“The Poor Helping the Poor”

If it was not because of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), many people, including the Chinese, would have continued to forget the history of foreign aid in Mao’s China. While there are formal resemblances between the two, there are crucial differences. Retelling the Maoist Chinese perspective on aid does not simply add a missing piece to the puzzle of global gifting. Socialist China under Mao was an inner other in the global socialist sphere. Maoism, despite sharing commonalities with other official socialist ideologies, staged itself more as a critic of them, especially of Soviet ideology. Such critique was not an external judgement, but a form of self-critique, one that re-evaluated the Soviet socialist elements that had been internalized in China. With its agenda of “continuous revolution” to challenge de-politicized institutionalization, Maoism resonated with Western New Left and Third World revolutions and became an essential participant of the “global sixties.” The confrontation between China and the Soviet Union/bloc during this time was ideologically charged by the question of how to get socialism right, and the difference between their respective aid practices illustrated this.

China was a significant beneficiary of Soviet aid in the 1950s, which enabled China’s first five-year plan (1953–57) and laid its industrial foundation. But China was quickly threated by the Soviet Union when Khrushchev abruptly cut off that aid in 1960 as a way to demand China’s obedience. This event triggered the historic Sino-Soviet split. Mao and his comrades realized that “socialist aid” was not necessarily insulated from the inequality, condescension, and domination that characterized aid under capitalism. Soviet aid thus came to be seen by the Chinese as little more than a debt. In response, China worked arduously to pay it off one year ahead of schedule, and insisted on including the interest. The Maussian term “hau” refers to the spiritual significance and power of a gift that subjects the recipients to certain rules. China’s repayment purposely deprived the Soviet aid of any possible hau, implying it was just business.

This episode significantly shaped China’s foreign aid philosophy. During his historic visit to ten new African nations in 1963–64, Chinese Premiere Zhou Enlai announced China’s Eight Principles of Foreign Economic and Technical Assistance. Its first principle marked the tone: “The Chinese government always bases itself on the principle of equality and mutual benefit in providing aid to other countries. It never regards such aid as a kind of unilateral alms but as something mutual.”1 Zhou’s principles were not only targeted at potential aid recipients, but also at the givers.

It is reductionist to either equate Maoist aid with power games or view it as simple developmentalism. Rather, historically speaking, Maoist aid was an act of recognition through passionate and committed giving, embodied through resource flows between newborn, distant, and previously unfamiliar political communities. Recognition here is not only about legal status in international law, but also, philosophically speaking, about the way an epistemological and agentive subject gains self-consciousness through mutual recognition from/to the collective personalities of political communities. The traditional Chinese cosmology of tianxia, literally “all under heaven,” does not differentiate between inner and outer spheres, in which the “other,” in an ontological sense, is absent. Mao’s passion for internationalism and world revolution contained a historical solution to the collapse of tianxia that had been ongoing since the mid-nineteenth century. In a historical moment of learning about China’s new self, together with the crystallization of “new others,” China viewed aid as basic form of co-existence with political communities elsewhere in equal positions.

Without recognizing this, it is difficult to explain why Maoist China participated so intensively in foreign aid when it was itself in such a weak economic and technical condition. In 1960, China established its ministerial agency of foreign aid. The country spent an average of 5% of its national budget per year on aid during the 1960s and 70s.2 In 1973, this reached 7.2%,3 equaling 2.05% of its Gross National Income (GNI).4 This is enormous compared to the average percentage of GNI spent on aid by other countries during the same period, such as 0.38% in OECD countries and 0.67-1.3% in the Soviet Union.5 Such huge expenditures realized massive projects around the world. More than 1,100 “turn-key” projects (officially termed “complete-plant projects”) were completed by 1985, mostly in Africa and Asia. The vast majority of these were categorized as “productive architecture,” namely, industrial and agricultural construction, while only a few went to eye-catching civil architecture, such as theaters, stadiums, and collective apartments.6 The purpose of these industrial spaces was to improve productivity and strengthen the local working class. Even in Tanzania, the country with the highest density of Mao-era Chinese aid projects, none were officially counted as civil architecture, not even the Tanzania-Zambia Railway/TAZARA Terminal, which is a de facto monument.

Neoliberalism hit Africa in the mid-1980s and led to an enormous abandonment and dereliction of Chinese industrial aid projects, the remnants of which are barely recognizable today. During fieldwork in Tanzania, I often had to rely on satellite maps and the few descriptions of the projects (location, orientation, size, floor plans, etc.) I could find printed in old Chinese reference books to identify them. Even locals cannot recall what is what and where they are. There is a great historical amnesia and confusion around this history.

In Zanzibar, I stood in front of the Mechanzani residential project—a large complex of collective apartments built by East Germany in the late 1960s—and an old man mistakenly assured me that it was a Chinese construction. On the other side of the island, at the entrance to a building that I knew was formerly a China-built cigarette factory, a plaque read, “USAID: From the American People.” My interviewee, a retired local engineer, later explained that the factory had been abandoned and eventually adopted as a workspace for the American aid program. Not far from there, what was originally a leather factory built by the Chinese in 1967 is now a warehouse for a newly arrived Chinese construction company. Ironically, the Chinese employees were unaware of who had built the space they were taking over. Nowadays, such stories of architectural vicissitude can easily go viral on Chinese social media, becoming a target of sensational accusations of Mao’s irrational decision-making and the waste of taxpayers’ money. The public’s incomprehension of Mao’s logic of aid often leads to anger and a sense of betrayal.

Back then, China was undoubtedly a poor country, with an even lower income per capita than many of the countries it was giving to. But in Maoist philosophy, the poor have their own way. China’s aid was characterized by what Mao termed “the poor helping the poor” (“qiong bang qiong”). Mao praised the potential of the poor as a political category and asserted that the liberation of the poor is the liberation of the world. Such liberation only came from cooperation and mutual aid, rather than charity from the rich to the poor. Being a giver who is poor contains a dimension of sacrifice: only sacrifice can create an obligation without calculating the reward. Sacrifice negates the conventional flow of resources from the rich to the poor, from the North to the South, and from the (former) metropolis to the (former) colonies. This flow seems just and natural to many, but it does not reduce inequality; it only legitimizes it. The logic of sacrifice, however, implies that the less you have, the more you should give, in order to negate the interpellation of the poor as the recipient. In this way, the poor can be truly radical, in desiring to desire, desiring better, desiring more, and above all, desiring differently. For their own emancipation, the poor must dare to become inappropriate and anachronistic givers, to interrupt the normality of the ruling rich as distributors. Like the lyrics of The Internationale, “We are nothing, now let’s be all”: nothingness opens the gateway to everything.

Accordingly, giving to the poor counter-intuitively requires the avoidance of any generosity, because it tends to evoke admiration in the recipient, and thus expectations of repayment. In such a relation, giving is potentially taking: the giver will either become a creditor or gain dominion over the poor who cannot repay except by forfeiting the debt and renouncing their social status. In other words, giving to the poor can only work in the case of nonreciprocal giving. The way Mao accomplished this was to interpret aid not as an action, but as a reaction, annihilating the possibility of further reciprocity. Like the first rule of Zhou’s Eight Principles implied, Mao and his comrades always told the “recipients” that they had helped the Chinese first, for their revolution had weakened imperialism, and therefore China’s aid was already a reciprocation for their own gift. Non-reciprocal giving is therefore not giving from “A” to “B,” but rather a scenario of “A” giving to itself, in which “B” is not a receiver but a mediator who helps accomplish the self-giving of “A.” Within this context, “B” receives something from “A” in order to help them, but does not owe “A” anything in return. The Maoist “gift,” intentionally left incomplete, always appears as a counter-gift that does not require reciprocity, for it is itself the closure of a reciprocal relation.

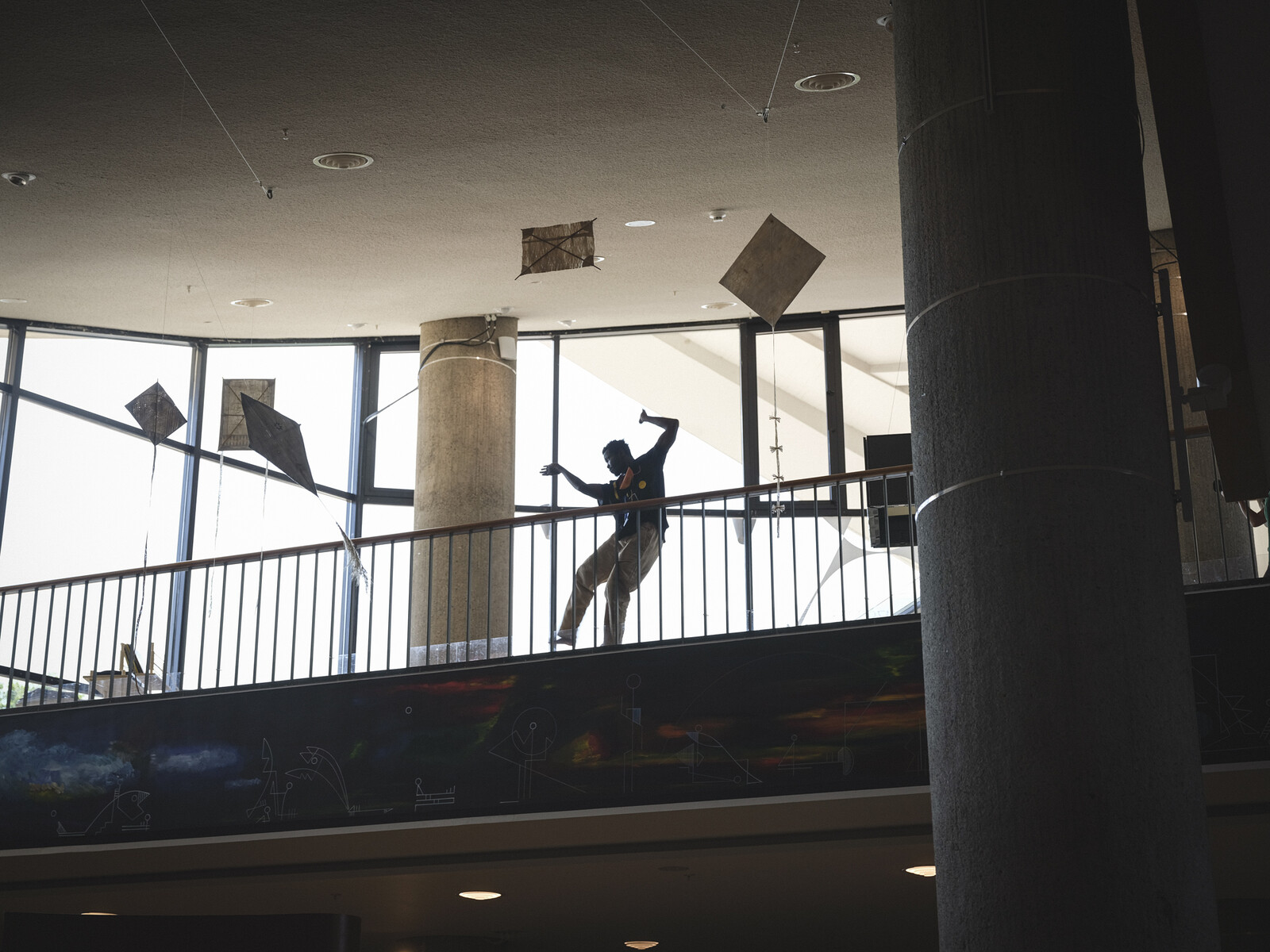

Friendship Textile Factory, dining hall and the office, Tanzania. Photo: Ye Liu.

Types and specifications for staff dormintories at Friendship Textile Company in Tanzania.

The entrance courtyard of the Friendship Textile Factory, Tanzania, completed in 1968, was often used as a public space for mass rallies. A. M. Babu, an outspoken Marxist in Nyerere’s Government and author of African Socialism, or Socialist Africa (1982), encouraged the workers there to “fight against exploitation.” The factory office building stands behind him, with multi-layered shading, a typical design in the tropics. The Nationalist, July 24, 1969.

Friendship Textile Factory, dining hall and the office, Tanzania. Photo: Ye Liu.

Giving Without Reciprocity

The idea of a subject giving to itself reminds me of a fable from ancient China, whose popular version goes as follows. The king of Chu returned from a hunt to find that he had dropped his exquisite bow. His followers asked for orders to go back and look for it, but the king said, “Never mind, leave it to any finder in my kingdom. A Chu man lost it, and another Chu man received it; nothing is lost.” Confucius commented on the king’s words, “What a merciful king, but he could be better by dropping the word ‘Chu’: a man lost it, and another man received it; nothing is lost.” Lao Tzu, the originator of Taoism, too, joined the discussion, remarking, “Confucius is right, but he could be even better by dropping the word ‘man’: lost, received; nothing is lost.”7 From today’s perspective, the king of Chu resembles a tribalist, Confucius a humanist, and Lao Tzu a universalist. In the eyes of universalism, the bow, which symbolizes valuable resources, is not given from one subject to another but from a Hegelian substance (i.e., the universal whole) to itself. Yes, giving yields a return, but it is no longer from the recipient; giving and receiving occur at the same place. Aid as such would be fundamentally free from any possible hau, patronage, indebtedness, and inequality, since the giver is nothing more than the temporary personification of universal substance. Such aid is simply a mini-avatar of the self-movement of the universe. For Mao, nonreciprocal giving practiced not only the “proletariat internationalism” in form, but also the law of evenness that he considered universal and objective in substance.

Kojin Karatani offers a similar perspective when he interprets Marx’s political economy not from the conventional mode of production but from the mode of exchange. Apart from compulsory reciprocity through custom (exchange mode A), redistribution/plunder through authority (exchange mode B), and market exchange through abstract equivalency (exchange mode C), Karatani envisions a fourth mode of exchange as an “associationism,” in which people give but with freedom. Karatani sees this fourth mode as the economic base of communism.8 For him, exchange mode “D” is not wishful thinking, but based on a human impulse to survive together that may be latent and continually repressed, but never disappears. The essence of the communist movement is therefore to actualize the return of this repressed potential that only becomes conscious of itself through the experience of capitalism. In this sense, socialism is itself an expression of the self-consciousness of modernity that is firstly incarnated in capitalism. The more profoundly modern socialism is, the more it might manifest itself in archaic forms, as shown in Maoist aid policy. Marx’s “primitive communism” is less a historical reality than a retrospective signifier for dialectical return. The spirit of socialist giving is best summarized in the words of Marx himself in the Critique of the Gotha Program: “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.”9 That is, I give, and I receive, and there is no inherent connection between the two.

To achieve this freedom from reciprocity, Maoist givers had to be highly skillful. Only a tiny percentage of Mao-era aid was given as grants; most came in the form of interest-free or low-interest loans. Loans as an aid mechanism were used by everyone at the time, even the Soviet Union.10 The Chinese government negotiated formal loan contracts with foreign recipients. The interest rates of these loans were considerably lower, and repayment periods were considerably longer, than in other socialist aid programs.11 But the real secret lay in China’s internal budgeting mechanism, which only listed aid expenditure on their annual budget statements, not the income from its repayment.12 That is, China did not account for its loans to be repaid, which also meant the debt could not be forgiven. Indeed, when reflecting on the Maoist loaning policy, a present-day Chinese senior official complained that the chances of receiving repayments were “extremely low,” since the terms of the so-called loan were “no different financially to grants.”13 Grasping the dialectic relationship between the equal and unequal, Mao’s approach to aid appropriates the means of equivalent exchange, a formal equality, in order to approximate a result of substantive equality.

In 1967, Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda expressed his gratitude to Mao over the TAZARA agreement. He heroically promised that the Zambians would continue supporting southern African freedom fighters in return for China’s help. However, Mao answered that there was nothing to return since the assistance was China’s “obligation.” Immediately afterward, Mao uttered his famous statement, “China cannot liberate itself until the whole world is liberated,” echoing the classic assertion that the proletariat can only liberate itself by liberating class society per se. Mao continued with some much-less quoted, but just as important words: “it also applies to you.” With this, Mao implied that Zambians’ support to African liberation movements was not an option that China made possible, but an obligation they had themselves. This is, after all, precisely what obligation means—that there is no choice; it is a recognition of necessity. In that moment, Mao believed that the Zambians should neither feel indebted to the Chinese nor feel superior to African freedom fighters, for all were equally fulfilling their respective obligations, no matter if that was through giving or taking. If they acted otherwise, the revolution would be in vain. Obligation, here, is true freedom.

In 1965, an investigation took place over some inspection reports of Chinese foreign aid. These reports point out that several material items supplied for foreign aid were of inferior quality than foreign trade commodities, and thus a breach of diplomatic conduct. The investigation concluded that the problem was neither reckless production nor sensational class enemy sabotage. Instead, it was simple: commodities are sold on the international market, and officials can only select things that are competitive and profitable. Aid, however, is need-based and an obligation, for which the Chinese have to give what they have according to the recipients’ demand, with little room for bargain.14 The investigation ended up calling for better institutional coordination in material supply between the trade and aid sectors to make sure the aid channel has higher priority, which was entailed by the nature of its obligation.

Such urgency and discipline imbued the Maoist aid with sense of militancy, performing like comrades-in-arms backing up each other in a trench. Indeed, foreign aid practitioners were called “foreign aid fighters” (援外战士yuanwai zhanshi). Those who died on duty during an overseas aid project even became “martyrs”; from the 1950s to the 1980s, there were 585 of these “martyrs.”15 Notably, as a comrade-in-arms, China was not alone in this spirit of sacrifice, which appeared to varying degrees in the poor but daring political subjects of the Third World. Guinea fought to contribute 1% of its national budget to the South African liberation movement.16 Tanzania called for “trade union loyalty” among the non-aligned countries to prevent them from being divided by short-sighted national interests.17 And while it received aid from others, Zanzibar gave food to Kenya and Pakistan.18 This was a rare moment in modern history when the poor dared to desire in the role of givers.

Resistance to Sacrifice

Still, as the 1965 investigation shows, sacrifice is rarely smooth. To what extent is sacrifice even practical? Is prolonged frugality and discipline sustainable for a people, a nation? Can the framework of the modern nation-state continue to function in spite of unilateral outward transfers of resources? In China, while Mao was alive, the charismatic revolutionary could pedagogically, or Machiavellianly, convince the masses that it was right to provide aid to others (just like in his famous slogan “it is right to rebel”) by offering them not material benefits but hope and a sense of emancipation. Mao presented the Leninist “proletarian internationalism” of “[bearing] the greatest national sacrifice” as a sublime way of life. Sacrifice can be heavy, but salvation is ever-present, even beyond the duration of individual lives. But sacrifice is not merely an ideal. The amount of aid expenditure fell slightly in the year before Mao’s death (1976). Within three years, it had fallen dramatically, to less than 1% of the national budget, then dropping below 0.1% from 1988 onwards. In 2019, it was 0.047%.19

The willingness and determination to sacrifice does not guarantee its efficacy. After all, sacrificial giving in the form of aid projects does not transfer an abstract package from one to another, but always involves material, financial, bureaucratic, technical, intellectual, and human resources. In terms of architecture, an experienced aid project reviewer in Beijing told me that the real challenge of aid is not professional capacity but “foreign affairs,” namely, negotiation. The process of architectural design, in this sense, replicates the relationship between aid givers and receivers. Although the architect (i.e. the Chinese, or the givers) makes the blueprint, the client/owner (i.e. certain African or Asian countries, or the recipients) determines whether it is adopted or not, and how to receive/accept the gift. The architect here plays the role of the salesperson, where a “sale” is not about profit-making but is rather the “first metamorphosis” noted in Capital: moving a product beyond the community boundary to become an item of exchange between subjects that do not belong to the same community.20

Shared passions for socialist-Third Worldist solidarity politics did not neutralize fundamental differences in respective worldviews and policies. Without a common principle and guarantee applying to both, the socialist giver has to convince, explain to, and argue with the Third Worldist recipient as to why the to-be-provided gift is worthy of acceptance. This dimension of selling/buying functioned as the actual mechanism of communication, interaction, and exchange between different political categories, namely the self and the other. In many cases, for instance, Chinese architects in Africa had to put their training in socialist architecture aside and instead learn from the style of tropical modernism that was widespread on the continent at the time, a style with colonial origins and to bourgeois tastes, in order to make their projects acceptable for local authorities.21 Building solidarity in difference was a process full of epistemological interrogations and struggles. Here, the sacrificing subject acted out its promises and consolidated its revolutionary self-portrait while simultaneously challenging that image in its confrontation with a world not captured by its own ideological worldmaking.

Once the subject becomes conscious of itself and others, sacrifice can be a blessed and magnificent thing that transcends everyday life, creating a rare experience of emancipation. If not, however, sacrifice can become painful and meaningless, provoking a vengeful backlash. That backlash happened dramatically in China, with the dissolution of ideas of world revolution, the cessation of China’s leftist radicalism (Maoism), and the powerful onslaught of the capitalist mindset through globalization and Pax Americana. Ever since, sacrificing for others in either the international or the domestic context has become undesirable, if not taboo. And when it does appear, sacrifice is no longer a route to self-fulfillment, but potential proof for claiming for compensation in court. In 1982, the ministerial-level foreign aid agency was abolished and merged into other ministries. While in the mid-1960s more than 600 employees worked on aid in the state-level institution,22 by the late 1990s the institution had become marginal, with only around sixty staff members.23

Despite all of the ruptures over the past half century, Chinese architecture has never left Africa. Among China’s four oldest overseas construction companies today, three originated as Maoist aid organizations.24 Adequate knowledge of working overseas, mature organizational structure, and relevant prior projects gave these organizations a stronger position for acquiring international contracts in the post-Mao, market-oriented transformation that took place starting in 1979. The first contracts came from Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Somalia, and Malta, all of which had prior contact with Chinese aid projects. The focus of these remaining aid programs has largely shifted away from industrial architecture towards more symbolic structures, like stadiums and auditorium halls.25 The red builders for the world revolution became global contractors in the post-Cold-war period.

In 2018, China again set up its independent foreign aid agency, the vice-ministerial China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), plausibly replacing the ministerial-level foreign aid agency that was abolished in 1982. In a recent aid policy document co-issued by CIDCA, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Commerce, one of the primary goals of this aid is “building the Belt and Road Initiative together at a high level.”26 Despite its expectations of a greater global role and its abundant financial and industrial capacity, China’s foreign aid today feels confused and reluctant, and lacks of sense of meaning. China’s post-revolutionary nationalism and economism, while often described as opposed to each other due to different ways of reasoning and class bases, show their intrinsic connectedness in a shared antipathy towards nonreciprocal giving. Neither the Maoist principle of “the poor helping the poor” nor empire’s projects like the Marshall Plan (neither of which cared about monetary repayment, but for different reasons) are popular in China. Through mega projects like the Belt and Road Initiative, however, China hopes to present itself as an apolitical, prudent, and non-discriminating goods supplier who can make the risky capitalist world more sustainable, human, and reliable. This neutralizing tone goes hand-in-hand with China’s ongoing project of self-interpretation by integrating Maoist and post-Maoist political narratives into a single, coherent one.

The past is a foreign country, whether it is loved or hated. The point of retelling this Maoist story is neither to assess the extent to which nonreciprocal giving was able to achieve its goal, nor to morally judge China’s post-Mao shift in aid practices. The point is not even about China, which is just an avatar of human behavior in this context. The point is to find out under what circumstances humans audaciously give and share in spite of the little that they themselves have. The reasons vary and are all specific, of course, but the universality of the giving sprit rises in diverse forms. If there is such a thing as historical progress, it comes from a greater acknowledgement that the repressed history of the human is equivalent to the repressed human in history, which awaits a return at higher levels. The concrete relics I encountered in my fieldwork can therefore be destroyed, but not defeated.

The subsequent seven principles are: (2) in providing aid to other countries, the Chinese government strictly respects the sovereignty of recipient countries, and never attaches any conditions or asks for any privileges; (3) China provides economic aid in the form of interest-free or low-interest loans, and will extend the time limit for repayment when necessary so as to lighten the burden on recipient countries as far as possible; (4) in providing aid to other countries, the purpose of the Chinese government is not to make recipient countries dependent on China but to help them embark, step by step, on the road to self-reliance and independent economic development; (5) the Chinese government does its best to help recipient countries complete projects that require less investment but yield quicker results, so that the latter may increase their income and accumulate capital; (6) the Chinese government provides the best-quality equipment and materials manufactured by China at international market prices, and, if the equipment and materials provided by the Chinese government are not up to the agreed specifications and quality, the Chinese government undertakes to replace them or refund the payment; (7) in giving any particular technical assistance, the Chinese government will see to it that the personnel of the recipient country fully master the technology; and (8) the experts dispatched by China to help in construction in recipient countries will have the same standard of living as the experts of the recipient country. Chinese experts are not allowed to make any special demands or enjoy any special amenities.

Deborah Brautigam, The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 41.

Weizhong Fang, eds., The Chronicle of the Economy of the PRC (1949-1980) (共和国经济大事记)(1949-1980) (Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 1984), 544, translated by the author.

Xiaoyun Li and Wu Jin, “The Practical Experience of China’s Aid to Africa and the Challenge It Faces” (中国对非援助的实践经验与面临的挑战) China Agricultural University Journal (Social Sciences Edition) 26, no. 4 (2009): 45-54, translated by the author.

Quintin Bach, “A Note on Soviet Statistics on Their Economic Aid,” Soviet Studies 37, no. 2 (April 1985): 269-275.

Lin Shi et al., China Today: Economic Cooperation with Foreign Countries (当代中国的对外经济合作) (Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 1989), 140, translated by the author.

This fable appears in multiple texts with slight differences. The earlier earliest sources appeared in the third to the first century B.C. One is《吕氏春秋·贵公》, section “Honoring Impartiality,” in John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, The Annals of Lv Buwei: A Complete Translation and Study (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001), 71; and《说苑·至公》, section “Supreme Impartiality,” Shuo Yuan/Garden of Stories, translated by the author.

Kojin Karatani. The Structure of World History: From Modes of Production to Modes of Exchange (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program (Part 1) (1875). See ➝.

I am grateful to Łukasz Stanek for reminding me of this fact.

For instance, Branko M. Peselj, “Communist Economic Offensive Soviet Foreign Aid—Mans and Effects,” Law & Contemporary Problems 29, no. 4 (1964); Philip Snow, The Star Raft: China’s Encounter with Africa (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988), 145-147.

Rugen Ye et al., The Biography of Fang Yi (方毅传) (Beijing: People’s Press, 2008), 476, translated by the author.

Zhangxi Cheng and Ian Taylor, China’s Aid to Africa: Does Friendship Really Matter? (London: Routledge, 2017), 32.

Shanghai Municipal Archives (No. B32-2-121).

Hong Zhou and Hou Xiong, China’s Foreign Aid: 60 Years in Retrospection (Singapore: Springer, 2017), 79.

Michael Wolfers, Politics in the Organization of African Unity (London: Methven, 1980), 167.

Julius Nyerere. Non-alignment in the 1970s (Opening address given on April 13, 1970 for the Preparatory Meeting of the Non-aligned Countries, Dar es Salaam, April 13–17, 1970), printed by the Government Pinter, National Archives of Tanzania.

Ng’wanza Kamata. Development as Rebellion: A biography of Julius Nyerere (Book II) (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2020), 205.

Institute of International Development Cooperation, Ministry of Commerce, PRC 2020 Report of China and International Development (《中国与国际发展报告2020》以“纪念、传承与创新—中国对外援助70 年与国际发展合作转型), 97, translated by the author.

Karl Marx, “Money, Or the Circulation of Commodities,” in Capital Vol. 1 (1867). See ➝.

Ye Liu, “New China and the New World: Three Lines to Understand China’s Early Architectural Foreign Aid,” in Exporting Chinese Architecture, eds. Charlie Qiuli Xue and Guanghui Ding (Singapore: Springer, 2022), 25–44.

Ye et al., Fang Yi, 268.

Zhou et al., China’s Foreign Aid, 19-20.

China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) is the exception. The other three, namely, China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), China Complete Plant Exportation Company (COMPLANT), and China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) all have predecessors that trace back to 1958, 1959, and 1968, respectively. The predecessor of CCECC, for instance, was the Foreign Aid Office of the Ministry of Railways, which was set up for conducting TAZARA in 1968.

Zhou et al., China’s Foreign Aid, 155.

Administrative Measures for Foreign Aid 《对外援助管理办法》, 2021. See ➝.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.