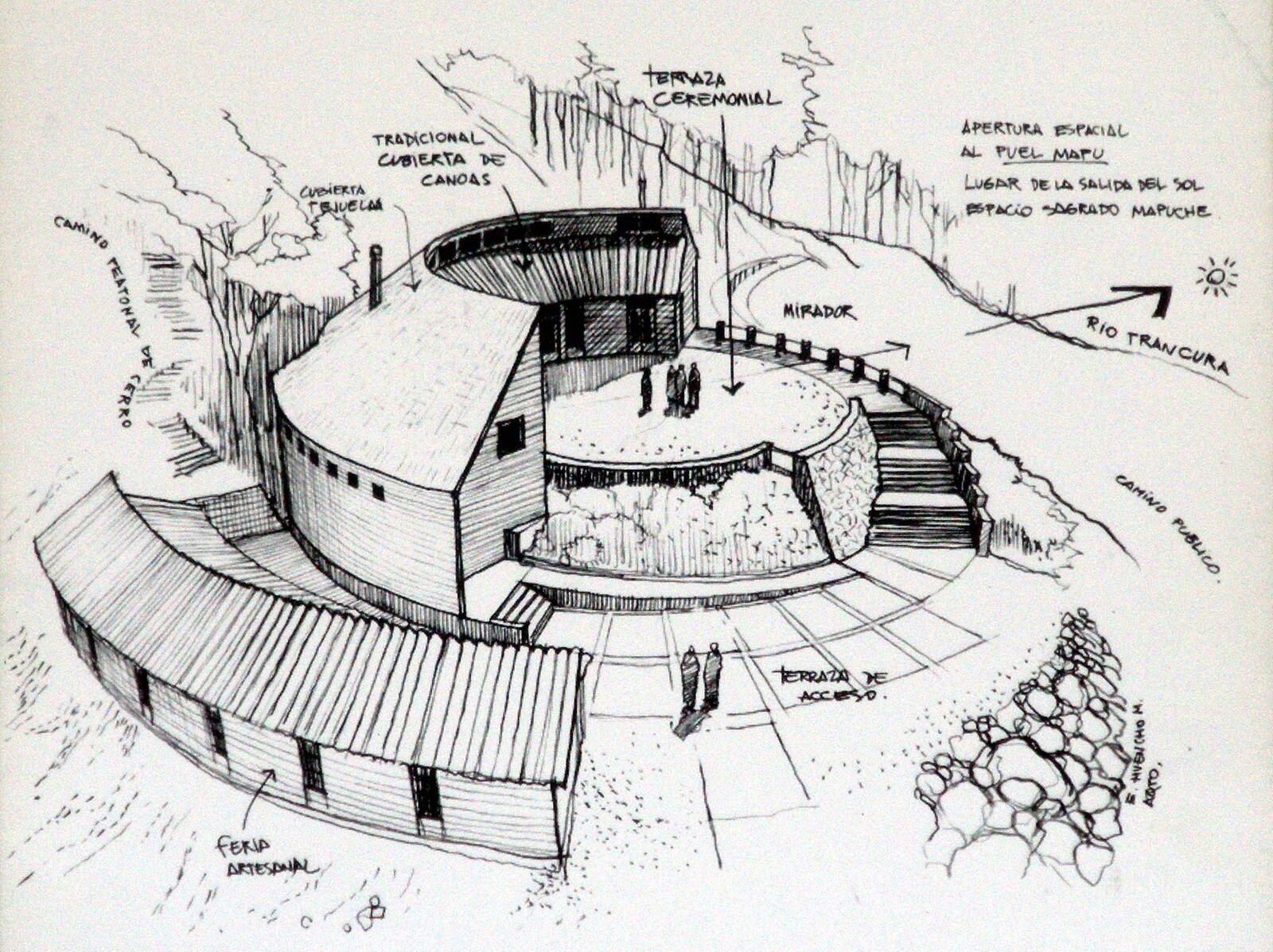

The Settler Colonial Present is a collaboration between the Settler Colonial City Project and e-flux Architecture, featuring contributions by Anita Bakshi, Andrea Carlson (Ojibwe) and Rozalinda Borcilă, Eliseo Huencho (Mapuche), Paulo Tavares, and K. Wayne Yang, as well as statements by Jonathan Cordero (Ramaytush Ohlone), John N. Low (Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians), Shalini Agrawal and Shylah Hamilton, Kanyon Sayers-Roods (Costanoan Ohlone and Chumash), Mark Jarzombek, and the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust. Exploring architecture’s constitutive relationship to settler colonialism in the Americas, contributions reflect on spatial violence in Anishinaabe, Karajá, Kumeyaay, Ramapough, Mapuche, Aymara, and Ohlone territories, as well as the ways in which the peoples of these lands have resisted and contested this violence.

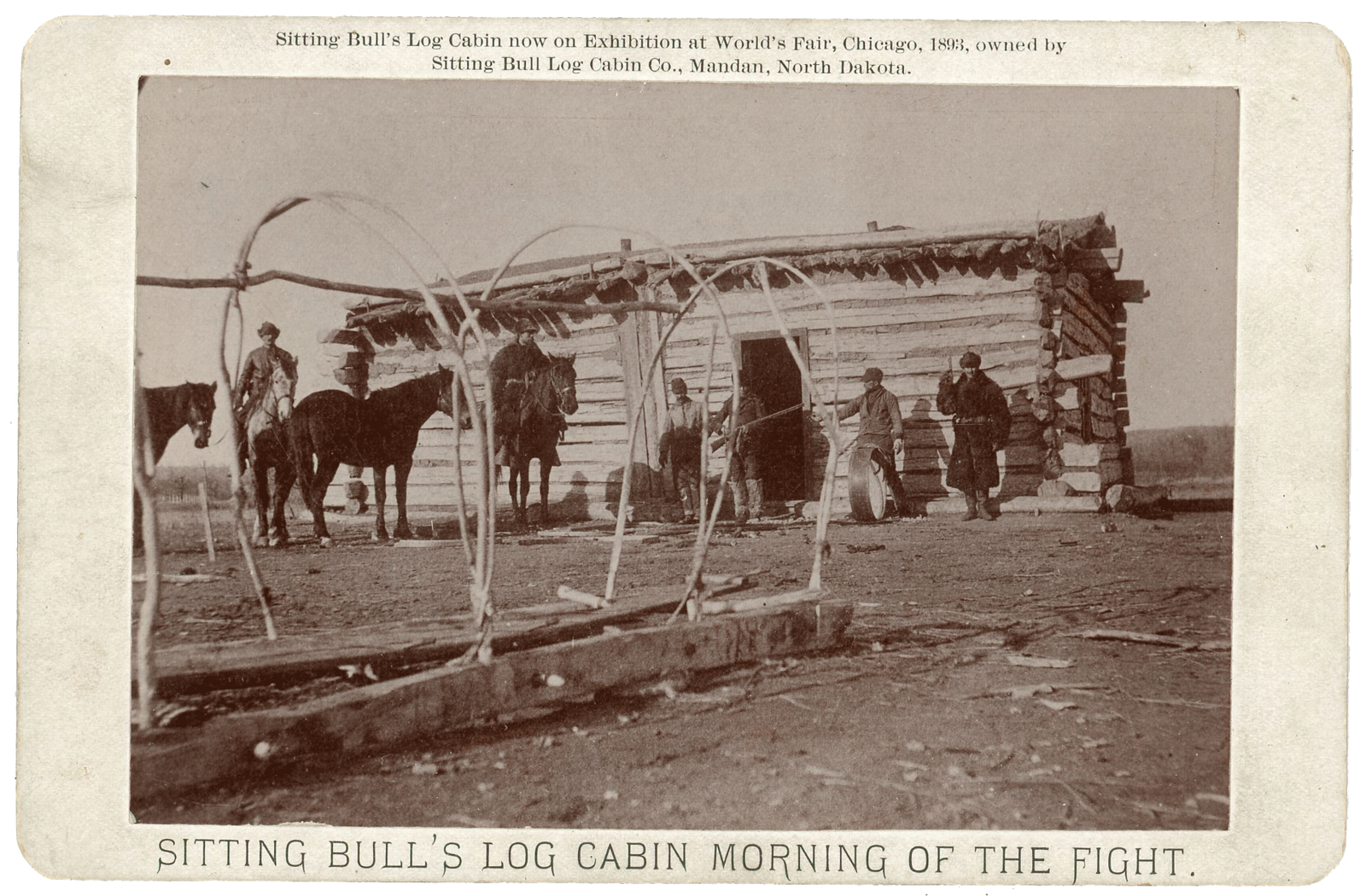

Memories of October 12 in the Americas are conflicted and painful. The date is remembered as the moment of European arrival to the Americas, marking the start of colonial and settler colonial processes in the continent, as well as the Indigenous resistance and struggle against these processes that continues to the present. Throughout Spain and Latin America, the date was problematically designated as “Día de la Raza” (Day of Race, est. 1914) to celebrate a peaceful and harmonious union between Spain and its former colonies. Only more recently has this designation been challenged and criticized. In the United States, October 12 was first celebrated as Columbus Day, and, more recently, counter-celebrated as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. The paradox of celebrating the arrival of a Genoan explorer to Guanahani (now part of the Bahamas) throughout a continent that is often conflated with the United States is only one of the ways in which settler colonialism has obfuscated and elided its actions and, to follow Walter Benjamin’s dictum, mobilized the tropes of civilization to legitimize its barbarism.

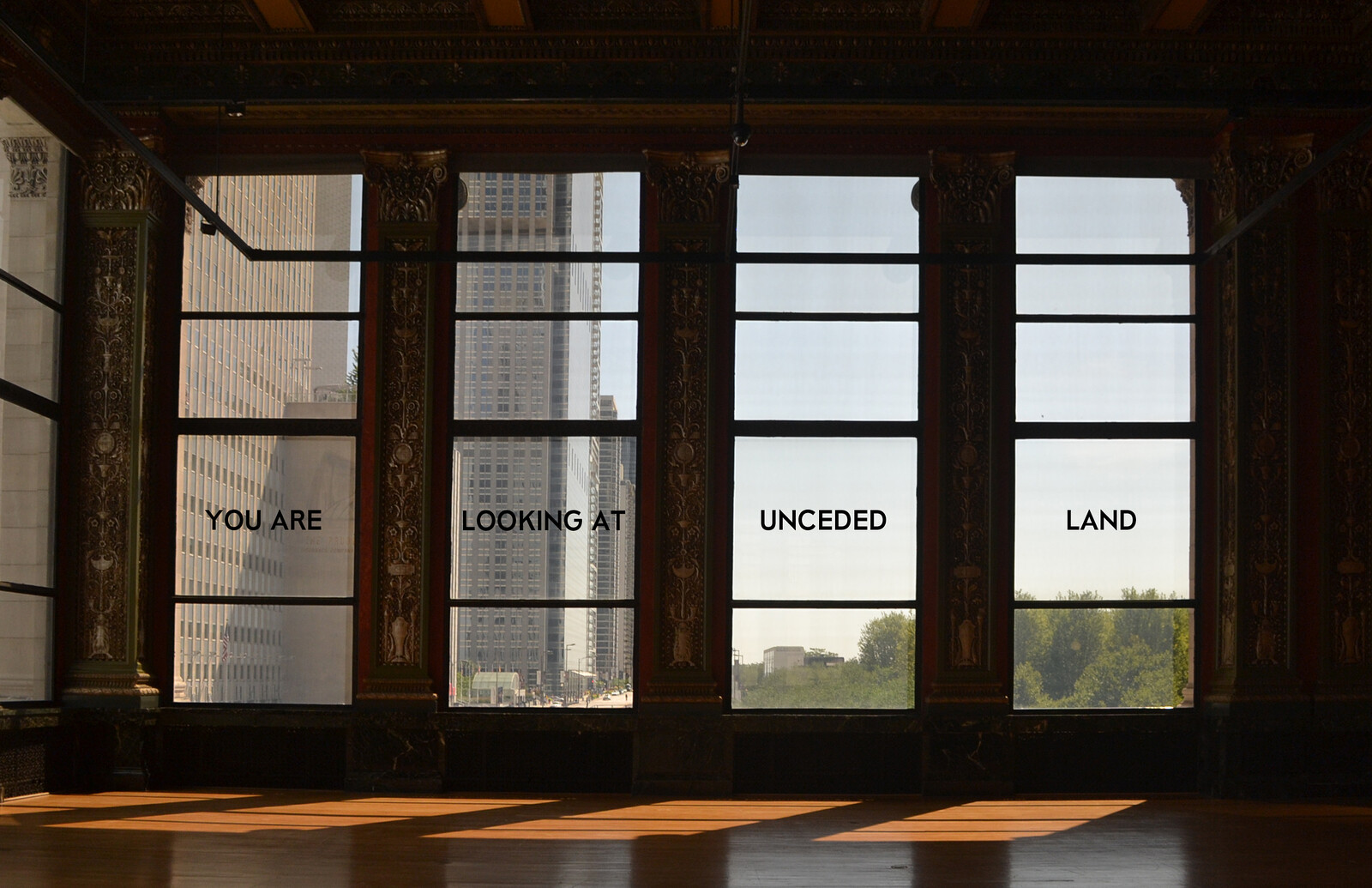

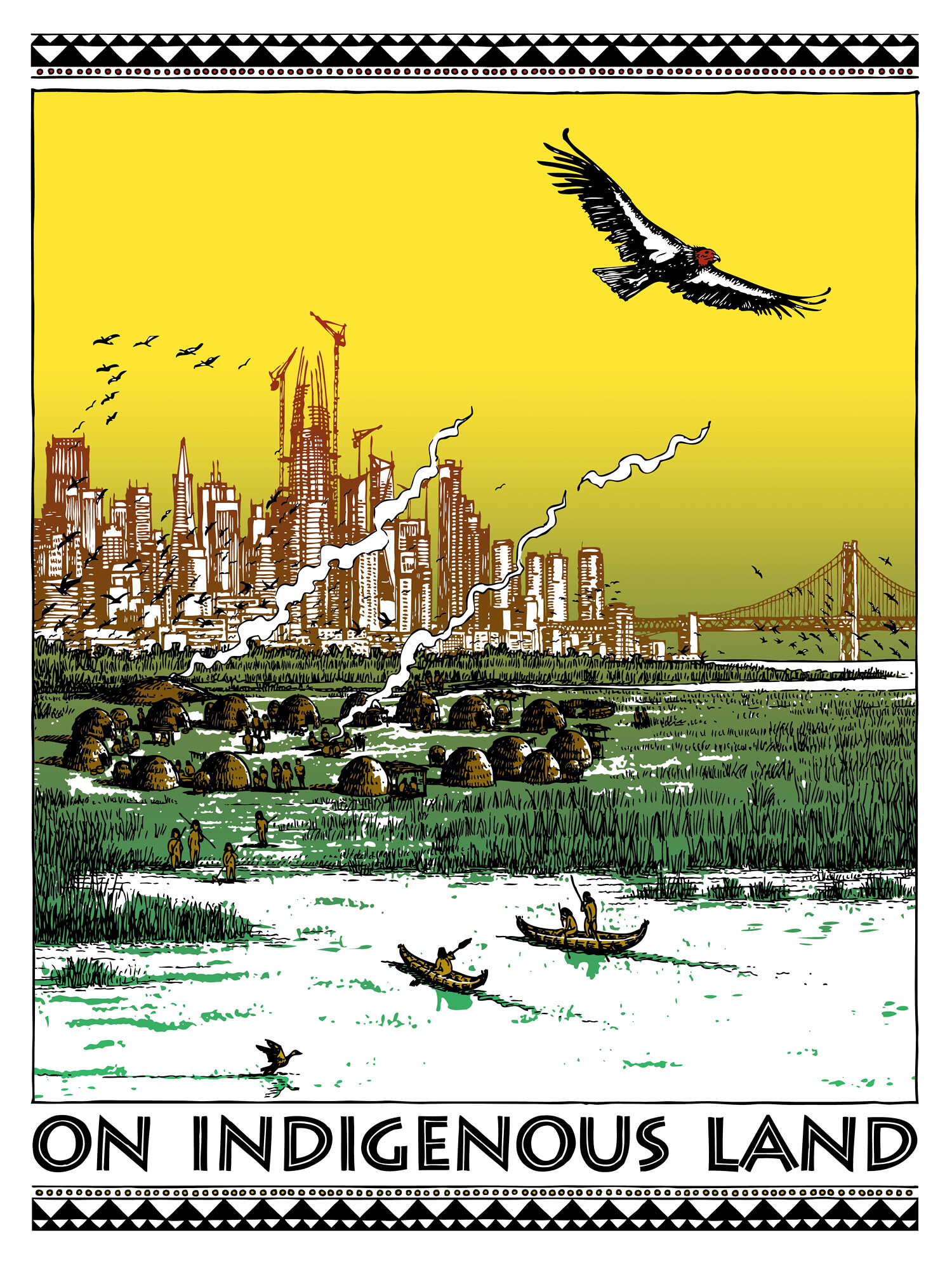

According to its pre-eminent historians and theorists, settler colonialism is a structure that shapes the ongoing development of settler colonial societies.1 As the memorialization of October 12 indicates, however, these societies tend to understand and valorize settler colonialism as a historical moment in their distant past—a moment defined by appropriation, dispossession, and violence that are eclipsed and legitimized as settlers develop the land, water, and plant and animal lives they have taken from the Indigenous peoples who sustained and were sustained by the preceding. And thus we—settlers and Indigenous people alike—live in a settler colonial present. We daily inhabit and occupy Indigenous land, some forcibly taken and some never ceded.

Architecture, with its deep implications in property and capital derived from settler colonial processes, condenses the tensions, contradictions, disavowals, and betrayals of settler colonialism. And yet, discourse on settler colonialism has been largely absent from the architectural discipline. This absence is productive in settler colonial contexts—it allows the discipline to most effectively serve the interests of capital and its emissaries. Indeed, in its hegemonic professional and pedagogic forms, architecture was and remains a product, instrument, and memorial of settler colonialism. Attempts to “decolonize the curriculum” that omit these constitutive relations are complicit with them.2

Settler colonialism is therefore not simply one topic to add to the architectural curriculum—in settler colonial societies, settler colonialism arguably defines every part of the architectural curriculum, and even what counts as a curriculum itself. Approached in relation to the settler colonialism that it advances, legitimizes, and celebrates, then, architecture opens onto new registrations of the settler colonial present and decolonizations of its histories and possible futures.

In Patrick Wolfe’s well-known words, “settler colonizers come to stay: invasion is a structure, not an event.” See Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journalism of Genocide Research 8, vol. 4 (2006).

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang have termed these evasions as “settler moves to innocence” that reconcile settler guilt and complicity. Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, Society 1, vol. 1 (2012): 1–40.

The Settler Colonial Present is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Settler Colonial City Project, with the support of the Department of the History of Art and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.