The Universal Hall in Skopje is one of the city’s main landmarks, and has stood as a symbol of global solidarity for over sixty years. Following the disastrous 1963 earthquake, it was the first building of public and cultural character built as part of the reconstruction efforts. It was designed to host the so-called “Meetings of Solidarity,” annual, week-long, cultural and sports festivals to celebrate the reconstruction of the city.1 The building was built with funds that were pooled together from thirty-five countries, mainly countries in Asia and Africa. These countries, along with Yugoslavia, were part of the Non-Aligned Movement, which defied the East-West geopolitical divisions of the Cold War.

In the wake of the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, this landmark building faced an uncertain future. After a decade of being underfunded and poorly maintained, it was closed in 2015 due to structural damage and, shortly thereafter, part of the roof collapsed. Following numerous failed competitions for renovation and rebuilding, escalating cost estimates, and contests over custody and ownership between the city authorities and the North Macedonian Ministry of Culture, the building currently stands in limbo. Since Skopje’s recent winning bid to become the European Capital of Culture for 2028, however, the Ministry of Culture has pledged to renovate and reconstruct the building. It remains to be seen if that will be enough to transform one of the most symbolic buildings in Skopje into a landmark of European culture.

The Earthquake

In the early morning of July 26, 1963, an earthquake hit the city of Skopje. More than 1,000 citizens lost their lives and around 70–80% of the city fabric was destroyed or ruined beyond repair; nearly 75% of inhabitants—approximately one hundred and fifty thousand people—were left homeless and displaced.

Organized through the United Nations, what followed was one of the most comprehensive rebuilding efforts in post-war history. Skopje became an example of international cooperation and global solidarity at a time when the world was facing the Cuban missile crisis and bracing for the possibility of a nuclear catastrophe. In this light, the rebuilding of Skopje was presented both by the UN and in the media as a solution to the problems “of the troubled world.”2

The most explicit statement of these aspirations for humanity came from the President of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito, when he addressed the UN General Assembly on October 22, 1963:

We feel … this broad display of international solidarity also reflected the desire of the overwhelming majority of peoples throughout the world to prevent the far greater catastrophe which a nuclear war would bring upon humankind. At the same time, this display of solidarity expressed, in its own way, the strivings towards new, more humane relations in the world, of relations wherein the welfare of each and every nation would be in the interest of the world community as a whole.3

International Solidarity

News about the earthquake immediately spread beyond the borders of the Yugoslav Federation, evoking a strong response and activating the international community. In response to Tito’s appeal to foreign governments and the International Red Cross—which he continued to make for an entire decade following the catastrophe—aid from over eighty countries began to arrive in Skopje. Such expressions of sympathy and help were not entirely new to the international community at the time; however, in the case of Skopje, they exceeded any global precedent in their scope and in the significance associated with them.

The character of these gifts changed over time. Starting with blood plasma and blankets, building materials and prefabricated structures of various origins and typologies began to arrive soon after. These were often accompanied by teams of engineers and workers who provided expertise and labor. Starting in 1964 and for five years after the earthquake, buildings with significant architectural ambition were built as well, either as direct donations from various countries or through combined financial resources. Numerous prefabricated houses, schools, clinics, hospitals, sports facilities, and many other buildings each had their own narrative of sympathy, humanism, and solidarity.4 Among these, the Universal Hall was a unique case created by pooling donations from thirty-five countries.

The Reception of Solidarity

The gifts that came to Skopje were much needed and highly appreciated, both by the local authorities and by the citizens of Skopje. Statements of appreciation, deep gratitude, and reciprocal obligation were ubiquitous in speeches, written documents, and the many short documentary films dedicated to Skopje’s reconstruction. Furthermore, the Assembly of the City of Skopje made an effort to meticulously archive and commemorate each donation, regardless of its origin, size, and character.5 Diverse in terms of scale but truly global in character, gifts came from the leaders of the two main blocks, USSR and USA, countries belonging to the East or the West respectively—Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Great Britain, France, West Germany, etc.—and from many Asian, African, and South American countries, including Egypt, Ghana, Mali, Algeria, Liberia, Iran, Pakistan, Syria, Mongolia, etc.

With the idea of commemorating the earthquake and bringing together the people, organizations, and countries that, in various ways, had helped Skopje since, the Assembly of the City of Skopje organized a cultural and sports event, a “Meeting of Solidarity.” The first “meeting” took place from July 26 to August 2, 1964, on the first anniversary of the earthquake, and was then held annually for over a decade. To the world, these events presented gratitude for the help that was given, as well as the achievements and the perseverance of the city and its people. For the citizens of Skopje, these “meetings” were meant to raise spirits and show that Skopje was not alone in its efforts. The first event contained an eclectic cultural program, including folk and youth ensembles, classical orchestras, choirs, jazz concerts, and other performances from Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, France, Denmark, USA, Algeria, etc. With most of these programs happening outdoors or in adapted sports facilities, it quickly became evident that the city needed a dedicated space, a large auditorium, for the next Meetings of Solidarity.

The Universal Hall

Despite the terrible disaster, what characterized the post-earthquake period was the immense and, at times unrealistic, optimism; the unbreakable faith that the city would be rebuilt again, “more glorious than ever before.”6 In early 1964, coinciding with the urgent need to provide housing, the Fund for Aid and Reconstruction of Skopje allocated the necessary financial assistance to build a large performance hall that could be used for various cultural and sports events and would serve as a symbol of solidarity.

In the process of distributing financial assistance, the Fund for Aid and Reconstruction followed a few criteria, first and foremost being the wishes of the donor. Where no such wishes were clearly expressed, however, or when financial donations were more modest, funds were often pooled together. The Universal Hall was funded by thirty-five different countries from donations that were “smaller in quantity and thus insufficient for the construction of individual buildings.”7

The decision to pool together financial aid to build a permanent landmark, instead of spending it on the more prosaic needs of the city, in a way represented a “counter-gift,” in which the deep gratitude and the moral obligation of the city and its people were inscribed.8 The building was therefore not only dedicated to the many cultural events to come, but was also a genuine symbol of international solidarity in the reconstruction of Skopje.9 With most of the donating countries located in Africa or Asia, the building was also an opportunity to demonstrate and emphasize Yugoslavia’s political and cultural relations with current and prospective members of the newly established Non-Aligned Movement.10

Construction blueprints of the Universal Hall by the company Technoeksportstroy from Bulgaria, 1964. Source: The Archive of the City of Skopje, 1964.

Construction blueprints of the Universal Hall by the company Technoeksportstroy from Bulgaria, 1964. Source: The Archive of the City of Skopje, 1964.

Construction blueprints of the Universal Hall by the company Technoeksportstroy from Bulgaria, 1964. Source: The Archive of the City of Skopje, 1964.

Construction blueprints of the Universal Hall by the company Technoeksportstroy from Bulgaria, 1964. Source: The Archive of the City of Skopje, 1964.

The Universal Hall was modelled on a prefabricated structure that had already been built in 1962 as the State Circus in Sofia, Bulgaria, designed by the Stankov brothers and their sister, Kostadinka Stankova-Mutafova.11 In April 1964, the Fund appointed the trading company “Tehnometal Export-Import” from Novi Sad, Serbia, to purchase the complete prefabricated structure from the manufacturer “Tehnoeksportstroi” in Sofia. The negotiation process and purchase was straightforward, and the agreement for a multi-purpose performance hall with a total capacity of 1,800 seats was signed in Sofia on July 11, 1964.12

A prominent and easily accessible location was chosen for the building along one of the city’s main traffic arteries, the Partizanski Odredi Boulevard. Construction started in August 1964 and was scheduled to end in June 1965. Around seventy construction workers from Bulgaria worked on the assembly of the prefabricated structure, some of whom were already located in Skopje and engaged in other elements of the city’s reconstruction. Still unfinished, the building was used for the first time in July 1965, hosting the second Meeting of Solidarity’s cultural program.

Being one of the first public buildings erected in Skopje after the earthquake, the Universal Hall hosted nine events with approximately 13,300 visitors before the end of 1965. After a thorough technical inspection was conducted in December 1965, the building was officially opened on January 10, 1966, with a performance from the famous Belgrade theater troupe, Atelje 212. For decades following its completion, the Universal Hall served as the most significant auditorium space in the city. Alongside the prefabricated structure of the Macedonian theater (which has a much smaller capacity), the Universal Hall has hosted many different types of events, including symphony and philharmonic concerts, opera performances, jazz concerts, folklore events, theatrical plays, and even smaller sporting events. The notion that it was built to commemorate the humanitarian action of donors, and the fact that it was so intensively used by citizens so soon after the earthquake, gave the Universal Hall great symbolic value and made it an icon within the city.

Afterlife

Initially greeted with optimism, the process of independence following the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s led to a long, troublesome, and somewhat uncertain period of transition for Macedonia. Along with many challenges linked to economic and social restructuring, political change also became a catalyst for dynamic and dramatic spatial transformation. The city of Skopje dismantled many urban planning regulations and began to emphasize the individual, as opposed to the public, as the driving force for urban development. After a period of economic stagnation, since the early 2000s Skopje’s socialist modernist heritage has become a symbol of an “unfavorable” past that needs to be replaced or rewritten in order to make way for a new, national capital. This process of cultural and architectural “re-rationalization” has resulted in the construction of numerous new, eclectic, neoclassical buildings, as well as the brutal disfigurement and alteration of historical modernist ones.

Within this turbulent context, the Universal Hall was left to a slow decay. Without the financial support for a substantial renovation, its structure and materials deteriorated until it hosted its last performance in March 2015. Several days afterwards, sections of the suspended ceiling suddenly collapsed over the auditorium, and the building was declared unsafe for use. The dereliction of this symbol of global solidarity did not provoke an immediate reaction. On the contrary, for nearly a decade, the same rhetoric of Skopje as a symbol of international solidarity has persevered, despite the fact that it has lost one of its most symbolic gifts.

Even while the Universal Hall was still in use, the idea that the city needed a larger auditorium hall was discussed by city authorities.13 But structural analysis of the existing building, completed by the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Skopje around 2012, showed that the original structure could not withstand additional loads, so the idea for reconstruction and enlargement was abandoned.14 In 2013, the building was proclaimed dilapidated and incapable of meeting contemporary requirements in terms of capacity and standards (accessibility, safety, energy efficiency, etc.). Finally, in the same year, the mayor of the city at the time, with support from the Ministry of Culture, announced an architectural competition for a new Universal Hall.15

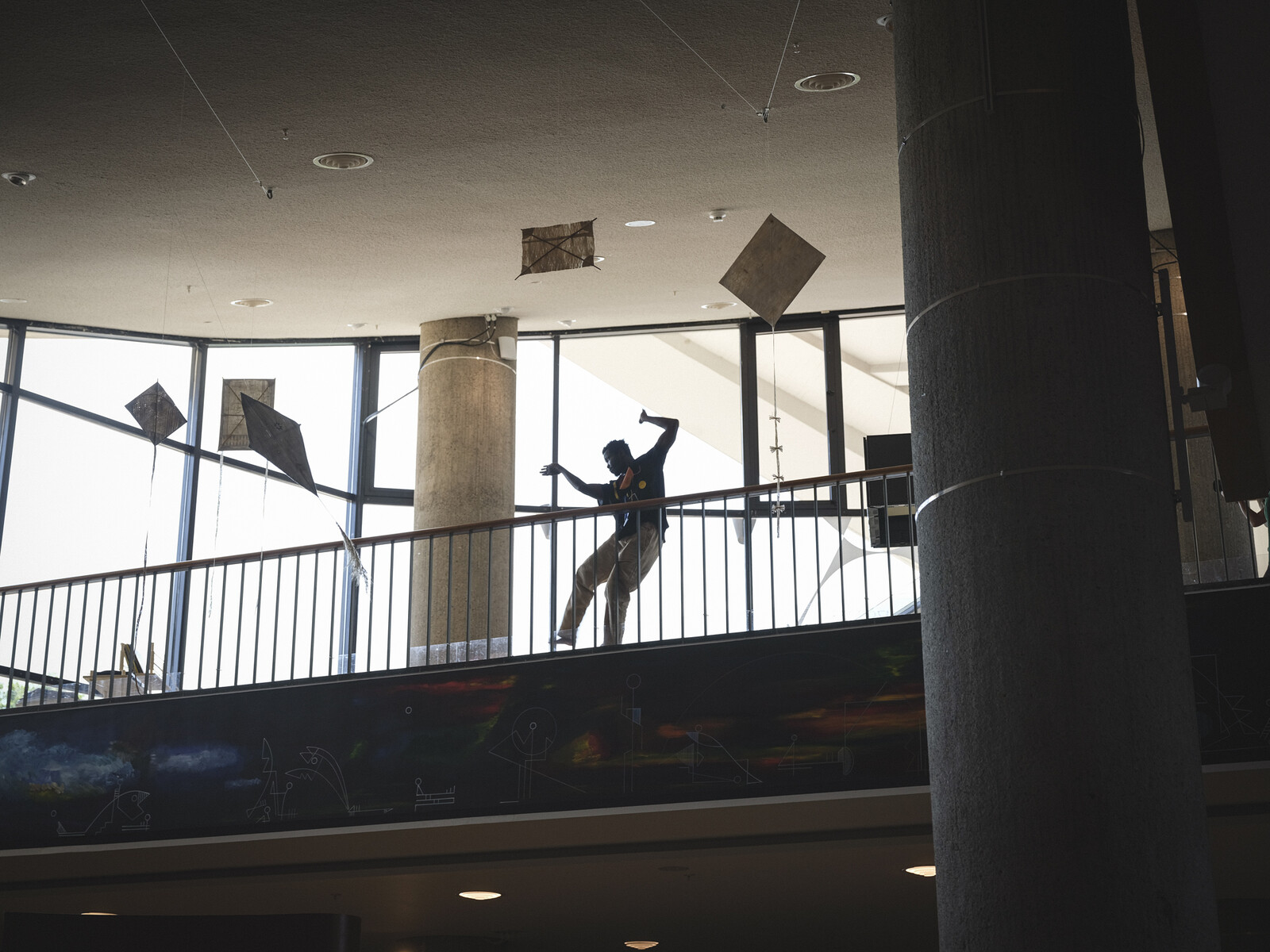

The Universal Hall remains closed and under construction. Photo: Mila Gavrilovska, 2023.

The Universal Hall remains closed and under construction. Photo: Mila Gavrilovska, 2023.

The Universal Hall remains closed and under construction. Photo: Mila Gavrilovska, 2023.

The Universal Hall remains closed and under construction. Photo: Mila Gavrilovska, 2023.

The new building was to be built in the same location but with significantly enlarged auditorium spaces, auxiliary spaces, and administrative offices. Competition entries were awarded, and the winning proposal began to further develop their plan.16 However, it soon became apparent that a significant enlargement of the program was impossible. The winning proposal was too extravagant, expensive, and somewhat impossible to build. In 2015, the city aborted the project and announced that the existing building would be reconstructed (and again, enlarged).17 Five years later, in July 2020, the City of Skopje announced another competition, this time for a (memorial) park on the site of the Universal Hall.18 This new competition required an open summer stage as a tribute to the original use of the space. Alongside this, and in acceptance of the impossibility of building a space with greater capacity in the same location—which is within a residential neighborhood that has become much denser since the 1990s—the city announced in 2020 that it would build a new concert hall on the outskirts of Skopje.19

Although the idea of a “new” Universal Hall has been presented to the public since 2013, in 2020, the idea of demolishing the historical structure was met with fierce public opposition and intense debate. The city withdrew its proposal once again, and the decision was eventually made to reconstruct the existing building.20 In March 2021, the mayor publicly promoted the project for reconstructing the Universal Hall by dedicating 120 million denars (approximately 2 million euros) to the reconstruction process from the Budget of the Government of the Republic of North Macedonia.21 The main goals of this reconstruction project were to retain the existing location and to rebuild as close to the original shape of the building as possible, all while introducing a new structure, redesigning the interior to make it more comfortable, and improving the building’s thermal characteristics. Reconstruction started right after the mayor’s announcement.

This proposal addressed many public concerns. However, with the change of the local government in 2021, construction stopped, and the building once again found itself in the media, its future undetermined. Since then, however, the building has been transferred from the authority of the City of Skopje to that of the Ministry of Culture.22 With the announcement that Skopje will be the European Capital of Culture for 2028, we might again be able to hope that there will be a positive outcome and better future for one the city’s most symbolic public buildings.23

Many individuals, ensembles, theater groups, contemporary and folk-dance groups, orchestras, and artists from Yugoslavia and many other countries who helped the city took part. Contests in athletics, bicycling, swimming, water polo, and gymnastics were also held. Ivan Toševski, Your Aid to Skopje: July–September 1964 (Skopje: Gradsko sobranie na Skopje, 1964), 16.

United Nations Development Programme, Skopje Resurgent: The Story of a United Nations Special Fund Town Planning Project., ed. Derek Senior (New York: United Nations, 1970), 52.

United Nations General Assembly, “Official Records of the General Assembly, Eighteenth Session, 1251st Plenary Meeting.”

The immense quantity of help, both material and financial, demanded maximal centralization and control of the inflow and its distribution. In September 1963, a federal law was passed and a new body was created—The Fund for Aid and Reconstruction of Skopje. The law abolished the previous Federal Fund for Reconstruction, transferring all the rights and obligations to the city of Skopje and the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. The law stipulated that the fund should distribute the means according to the Program for Reconstruction of the City of Skopje, adopted by the City Assembly.

Much of this archival material was published in successive series of small booklets entitled Vaša pomoć Skopju/Your Aid for Skopje, distributed locally but also periodically delivered to the countries and institutions who contributed to the city’s renewal. The first publication was issued immediately after the earthquake, covering the period from July to September of 1963.

United Nations Development Programme, Skopje Resurgent.

In the process of distributing the financial assistance, a few criteria were followed, first and foremost being the wish of the donor. Where no such a wish was expressed, and especially in cases when the individual financial assistance was more modest in quantity, the funds were pooled together. Fund for Aid and Reconstruction of Skopje, Draft Program for implementation of the foreign assistance for Skopje, Skopje, September 1964, from the private archive of Kocho Bitoljanu.

In the documents issued by the Fund for Aid and Reconstruction of Skopje, the “moral and political obligation” of the city and its authorities was often mentioned.

Like many other buildings that were received as donations or were built with foreign assistance, as long as it was in use, the building had a plaque at the entrance stating the names of the donor countries: “This Universal Performance Hall was built with the help given to Skopje by citizens, humanitarian organizations, and the governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cambodia, Canada, Ceylon, Chile, Cuba, Cyprus, Guinea, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Lebanon, Liberia, Luxembourg, Mali, Monaco, Mongolia, Morocco, Nigeria, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sudan, Senegal, Syria, Turkey, Tunisia, Uruguay, Yemen, as well as the foreign tourists who found themselves in Macedonia on the day of the catastrophe. This building will remain as a permanent symbol of international human solidarity in the reconstruction of Skopje after the catastrophic earthquake of July 26, 1963.”

The Non-Aligned Movement was founded on the Brijuni Islands in Yugoslavia in 1956 and was formalized by signing of the Brijuni Declaration. In 1961, the first Non-Aligned Conference, the first official summit of the movement, was held in Belgrade, capital of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The original building was destroyed by fire in the 1980s.

For the Skopje building, the initial capacity was slightly reduced in order to be more comfortable and provide better acoustics. As occurred in other cases as well, the City of Skopje funded the other design phases—the micro-urbanism, outdoors infrastructure, landscape design etc.—which were completed locally, mainly by the Construction Companies “Makedonijaproekt” and “Granit.”

This was discussed in particular in “Strategy and Action Plan for the Cultural Development of the City of Skopje for the Period 2012-2015.” See ➝.

The former mayor, Petre Shilegov, referred to a relevant study in an interview in 2020, arguing that the Universal Hall needs restoration and could not withstand an increase of the existing structure. The study mentioned is Irena Karevska, “With the Money Thrown at Failed Projects, Universal Hall Might Have Been Renovated by Now,“ 360 degrees, July 29, 2020, ➝.

Over six hundred thousand euros have been spent so far on architectural competitions alone. Srdjan Stojanchev, “Universal Hall: Nobody Has Gotten Further Than a Project,” Radio Free Europe (Macedonia), July 29, 2020. See ➝.

“The Design for the New Universal Hall Has Been Chosen,” Porta3, December 4, 2013. See ➝.

This time, full technical documentation was completed by the Civil Engineering Institute of Macedonia and the reconstruction was estimated to cost approximately 15 million euros.

Anna Torevska, “A Modern Park will be Built on the Site of the Universal Hall,” Kanal 5, July 27, 2020. See ➝.

“Shilegov for Universal Hall: Let’s Build a New Symbol of the City in a New Location,” 360 degrees, August 25, 2020. See ➝.

A. Anthevska, “City of Skopje Starts Reconstruction of Universal Hall. Shilegov Says it will be Ready for Concerts in Autumn,” SDK, October 29, 2020. See ➝.

“Zaev and Shilegov Presented the Project for the Reconstruction of the Universal Hall,” March 1, 2021. See ➝.

In July 2023, the Council of the City of Skopje accepted the initiative to temporarily hand over the credentials for the reconstruction of the Universal Hall to the Ministry of Culture. “The Ministry of Culture has formed a team that will work on the Universal Hall,” Sitel, September 28, 2023. See ➝.

Silvana Kocovska, “Skopje Named 2028 European Capital of Culture,” MIA, September 20, 2023. See ➝.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.