In December 2021, I found myself making a decision that seemed, at first glance, to run counter to the very core of what my architecture and urban design studio had stood for over the years. I chose to return a grant—a not insignificant sum, exceeding a quarter of a million dollars—to the very philanthropic foundation that had generously offered it. This funding was designated for an effort both modest in scope and profound in ambition: the establishment of a community resource library in Detroit’s historic North End. Aimed at bolstering a well-respected nonprofit running an urban farm, the adaptive reuse project was to act as a spark of hope in a city too frequently characterized by narratives of decay and resilience. Once realized, it was envisioned to be a cornerstone for a broader process of neighborhood regeneration, offering programs and resources that would enable residents to spearhead their own self-directed and durable revival.

Turning down a gift of this magnitude, especially within a context of acute need, was more than just a mere departure from norms. It was a sobering declaration that illuminates the complexities of producing social impact design within communities marred by long-standing neglect, and highlighted the nuanced, occasionally fraught, nexus between philanthropy and the practice of architecture and urban design. It also prompted our studio to think critically about how philanthropy operates within the fabric of community life—its physical environment, social frameworks, governance, and the dynamics of local politics and identity. Thus, this story is as much about a project that never was as it is about ongoing discussions of the role of design in fostering social change, the stewardship of philanthropic resources, and the often challenging, contested paths to positive urban transformation.

There has recently been a profusion of analysis and insightful commentary on American philanthropy. Oliver Zunz has dissected how philanthropy has insinuated itself into the fabric of the nation’s civic and cultural identity, blending altruism with self-interest.1 Meanwhile, David Callahan and Anand Giridharadas each scrutinize the societal impact of philanthropy, arguing that the charitable endeavors of the global elite, rather than mitigating the roots of inequality, may actually entrench existing power structures, sidelining true democratic reform.2 The local interactions with philanthropic activities in urban settings that I have engaged with first-hand, though limited in scope, offer a perspective on the broader dynamics of philanthropic influence on the shaping of communities and the continuous experiment of democracy in America.

Rough Translation

My initial encounter with philanthropy was anything but deliberate. After graduating from architecture school in the shadows of the 2008 financial crisis, I found myself in a field rife with growing inequality and limited opportunities for experimentation. For my fledgling studio Akoaki, a practice I co-founded with my partner Jean Louis Farges, the conventional prospects in our field seemed to be dwindling. In search of more promising opportunities, we cast our sights towards Europe, where the practice of social impact design seemed to be holding together better, buoyed by governmental funds and a political commitment, at least outwardly, to universal, democratic, urban ideals. The work of Patrick Bouchain’s Construire, the collective Exyzt, and Raumlabor stood out as enviable models. Their communal ethos, engagement in participatory design, and cross-disciplinary approach resonated with us. Motivated by their example, we aimed to transplant these practices into a starkly different scenario, that of the American Rust Belt, and of Detroit in particular.

In the “Motor City,” however, the promise of collectivity and democratic resource distribution persistently clashes with reality. Once the heart of the nation’s automotive industry and a symbol of its manufacturing prowess, Detroit has long grappled with the profound challenges wrought by a drastically diminished population, an eroded tax base, and an overwhelming expanse of infrastructure in dire need of care. The local government, stretched thin across a vast urban territory in decline, is ill-equipped to provide the very basics: public education, stable housing, transportation, and access to healthcare for its residents. Compounding all this are the deep-seated racial dynamics that pervade the city. Detroit’s majority Black population has faced systemic barriers to equality, with the racialization of poverty and urban neglect shaping both the city’s internal operations and its relationship with state and federal authorities. A diminished flow of essential resources from higher levels of government has only further entrenched urban disparities.

Philanthropy has thus entered into the void left by the retreat of public stewardship. Propelled by a sense of urgency, it seeks to mend the gaps wrought by abandonment. These endeavors, while praiseworthy in their intent, also illustrate the risks inherent in depending on the benevolence of the wealthy to solve crises that are, fundamentally, failures of the state. In the context of Detroit, philanthropy has ascended from being a mere auxiliary force to become a crucial foundation, positioning itself as the go-to solution for the profound lack of public support in the stewardship of infrastructure, civic endeavors, social initiatives, and the broader spectrum of welfare services. This shift not only absolves the governmental of accountability, but also raises questions about the sustainability and ethics of substituting public duty with private goodwill.

Our pivot to working within these urban realities came suddenly, sparked by a serendipitous encounter in 2012 with a Detroit community organizer who we will call Kylie Rogers. Dynamic and deeply committed to grassroots community engagement, Kylie served as the conduit through which Jean Louis and I were introduced to an ensemble of artists and residents in Detroit’s North End, which we can refer to as the Detroit Street Artists Collective (DSAC). At a crucial but early point of organizational transition, DSAC regularly convened in a partially operational print shop. The gathering place was under the stewardship of a Teamster known for his larger-than-life tales of youthful altercation and savvy political strategy, such as organizing pizza parties and transportation for elderly voters. His building, notable for its intact roof—a rarity in the commercial heart of the neighborhood—stood as a symbol of the community’s grit and determination. Here, the collective’s meetings became more than just planning sessions; they interlaced political discussion with plots to counter the advances of competing nonprofits and reflections on a time when the neighborhood vibrated with the energy of cultural icons like George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, and Aretha Franklin, and was visited by President John F. Kennedy.

Rooted in a predominantly African American neighborhood, where the specter of poverty loomed large and roughly 70% of the buildings lay in ruins or had been demolished, the collective formed a nexus of camaraderie and shared ambition. Their efforts, though nascent, had already yielded tangible results: securing microgrants for block parties and creating murals that both beautified the neighborhood and masked structural decay. In seeking a partnership with our studio, they saw in architectural expertise a means to further narrate and disseminate the cultural essence of their community, aiming to leverage this collaboration into projects of greater scale and impact.

We welcomed the invitation to collaborate with DSAC, as much for its nebulous objectives as for the promise of collective reciprocity. For Jean Louis, with his background as a working-class French expatriate, and for me, a refugee from the Soviet Union, the perils of cultural erasure and the sting of invisibility were not abstract concepts but lived realities. Our personal histories gave us a different perspective on the challenges faced by our collaborators, along with the sensitivity and tools needed to highlight the contextual and cultural significance of a place, even when material resources were scarce.

Over the course of many months, in concert with local residents and students from the University of Michigan, we embarked on what could be termed a form of narrative archaeology. We documented tales of urban decay, charted the disappearance of community landmarks, and mapped the scars left by white flight. Amidst these narratives of loss, we also uncovered vestiges of a vibrant past: an avant-garde fashion scene, underground music venues, and the emancipatory strides of Detroit’s Black middle class. These narratives were gathered and disseminated through catalogs, magazines, and exhibitions intentionally developed to reach a wide audience. Our aim was to strip away the layers of fear and misconception that envelop marginalized neighborhoods. In doing so, we sought to cultivate political dialogue about the pressing need for durable regeneration. To anchor this work within the context of the neighborhood, we transformed an abandoned barber shop into a collective space. Its antique chairs became the setting for casual dialogues and shared recollections. In parallel, contextually significant and aesthetically specific installations throughout the neighborhood magnified the community’s call for transformation.

Barbershop, previously Pancake Party Store, undergoing renovation, North End, Detroit (2014). Photo: Akoaki.

Refurbished barber shop serving as cultural venue and design office, North End, Detroit (2014). Photo credit: © Piper Carter.

Refurbished barbershop serving as cultural venue and design office, North End, Detroit (2015). Photo: Akoaki.

Barbershop, previously Pancake Party Store, undergoing renovation, North End, Detroit (2014). Photo: Akoaki.

Prospects in Hitting Rock Bottom

This work in the North End was taking place against the backdrop of Detroit’s monumental 2013 bankruptcy—the most severe in the history of United States cities, with the city $18 to $20 billion in debt. The city’s liquidation triggered an ambitious campaign of urban revitalization and a concerted effort to reverse its long-standing decline. It was here that we witnessed firsthand the spectacle of home demolitions unfolding with a cadence and regularity that bordered on the ceremonial, marking an attempt by the city to purge itself of accumulated decay. Day after day, the ruins of countless homes were carted away, destined for landfills, in a process underwritten by federal dollars from the Obama administration and private equity.

The relentless barrage of media attention that accompanied this bulldozing marred the cityscape, branding it variously as “unfinished,” “underdeveloped,” or an “economic anomaly.” It summoned the very dichotomies that Ivan Illich had worked to dismantle almost a half century earlier in his critical discussion of the problem of charity in America.3 For Illich, the harsh distinctions between what was termed the developed and underdeveloped worlds revealed the West’s aid to its southern neighbors to be not an act of benevolence but a tool of condescension and modernity, aimed at remolding the world to mirror its own ideals.4 In Detroit, this confrontation with underdevelopment was brought home, coupled with the epiphany that modernity itself could stumble, even on North American soil. Under the glare of mediatized scrutiny, these revelations following the city’s bankruptcy ignited a wave of giving, pushing the limits of goodwill to new heights.

To outsiders, Detroit’s disarray has long been not just a landscape in need of aid, but a site of high-minded altruism, of the kind that John F. Kennedy championed in his call to “noble action” when he addressed members of Congress and the Diplomatic Corps of the Latin American Republics in 1961.5 Locally, Detroit became a charitable rallying cry with private philanthropies waging battle against the city’s expansive infrastructural and social challenges. Between 2007 and 2011, benefactors injected over $620 million into Detroit, aiming to ease harsh realities for families in need. In 2014, a consortium of fifteen foundations, from both within and beyond the city, and joined by corporate and individual givers, committed $466 million to bolster the city’s failing pension system and to transition the Detroit Institute of Arts to nonprofit stewardship. This philanthropic intervention was crucial to the crafting of a grand bargain—a mix of concessions, cuts, and contributions—that ultimately safeguarded the Detroit Institute of Arts’ venerable collections, ensuring their preservation against the threat of liquidation.6

During this period, our collaboration with DSAC allowed us to navigate minor grants, securing resources for small capital enhancements, diverse cultural programming, and local job creation. The scene shifted significantly, however, with the arrival of ArtPlace America, a philanthropic consortium that stood out from the more embedded, calibrated efforts of local philanthropy. ArtPlace represented a formidable national alliance: a $150 million venture spanning from 2010 to 2020, backed by an array of foundations (including the Barr Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, The Ford Foundation, The James Irvine Foundation, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The McKnight Foundation, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, William Penn Foundation, The Rockefeller Foundation, Rasmuson Foundation, and The Surdna Foundation, along with two anonymous contributors), federal bodies, and financial institutions. It was driven by a lofty goal: to integrate art and culture—mostly in the form of creative placemaking—into the core of community planning and development. Yet, faced with the task of disbursing a significant budget within a tight timeframe, ArtPlace’s approach effectively morphed into a rapid urban experiment, prioritizing immediate action over the lasting impact and sustainability of its projects.

Experiments in Giving

ArtPlace grants landed with a sense of immediacy and force that was at once invigorating and daunting—sums of $150,000, $300,000, $500,000, each promising significant change and trackable outcomes. Grants were dispensed in eighteen-month cycles, creating a rhythm of expectation and delivery. Through this process, ArtPlace established itself not just as a benefactor, but also as a dynamic research institution dedicated to setting agendas, learning through action, organizing symposiums, and producing public scholarship.

Within the ambit of ArtPlace, artists were positioned not as peripheral contributors but as pivotal agents, working in close concert with urban planners, developers, and government officials to forge and execute innovative solutions to a broad spectrum of community issues. With great optimism, ArtPlace envisioned a synergistic confluence of efforts from community developers, cultural institutions, academia, and philanthropic organizations, all mobilized to champion its approach. The arts and culture sector, designated as essential to the fabric of community planning and development, would offer a wellspring of expertise and creativity poised to drive better outcomes for communities. In the meantime, funded projects would serve as critical sources of data for honing effective methods of equitable regeneration.

In both theory and practice, ArtPlace embraced a sweeping and influential strategy, casting a wide net across sectors as varied as agriculture and food, youth development, environmental and energy issues, health, housing, and more. Under the guidance of ArtPlace’s dedicated program officers and directors, projects were carefully steered into one of these diverse areas of impact and strategically aligned with the organization’s overarching goals.

Some projects seemed a perfect fit for this framework. Take, for example, the Detroit Street Urban Farm (DSUF), a community-focused urban farming initiative we collaborated with for six years. Before ArtPlace’s involvement, we had already been integrating the arts into DSUF’s agricultural and food production efforts. In fact, the fusion of art and performance with a productive landscape didn’t just make conceptual sense; it became a lifeline for a venture that couldn’t rely on farming alone to cover its annual financial needs. With micro-grants from local charitable organizations, we had constructed opera sets for experimental happenings amid vegetable plots, and merged music with jam-making festivals. ArtPlace support promised to strengthen the foundations of this agri-cultural project already in progress.

Meanwhile, other community works underway, such as a music venue dedicated to preserving cultural heritage and fostering new genres through experimental collaboration, were encouraged by ArtPlace to expand their missions—by exploring, for example, how such a music venue could expand the provision of mental health services to Black neighborhood youth. While funded, this project ultimately failed due to its members inability to structure a governing entity, let alone serve as a hub for mental health assessment or services. Despite these clear challenges, ArtPlace’s conviction in art’s transformative capacity to elevate communities and propel regeneration never wavered. This steadfast belief endured, even in the face of programmatic dissonance or a lack of expertise among participants.

There were notable, albeit anecdotal, outcomes to such open-handed and expansive philanthropy. For instance, casting the arts as the foundation of urban renewal led to an undeniable surge in individuals identifying as artists. With average household incomes in the North End hovering around $35,000 at the time, the allure of the arts became pronounced, particularly as philanthropic initiatives dispensed grants in the hundreds of thousands of dollars to organizations eager to get in line.

ArtPlace funded both for-profit and nonprofit entities, regardless of their proven stability, organizational structures, or established operating frameworks. This resulted in groups, often only loosely affiliated and/or in a state of formation, like the Detroit Street Artists Collective, having to grapple with the responsibility of managing gifted funds. Fiscal sponsorship served as a temporary solution for holding these resources, but it also set the stage for internal strife, as affiliates clashed over control, authority, and the direction of resource allocation. Moreover, the method of disbursing these funds—sometimes dramatically unveiled during public meetings or mailed through the postal service in the form of single checks—fostered competition and envy among partners, residents, and other stakeholders. The hurried nature of this process inflicted its own brand of harm, introducing inequities as it sought to distribute resources within the community.

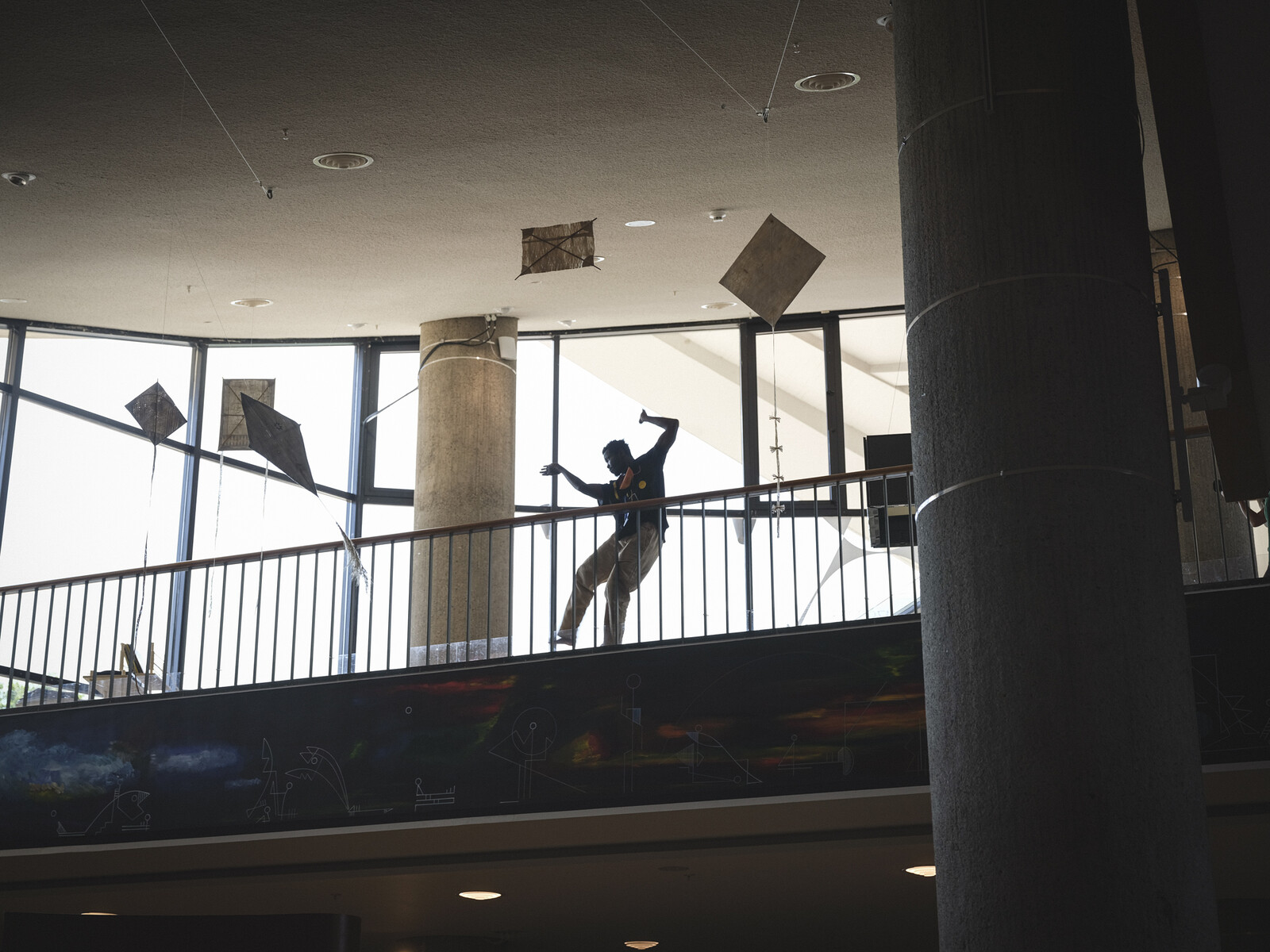

Preparation for an architectural installation, North End, Detroit (2016). Photo: Akoaki.

Ephemeral Culture Council Arch installation, North End, Detroit (2016). Photo: Akoaki.

Art installation by Efe Bes at former grocery store, North End, Detroit (2017). Photo: Akoaki.

Preparation for an architectural installation, North End, Detroit (2016). Photo: Akoaki.

Tactical Opportunism

The air at the Detroit Street Urban Farm was charged with anticipation as the arrival of Luis Rivera and Marisol Hernández, respectively the ArtPlace program director and lead project coordinator, loomed on the horizon. Their presence marked a pivotal moment—an evaluation of our collective labor to date: the installations we had constructed, the publications on water management we had authored, and the community and economic sustainability models we had developed in concert with experts across a range of fields. Yet, their presence was not merely to audit achievements already brought to fruition. It was also about looking ahead, motivated by a new funding application we had put forward. Born out of relentless effort and quiet perseverance, the proposal aimed to design a six-acre guiding plan and breathe life into dormant structures on the farm. It was a vision that had been slowly pieced together with the help of moral investors and local residents, by acquiring land through the Detroit Land Bank auction and donating it to the nonprofit farm and effectively transforming it into one of the largest property holders in the area. Now, the prospect of a first ArtPlace grant promised to usher in an ambitious new phase of capital improvements for the farm.

In a display of broad-based support, the urban farm rallied a varied crowd: residents, musicians, artists, staff, and children from after-school programs, together embodying the community’s diversity and the dynamic energy essential for the project’s success. On this perfect summer day in 2016, this collective warmly embraced Luis and Marisol. Amidst the backdrop of jam-making in the community house and children’s laughter in the kale patches, the group envisioned a future rooted in community leadership, collective effort, and utopian aspiration. The sincere enthusiasm and unified commitment visibly impressed Luis and Marisol. During a conversation around a freshly painted picnic table, they not only offered feedback and guidance, but also challenged the project’s modest funding request of $350,000, urging the farm’s directors to raise their sights to the ArtPlace grant ceiling of a half million dollars. They assured those gathered that the necessary funds would be secured promptly, affirming their confidence in the project’s vision and the community’s ability to bring it to fruition.

The swift bestowal of a $500,000 grant to the farm following Luis and Marisol’s visit, within a community where such quantities of money seemed nearly mythical, raised questions. Given a significant influx of capital, not allocated by a democratically chosen entity but by an independent organization with the power to influence both local and broader institutional dynamics, how could the fair distribution of resources be assured? Which programs would benefit first or most? What would the decision-making process look like? Local opportunists, drawn by the promise of easy money, began to circle, demanding exorbitant fees for mediocre or unnecessary services. The caretakers of the farm, fully cognizant of their vulnerable position and the need to sidestep claims of favoritism, often relented. Consequently, the grant dissipated quickly, with the ambitious objectives it aimed to achieve left in the dust.

After securing an ArtPlace grant, the Detroit Street Urban Farm became a magnet for a procession of donors masquerading as partners. The CEO of DTE Energy, flanked by a brigade of employees donning branded volunteer t-shirts and surrounded by security, dramatically arrived at the farm to present a plastic tool shed. A sports team donated equipment for youth programs, which meant the farm had to build a storage unit. Next, a Belgian artist arrived with an ambitious vision: to introduce crossbred chickens from around the globe as food sources in impoverished communities through his Social Impact Chicken project. This international art initiative, launched in 2016 and previously prototyped in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, quickly took tangible form. The chickens were settled in a coop next to a foreclosed home. Collaborating with a notable gallery in Detroit’s Eastern Market, the project quickly garnered recognition from the New York Times.

Initially propelled by missions of autonomy and sustainability, numerous nonprofits and community groups like the Detroit Street Urban Farm found themselves ensnared in a cycle of dependency, reliant on a continual stream of grant funding for survival. This reliance redirected their focus from strategic, community-centric planning towards a tactical opportunism, with an eye more on immediate outcomes than structural durability. Furthermore, the influx of substantial grants not only compelled but also normalized an incessant quest for organizational growth and fiscal security, measured by increases in staffing and spending. The pursuit of further funding evolved from a judicious choice to an urgent necessity, drawing in corporate sponsors and creative contributors to the urban tableau. In such an environment, traditional planning became a quixotic endeavor, overtaken by the whims of episodic interventions and the unpredictable flow of “gifts.” The result is a landscape where outcomes are not the product of systematic effort, but rather the accumulation of sporadic acts and opportunities, each seeking the mediatized glow of benevolent recognition and leaving its own imprint on the urban fabric.

Decoy Gifts

Our initial engagement in Detroit hinged on a belief in philanthropy as a reciprocal agreement, with support tethered to specific outcomes outlined in grant proposals and contracts. We envisioned our work more as barter than as an acceptance of gifts, in which the means and ends were laid bare, fostering transparency around everyone’s motivations and objectives. Yet, over time, this balance of exchange, and the realization of commitments attached to donations, grew elusive, entangled in cultural conflicts, power plays, and ethical contradictions, breeding dependency and strife not only in the community, but also in the collective we imagined ourselves building with our partners.

Over the span of our studio’s decade-long chapter in Detroit, we have witnessed many philanthropic organizations, previously anchored by a commitment to measurable impacts, gradually shifting towards more obscured, unilateral forms of support, and, at times, sidestepping procedural hurdles altogether. This transition towards what could best be described as ad-hoc restitution, rather than a deliberate blueprint for reconstruction, effectively bypasses the vital, albeit messy, processes of democratic participation and conflict resolution. In this scenario, our repeated efforts to secure funding for persistently unrealized projects cast us, perhaps inadvertently, into the role of benefactors. We found ourselves ensnared in a cycle of providing rather than partnering, a dynamic that distanced us from the collaborative pursuit of shared objectives.

Our growing sense of disenchantment stemmed not solely from the relentless cycle of applications, or our collective’s habitual incapacity to honor its commitments. It was precipitated by the realization that, in a system where architects are regarded not as indispensable allies but as fleeting benefactors and replaceable parts, the overarching vision that underpins a project becomes secondary to the routine activities of the community organization. Thus, when we opted to return the allocated funds for the establishment of a community resource library, our decision was met without resistance and our concerns over the surging costs of construction—further inflated by pandemic-related delays—were essentially ignored. Upon surrendering the funds, the foundation redirected them with notable efficiency to an alternate team of designers and their affiliated university. Constrained by the budget or driven by a different set of priorities, this group managed to get to the ribbon cutting but resorted to materials such as vinyl siding—undoubtedly practical, though fundamentally at variance with the original intention of promoting environmental sustainability and addressing the challenges of climate change.

The deep flaw in philanthropy is not the caliber of the outcomes it endorses. The issue is philanthropy’s marked preference for steering community endeavors towards projects that are both intensely localized and modest in ambition. These projects, while undeniably beneficial, carry the inherent danger of shifting focus away from the vast, systemic challenges that loom large over the city. This granular concentration can act as a smokescreen, obscuring the urgent need for broad, collective efforts vital for addressing the city’s deep-seated issues. Hence, even as philanthropy backs initiatives demanding significant community involvement—deciding, for instance, where to create a mural or how to arrange rain barrels—it inadvertently detracts from and circumvents investment in more pressing concerns. As a result, while communities strive to enhance their individual capacities, the currents of traditional development carry on, directing capital primarily towards Detroit’s urban center, an area dominated by a select few corporate behemoths.

Detroit’s widely celebrated narrative of a grassroots, philanthropy-driven renaissance continues to unfold. However, for all its acclaim, this story subtly undermines the very pillars of public engagement and the spirit of community solidarity upon which it claims to stand, and highlights a disconcerting drift away from the inclusive dialogue and action that are crucial for a truly equitable and sustainable urban revival.

Oliver Zunz, Philanthropy in America: A History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

David Callahan, The Givers: Wealth, Power, and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017); Anand Giridharadas, Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018).

Ivan Illich, The Church, Change and Development (New York: Herder and Herder, 1970).

Illich, The Church, Change, and Development, 30, 38–49.

John. F. Kennedy, “Address at a White House Reception For Members of Congress and for the Diplomatic Corps of the Latin American Republics,” March 13, 1961. See ➝.

“Keeping the Lights on in Detroit,” Philanthropy Roundtable, 2014. See ➝.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.

Category

Subject

The identities of all collaborators and their organizations mentioned in this article have been anonymized.