Plugged In to the Community

In order to explain the influence of technology in East Palo Alto, California, it is best to start by examining the historical convergence of political and philanthropic ideologies at the precipice of the dot-com bubble. In his initial bid for the United States presidency in 1992, Bill Clinton vowed to “end welfare as we know it.” Holding true to his word, on April 18, 2000, then-President Clinton enacted a plan to ameliorate the “digital divide” of the 1990s and help young people “Get Connected” with a “public–private” initiative that provided over $2 billion in tax incentives to improve technology access in disinvested communities.1 Webcast live by Hewlett Packard (HP), President Clinton lauded the partnership between the East Palo Alto nonprofit Plugged In and the computer manufacturer HP as an example of how corporations and the community can work together.2 Within a low-income city such as East Palo Alto, which had been left behind in the technology revolution that enriched the rest of Silicon Valley, the event was commended for its collaboration between local leaders and corporate “angel investors,” and as a way to mitigate the issues that had been burdening the community for over twenty years.3

During the webcast, the largest techno-corporate donor and host of the media-headlining event, HP, pledged to spend $5 million on a new building for the Plugged In community computer center.4 According to HP, the company selected the city of East Palo Alto because of its proximity to the company’s headquarters. “We’ve had a long-standing relationship with East Palo Alto, and it made sense to begin bridging the digital divide that existed in our own backyard.”5 Carly Fiorina, the CEO of HP at the time, further announced that East Palo Alto would be one of three sites for their Digital Village program, to which they would be donating $15 million in HP products, services, and education over three years, with $1 million going towards the expansion of the Plugged In computer center.

As he stood on stage, surrounded by Silicon Valley leaders and CEOs, Clinton articulated one of the most defining statements for the trajectory of philanthropic redevelopment in the city of East Palo Alto: “We can use new technology to extend opportunity to more Americans than ever before, we can truly move more people out of poverty more rapidly than ever before; or, we can allow access to new technology to heighten economic inequality and sharpen social division.”6 The event was celebrated for “fighting poverty with tech,” a quixotic endorsement of the power of the internet before the burst of the dot-com bubble.7

This public–private initiative brought together community leaders, political forces, and Silicon Valley largesse at the turn of the twenty-first century and prefigured the “philanthrocapitalism” that has taken place in East Palo Alto in the twenty years since.8 Given its external perception as an island of poverty within a rising sea of wealth, East Palo Alto has been the focus of evermore frequent acts of paternalistic outreach from its Silicon Valley neighbors, each attempting to ameliorate the inequities resulting from the success of the city’s benefactors.

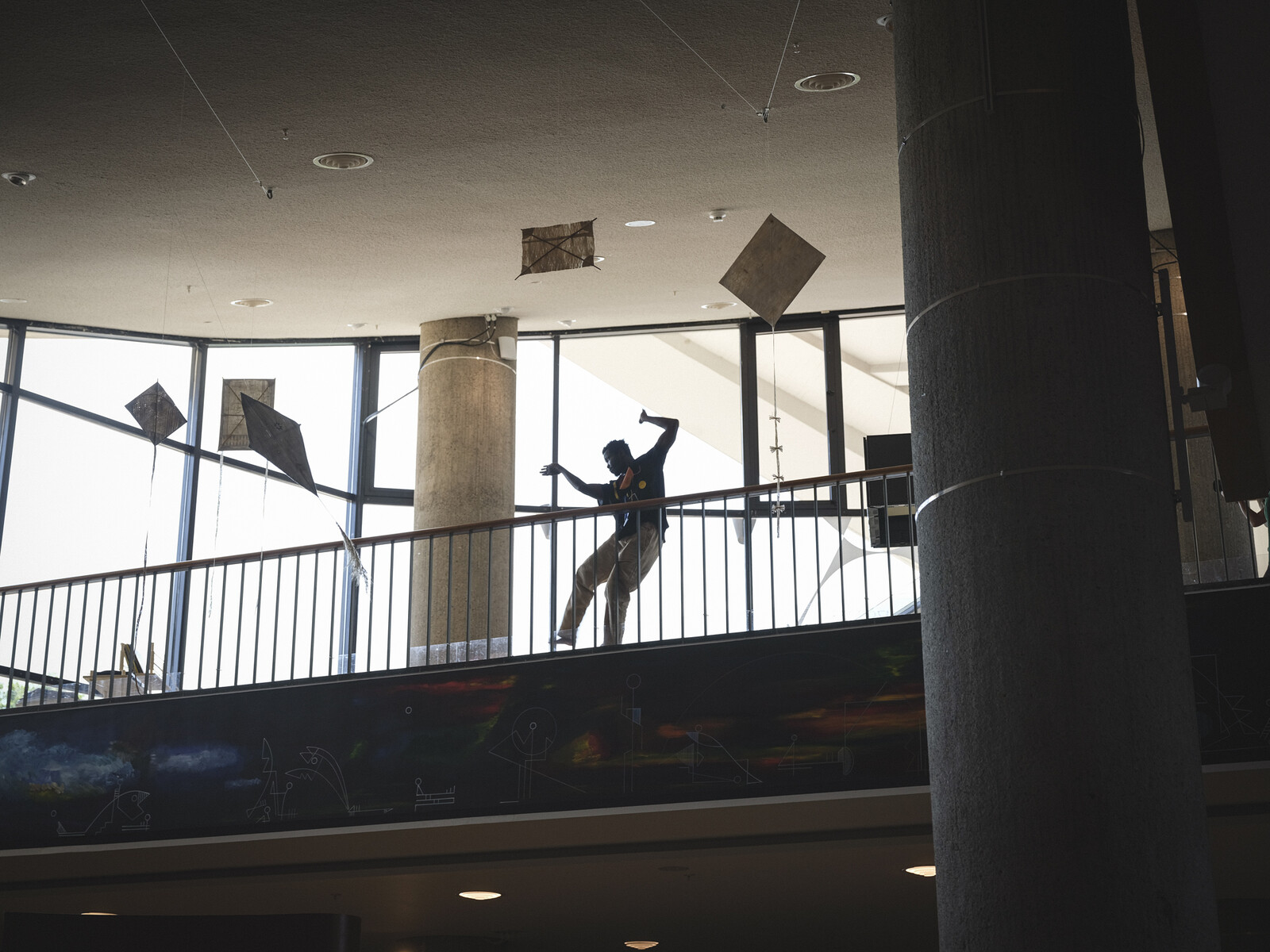

The Emerson Collective, in collaboration with BIG Studio, James Corner Field Operations, and Arup Architects organized two years of community-led design workshops. Source: Project Bloomhouse.

East Palo Alto’s History of Redevelopment

Despite its location within one of the wealthiest counties in the United States, East Palo Alto, a city whose 30,000 residents are predominantly Latino, African American, and Pacific Islander, has a poverty rate higher than the national average.9 The history of East Palo Alto is representative of many cities that have struggled with a history of disinvestment, displacement, and dirty development. The implementation of redlining and blockbusting practices throughout California in the 1950s led to many of the demographic and socioeconomic differences that exist today between East Palo Alto and its more affluent neighbor, Palo Alto.10 This socioeconomic chasm widened in 1964 when state and federal funding expanded the historic Bayshore Freeway, further intensifying the racial barriers between the affluent middle-class neighborhoods of Palo Alto and the more disadvantaged neighborhoods in the then-unincorporated East Palo Alto, at the time known as Ravenswood.11 Consequently, Whiskey Gulch, East Palo Alto’s closest approximation of a commercial district, was cut off from the easternmost portion of the community and from the rest of the Bay Area.

As the postwar manufacturing boom took off throughout California, East Palo Alto’s need for tax revenue resulted in agreements to take on much of the “dirty development” necessitated by the region’s expansion. This included the county dump, the Romic Environmental Technologies hazardous waste recycling facility—which processed and recycled industrial waste such as solvents, inks, acids and other hazardous chemicals involved in the production of computer parts—and other polluting industries, such Rhone-Poulenc, Inc.—which manufactured pesticides containing arsenic. This development has ultimately led to contamination and pollution that has affected generations of residents throughout the city.12

While the majority-black community fought for incorporation throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the City of East Palo Alto did not receive official recognition until 1983, and only gained official state and federal approval in 1997.13 During that time, residents of East Palo Alto sought acceptance and assistance from their more affluent neighbors in Palo Alto, home to Stanford University as well as Menlo Park, a growing center for many of Silicon Valley’s venture capital businesses. Yet the tail-end of a severe recession, low tax revenue, the destruction wrought by the crack epidemic, and the de-institutionalization of mental health facilities further exacerbated the social and economic strife taxing the already-struggling city.14

In the late 1990s, the financial success preceding the dot-com bubble in Silicon Valley drew attention to the institutionally abandoned East Palo Alto, which, as a result of the socio-political barriers that beleaguered the city, risked becoming another casualty of “fourth-world” urban decline.15 Through efforts to avoid complete underdevelopment, the nascent city council and city redevelopment agency took on two massive commercial projects: the University Circle Project in 1988 and the Gateway 101 Project in 1993. The redevelopment of University Circle and construction of a new Four Seasons hotel were lauded as a commercial and financial success, attracting big box stores such as Home Depot, Best Buy, and IKEA.16 However, they also resulted in the demolition of the historic Whiskey Gulch and its surrounding neighborhood, including over a hundred affordable housing units and twelve local nonprofits, one of which was the Plugged In community center.17 These redevelopment projects brought economic opportunities to the city by way of new jobs, increased tax revenue, and new places of commerce, but also brought rising house prices to a community where over eighteen percent of residents lived below the poverty line.18

Many of the successful development projects implemented throughout East Palo Alto were thanks to the assistance of the city’s Redevelopment Agency, a publicly funded body that provided local governments in California with tools to address urban problems such as blight and a lack of affordable housing. Initiated in the 1950s, California’s redevelopment agencies assisted local governments by developing plans and providing the initial funding to encourage and attract private investment—investment that would have been difficult for municipal governments to obtain on their own. The City of East Palo Alto Redevelopment Agency assisted in the implementation of both the University Circle Project Area and Gateway 101 Project Area, both of which were considered accomplishments within the small city’s government. The Redevelopment Agency also provided a proposal for the redevelopment of the Ravenswood Project Area, encompassing the Ravenswood Business District, an area currently undergoing development. However, when the State of California dissolved all local redevelopment agencies in 2012, East Palo Alto was left with a gap in funding and a decreased ability to secure public–private partnerships. This vacuum ultimately allowed new forms of development to emerge, such as the philanthropic interventions leading the city’s current urbanization.

As public–private development has expanded in East Palo Alto, several external organizations have provided philanthropic funding for spaces beneficial to the city’s growth. In 2015, the Ravenswood Family Health Center–Sobrato Campus, a 38,000 square foot health facility, was constructed with philanthropic donations from the Sobrato Foundation and a $5 million contribution from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.19 In 2016, after over a decade of community collaboration with researchers from Stanford University’s John W. Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities, construction began on the 25,000 square foot EPACenter Community Arts & Youth Development Center. Designed by wHY Architects and Hood Design Studio, the EPACenter opened to the community in April of 2022.20 In December of that same year, the Sand Hill Properties Foundation made the “largest donation in Ravenswood’s history,” $30 billion to develop a community hub adjacent to Cesar Chavez Middle School on Bay Road.21 An additional $3 million was donated through the Magical Bridge Foundation partnership between the Peery, Sobrato, and Acton family foundations, the Emerson Collective, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and the Ravenswood Education Foundation. Such philanthropic developments have provided significant benefits for the historically disenfranchised city but have also perpetuated urban inequities. The same economic forces that disenfranchise the city—such as real estate speculation and technocapitalist development—are also what allow its benefactors to achieve success.

While the small city of East Palo Alto is land-rich—land being a highly sought-after resource within the competitive real estate market of Silicon Valley—it lacks the ability to implement much of the infrastructural redevelopment necessary to administer new projects. Ultimately, this means that the technocapitalist gentry of Silicon Valley, by virtue of their philanthropic efforts, can exert significant influence on the city’s urban policies, further displacing its citizens.

Philanthrocapitalism has been slowly shaping urban development in the United States since the late 1990s, a period that has been referred to as a “golden age of philanthropy.”22 As wealth creation has surpassed that of even the Gilded Age, charitable donations throughout the world have increased exponentially. This increase in super-philanthropy (charitable donations by the super-wealthy) has paralleled the past forty years of privatization by the US government, in which funding for social services has precipitously declined under neoliberal and market-driven policies.23 Philanthrocapitalism brings together elements of angel investing, social responsibility, and social entrepreneurship, all mirroring “the way that business is done in the for-profit capitalist world.”24 However, philanthrocapitalist endeavors transfer public influence and control from under-funded civic institutions to the whims of the presumably-benevolent wealthy. Two of the largest forces of philanthrocapitalism in East Palo Alto, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Emerson Collective, are evidence of this, implementing projects that have turned the city into a Silicon Valley incubator for disruptive philanthropy.

The Primary School and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

Within a year of Facebook launching its public IPO in 2012, Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, pediatrician Priscilla Chan, founded the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, a collection of for-profit and nonprofit holding companies under an umbrella organization hailed as “a new kind of philanthropic organization focused on advancing human potential and promoting equality.”25

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) is not a standard nonprofit philanthropic organization, but rather one managed under the business strategies of a limited liability company. While Zuckerberg states that this type of structure gives the organization the “flexibility to execute [their] mission more effectively,” it also means the organization lacks the transparency of traditional nonprofits and minimizes the amount of wealth taxed on the Facebook billionaire’s profit shares.26

One of CZI’s first “initiatives” was The Primary School, a tuition-free private school conceived and co-founded with education specialist Meredith Liu to “provide support that children needed to stay healthy and thrive in the classroom.”27 Their flagship property was launched in East Palo Alto “to have more freedom to design new programs and invest more heavily in areas that are too often casualties of the underfunded public education system.”28 Many community members within East Palo Alto at the time, however, argued that the funding should instead go towards assisting the existing local public schools and its homeless student population.29 Ofelia Bello, then a member of the East Palo Alto Planning Commission, expressed both her enthusiasm and concern regarding the school, “I’m thrilled that our children will be getting a world-class education locally at what looks to be a world-class facility. But I am disheartened at our disinvestment of Ravenswood.”30

While The Primary School states that they are not a charter school, they have received funding from local, state, and federal programs to help subsidize the school’s full-day preschool program and nutritious meals program.31 The school opened in 2016, operating out of the Ravenswood Child Development Center, which is in East Palo Alto’s Ravenswood City School District, one of the lowest performing districts in California.32 In June 2017, The Primary School and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative bought a 3.5 acre site at 1200 Weeks Street, a few blocks down the street from the original school, with plans to build a new three-story building, which would allow the school to double its student enrollment from 250 to 500 students. However, they were unable to move forward with construction due to inadequate funding for access to the city’s sewage system and concerns regarding soil contamination from the nearby Rhone-Poulenc Superfund site.33 Further contention arose when, in November of that year, East Palo Alto city officials enforced the removal of approximately fifty “working homeless” residents living in RVs and other parked vehicles near the site of the proposed school.34

In 2020, The Primary School was able to resolve its desire for a new school space by renting out the defunct Brentwood Academy on Clarke Avenue, around the corner from the Ravenswood Child Development Center, leasing the space for over $1 million per year. The Ravenswood City School District had shuttered the school, along with the Menlo Park Willow Oaks school, in January of that year due to the district’s $1.35 million deficit.35 The current Brentwood Academy location is less than three miles from the Facebook/Meta Corporate headquarters in neighboring Menlo Park.

The Primary School has maintained a positive presence in the East Palo Alto community, providing food assistance to families of students as well as organizing drives for clothing and school supplies. However, sources within The Primary School have intimated that the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative may be pulling out of the community. Forty-eight members of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s Education Team were reportedly laid off in August 2023 “as part of a restructuring of its efforts surrounding philanthropic grantmaking and funding of technology development.”36 Just recently, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative announced a shift towards “science-focused philanthropy.”37

The Primary School’s website states their long-term goal “is to build a game-changing, replicable, and sustainable school model: one that can be shared either whole-cloth or piecemeal with different communities and lead to similarly positive outcomes for children most impacted by systemic poverty and racism.38 However, the Silicon Valley phenomenon of “dogfooding,” or the practice in which tech workers use their own product consistently to see how well it works and where improvements can be made, combined with Zuckerberg’s educational track record in school systems in Newark, Brooklyn, Connecticut, Kansas, and elsewhere, signify larger implications of the way that The Primary School is being implemented within a community that has come to rely on it.39

Bloomhouse, Emerson Collective, and the East Palo Alto Waterfront Development

Just down the street from the city’s most successful revitalization project, Cooley Landing, and a few blocks from The Primary School, sit several unassuming warehouses, interconnected beneath a large, steel truss awning. The space is highlighted by a brightly painted mural, an inspirational rendition of a child representing the East Palo Alto community, looking out over a large, barren field. An undulating fence structure denotes the site as the “community event space” known as Bloomhouse.

Opened in November of 2019, Bloomhouse was ostensibly established to “ensure

[the Emerson Collective] was rooted in the community and able to connect everyday with residents, city staff and leaders.”40 Bloomhouse has even appointed several East Palo Alto community leaders and long-time residents to its board, including the President of the Ravenswood City School District Board of Trustees, Mele K. Latu. However it is Laurene Powell Jobs, known as one of the “most famous women in business,” who is the unassuming figurehead of the Emerson Collective.41

A graduate of Stanford Graduate School of Business, Laurene Powell married Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple, in 1991. When the Silicon Valley tech billionaire passed away in 2011, Laurene inherited her husband’s shares in Apple and the Walt Disney Company, valued at almost ten billion dollars. Her limited public profile and media representation, including only a few well-managed interviews, paint the billionaire philanthropist as a visionary with humble beginnings, aspiring to assist communities with the positive change “necessary” for successful social impact, all enacted through her “impact investment” vehicle, the Emerson Collective.

The position Laurene Powell Jobs holds within the East Palo Alto community extends back to 1997, when she co-founded the nonprofit College Track after “realizing that many of the East Palo Alto children had no idea about how to apply to or prepare for college.”42 This foray into education is frequently cited as the reason why she started the Emerson Collective in 2004. Powell Jobs is often quoted as saying that her experiences working with the students of College Track allowed her to better understand how “complex and entangled the problems affecting disadvantaged communities are.”43

Like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Emerson Collective is also a limited liability company, which allows the tax reporting requirements placed upon more traditional nonprofit structures to be avoided. However, Powell Jobs argues that the unusual structuring of the Emerson Collective allows the philanthropic foundation to circumvent the usual grantor-grantee power imbalance, “investing in innovative solutions that address inequities at their roots.”44

The Emerson Collective describes itself as “a social impact organization, not a commercial developer.”45 That may be because all of its real estate acquisitions have been made through its subsidiary, Sycamore Real Estate Investment. Incorporated in 2014, Sycamore acquired fifty-two acres of land in East Palo Alto between 2015 and 2018, making the Emerson Collective the city’s third largest private landowner.46 In its 2021 application to the East Palo Alto City Planning Commission, a site within the Ravenswood Business District was demarcated as the East Palo Alto Waterfront, a mixed-use development that would include the construction of approximately 1.3 million square feet of research and office space, 50,000 square feet of retail space, and 260 “attainable” homes.47

The Parcel Plan for the proposed East Palo Alto Waterfront Development Project, denoting the extents and acquisition of each parcel as it was acquired by the real estate investment arm of the Emerson Collective. Source: East Palo Alto Waterfront Development Application, Emerson Collective Parcel Plan, 2021.

The post-industrial site proposed for the Emerson Collective’s East Palo Alto Waterfront Ravenswood Redevelopment Project. Photo: Leigh House, 2023.

A rendering depicting the 100,000 sqare foot JobTrain Center for Economic Mobility, designed by William McDonough + Partners. Source: William McDonough + Partners, 2024.

The Parcel Plan for the proposed East Palo Alto Waterfront Development Project, denoting the extents and acquisition of each parcel as it was acquired by the real estate investment arm of the Emerson Collective. Source: East Palo Alto Waterfront Development Application, Emerson Collective Parcel Plan, 2021.

In the East Palo Alto Waterfront Area Plan Vision, the Emerson Collective and its development partners, Peninsula Conflict Resolution Center, Bjarke Ingels Group, and James Corner Field Operations, have proposed a mixed-use, multi-phased development project adjacent to the Ravenswood Wetlands Preserve. The proposal is incredibly detailed, with soft-focused renderings featuring joyful multi-cultural groupings and rhetoric that assures readers that the Waterfront Project is, above all, an opportunity for the community “to bloom.”48

Building off of the city’s 2013 Specific Plan to increase job training within the Ravenswood Business District, Phase 1 of the Waterfront Project will be the construction of a four-story, 100,000 square foot office building for the Emerson Collective’s administrative offices and the career training nonprofit JobTrain. The building site, with a proposed opening date of 2024, will feature a second building, for the Ravenswood Family Health Center, and an underground parking garage that will be shared by the East Palo Alto Waterfront Development offices.49 The development has been implemented through a partnership with Sobrato Philanthropies as an extension of their network of community health centers throughout East Palo Alto.

The Emerson Collective and its venture Bloomhouse celebrate the fact that the “Waterfront [Project] is grounded in a history of working with the community and a long-term commitment to its future.”50 This is purportedly visible in the way the Development Proposal is structured: “co-creation with the community” is cited throughout the Waterfront Area Plan Vision document as the first guiding principle. The principle of community-led design is further emphasized by the inclusion of survey boards from community engagement meetings and photographs of the development team’s early-2020 community conversations that were hosted at Bloomhouse. However, while mixed-use development and the inclusion of housing is outlined within the proposal, the post-industrial area is not zoned for housing, and conversations with Bloomhouse representatives have shown that expanded housing opportunities may not be a part of the planned development moving forward.51

This disclosure comes as the community of East Palo Alto struggles with the planning fatigue that often accompanies such idealistic development proposals. While the Emerson Collective implemented its development plan through community-led design strategies, one could argue that the Waterfront Development Project is dependent not only on the acquisition of the city’s land resources, but also on the extraction and commodification of the community’s creative labor.52

Much like the “philanthrolocalism” espoused by nonprofit specialist Jeremy Beer, Bloomhouse’s strategy of community embeddedness allows for face-to-face encounters with the residents of East Palo Alto.53 The Emerson Collective has tried to further strengthen its ties to the city through the funding of creative endeavors such as the East Palo Alto Community Archive.54 However, such projects have created conflicts for local artists speaking out against the organization, and the community archive will soon separate from the Emerson Collective as a self-managed and self-funded operation.

As such, the peculiar nature of Bloomhouse and its position within the community is uncannily reminiscent of spatial astroturfing, or political activity designed to appear unsolicited and rooted in a local community without actually being connected to it. Many of Bloomhouse’s community events function as little more than public relations tools to garner support for redevelopment. Bloomhouse has forced its way into the community as the primary space of community activity, public engagement, and even planning for the future of East Palo Alto.

The effectively altruistic approach taken by Laurene Powell Jobs may be a more “philanthrolocal” form of development than others in the Ravenswood Business District, but that overlooks the fact that the Emerson Collective and its venture investors stand to profit from the speculative real estate development along East Palo Alto’s waterfront. Ofelia Bello, who currently serves as the Executive Director at the East Palo Alto nonprofit, Youth United for Community Action (YUCA), shares this concern:

Bloomhouse to me is reminiscent of this trend I’m seeing among philanthropists in our immediate region that have two arms: one which does philanthropy-[like] social good, issues grants, supports oftentimes important work that’s happening in our community. And then with the other arm they do real estate development and stand to gain considerable profit.55

On its surface, the philanthropic development of the East Palo Alto Waterfront Project seems like a good thing for the overlooked and disinvested community. Perhaps the Emerson Collective is truly undertaking a form of “responsible development.” But the financing for the development has yet to be fully outlined, and whether or not a public–private (public–philanthropic) partnership can improve the economic situation of the city remains to be seen. The power wielded by the Emerson Collective and, by proxy, Laurene Powell Jobs lies not in its redevelopment methods, but rather in the speculative approach they have taken to community engagement, redevelopment, and economic growth.56 It has delegated public policy to an undemocratic body via what some have referred to as a “philanthropic plutocracy.”57 Until the Emerson Collective and its team provide full transparency around their proposal for the East Palo Alto Waterfront Development Project, many within the community, such as Bello, will continue to be wary of its benevolent intentions and of its impact on East Palo Alto. Beyond idealistic sentiments and illustrative examples of cultural precedents, this transparency needs to demonstrate how the project will be funded and how opportunities for housing and economic security will be provided in a community that has historically struggled for both.

Disruptive Development

The consequences of philanthrocapitalism for a city like East Palo Alto are tangible in the fact that the tech elite of Silicon Valley are eroding the potential for community-led reclamation of its urban fabric, threatening the very social transformation they purport to accomplish. Just like the philanthropic largesse enacted through the industrial wealth of the Gilded Age, the philanthrocapitalist undertakings of Silicon Valley billionaires are a symptom of the profound inequality of the profit-driven economy. While many philanthropic campaigns have shown that a market-driven charity can viably extend access to goods and services in communities lacking them, such altruism is effective only to a certain point and routinely fails to implement any kind of substantial impact or social transformation. Yet such criticisms seemingly fall short when one tries to denounce the noblesse oblige of philanthropists who may very well believe that they are providing good in communities that they see as lacking the services they have decided to provide. Therein lies the foundational conundrum of philanthrocapitalism. As Bello opines,

It starts to feel a little bit weird, because it almost feels like you’re not allowed to critique them. So, it gets very fuzzy, because they get so deeply ingrained into our community in these different ways that it’s hard to pull them apart. It’s hard to pull the people apart from the projects and the construction that’s going to affect us for generations to come.58

Programs such as The Primary School and Bloomhouse have extensive and long-lasting influence in areas such as education and urban policy, yet they are developed in the same manner as the start-up enterprises that Silicon Valley was built upon: as enterprises to be tested for measurable results before being brought to market. There is a concerning disconnect in the altruistic efforts of these programs’ benefactors and the acknowledgement that many of the disparities present in East Palo Alto—and which are present throughout Silicon Valley, such as inequities in the housing, job, and education markets—are all perpetuated through the very same success that led to the reality-defying wealth of the tech elite. The community of East Palo Alto and its leaders, such as Bello, are naturally skeptical of such projects. In a city that has had to fight for every development over the course of its forty-year history, East Palo Alto will champion only those initiatives that support and empower its people.

Office of the Press Secretary, “The Clinton Presidency: Unleashing the New Economy - Expanding Access to Technology,” The White House, Record of Progress, 2001. See ➝.

Jennifer Kavanaugh, “East Palo Alto: Clinton decries ‘digital divide,’” Palo Alto Online, April 19, 2000. See ➝.

Office of the Press Secretary, “The President’s New Markets Trip: From Digital Divide to Digital Opportunity,” April 18, 2000. See ➝.

To quote one of the journalists who covered the event, “At times the corporate presence at the event felt a bit heavy-handed. Members of an elementary school choir were decked out in T-shirts reading ‘Cisco Systems and Costaño School’ and sang a song for the audience praising its corporate sponsor.” Coile, “Clinton: Fight Poverty with Tech”,” SFGate, April 18, 2000. See ➝.

Carly Fiorina, “Remarks,” (speech, San Jose, California, April 30, 2003) Rainbow/Push Digital Connections Conference. See ➝.

Bill Clinton, “Remarks by the President in Digital Divide Discussion with the East Palo Alto Community,” Plugged In Event (East Palo Alto, California, April 18, 2000), Office of the Press Secretary. See ➝.

Coile, “Clinton.”

The term “philanthrocapitalism” was coined by Matthew Bishop and Michael Green in their 2008 book Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich Can Save The World. The book was endorsed by Bill Clinton, who wrote in its foreword that this concept drives the philanthropy of the Clinton Foundation.

Molly Wood, “East Palo Alto: Next door to Big Tech, vulnerable to climate change,” Marketplace Tech, September 20, 2019. See ➝.

Kim-Mai Cutler, “East of Palo Alto’s Eden: Race and the Formation of Silicon Valley,” TechCrunch+, January 10, 2015. See ➝.

Michael B. Kahan, “Reading Whiskey Gulch: The Meanings of Space and Urban Redevelopment in East Palo Alto,” Arcade: A Digital Salon 8, August 31, 2015. See ➝.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, East Palo Alto has a higher rate of childhood asthma than the rest of San Mateo County. Further, due to the explosion of high-tech manufacturing facilities across Silicon Valley, San Mateo and Santa Clara County have the highest number of EPA-monitored Superfund sites in the nation. Tara Lohan, “How a Silicon Valley City Cut Landmark Deals to Solve a Water Crisis,” The New Humanitarian, July 25, 2018. See ➝.

“20 years of East Palo Alto,” Palo Alto Online, September 10, 2003. See ➝. These dates differ between historical accounts, mostly due to bureaucratic differences in how the city was documented within the approximately 10-year span it took for the state to recognize East Palo Alto’s cityhood.

Kahan, “Reading Whiskey Gulch.”

See Olon Dotson’s examination of Fourth World Theory in Fourth World Nation: A Critical Geography of Decline (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2019), 72 – 85, for post-industrial parallels to Detroit, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana.

Don Kazak, “East Palo Alto, Whiskey Gulch comes tumbling down,” Palo Alto Online, April 28, 2000. See ➝.

Scott Wilson, “In East Palo Alto, residents say tech companies have created ‘a semi-feudal society,’” The Washington Post, November 4, 2018. See ➝.

Kristin D. Zeit, “Ravenswood Health Center John and Susan Sobrato Campus,” Healthcare Design, July 22, 2016. See ➝.

Shane Reiner-Roth, “wHY Architects’ new youth center in East Palo Alto will center the community,” The Architect’s Newspaper, September 13, 2019. See ➝.

Angela Swartz, “In the largest donation in Ravenswood’s history, foundation gives $30 million to build ‘community hub’ at middle school,” The Almanac, December 11, 2022. See ➝.

Iain Hay and Samantha Muller, “Questioning generosity in the Golden Age of Philanthropy. Towards critical geographies of super-philanthropy,” Progress in Human Geography 38, no. 5 (October 2014): 635-853.

Danny Dorling, “The Case for Austerity Among the Rich,” The Progressive Policy Think Tank, London: Institute for Public Policy Research (2012).

M. Bishop and M. Green, Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich can Save the World (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2008).

John Cassidy, “Mark Zuckerberg and the Rise of PhilanthroCapitalism,” The New Yorker, December 2, 2015. See ➝.

Vassilisa Rubtsova, “The Merits and Drawbacks of Philanthrocapitalism,” Berkely Economic Review, March 14, 2019. See ➝.

The Primary School, “Our Public Funding Plan,” The Primary School Organization. See ➝.

The Primary School, “Our Public Funding Plan.”

Emily Mibach, “School proposed by Mark Zuckerberg’s wife, Dr. Priscilla Chan, receives scrutiny,” Palo Alto Daily Post, December 25, 2018. See ➝.

The Primary School, “Our Public Funding Plan.”

Maggie Angst, “Private school founded by Mark Zuckerberg’s wife OK’d in East Palo Alto despite concerns,”The East Bay Times, June 20, 2019. See ➝.

Louis Hansen, “Working homeless forced to move in East Palo Alto,” The Mercury News, November 15, 2017. See ➝.

Emily Mibach, “The Primary School, founded by Mark Zuckerberg’s wife, leases abandoned school after dispute with sewer district over school’s favored site,” The Daily Post, July 17, 2020. See ➝.

Kali Hays, “Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan’s charity organization is making a major change in strategy after laying off 48 people.” Business Insider, August 9, 2023. See ➝.

Kali Hays, “Priscilla Chan says CZI is now a ‘science-focused philanthropy’ as its COO leaves,” Business Insider, published January 10, 2024. See ➝.

The Primary School, “About Us,” The Primary School. See ➝.

Carl Rhodes and Peter Bloom, “The trouble with charitable billionaires,” The Guardian, May 24, 2018, ➝; Rachel Dovey, “What Zuckerberg’s $100 Million Bought Neward Public Schools,” Next City, October 17, 2017, ➝; Steven Melendez, “After rapid growth, Zuckerberg-backed school program faces scrutiny over effectiveness, data privacy,” November 19, 2018, ➝; Nick Tabor, “Mark Zuckerberg Is Trying to Transform Education. This Town Fought Back,” New York Intelligencer, October 11, 2018, ➝; Nellie Bowles, “Silicon Valley Came to Kansas Schools. That Started a Rebellion,” The New York Times, April 21, 2019, ➝; Matt Barnum, “Mark Zuckerberg tried to revolutionize American education with technology. It didn’t go as planned,” Chalkbeat, October 4, 2023, ➝.

Emerson Collective, “East Palo Alto Waterfront Project: Area Plan Project Vision,” December 15, 2021. See ➝.

Sarah McBride and Gerry Smith, “Laurene Powell Jobs’ Foundation Becomes a VC Machine,” Bloomberg, April 25, 2019, ➝.

David Montgomery, “The Quest of Laurene Powell Jobs,” The Washington Post, June 11, 2018. See ➝.

Elisa Lipsky-Karasz, “Laurene Powell Jobs is Giving It Her All,” The Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2022. See ➝.

Lipsky-Karasz, “Laurene Powell Jobs.”

Bloomhouse, “About Emerson Collective,” ➝.

Dremann, “Laurene Powell Jobs buys 30 acres.”

Emily Mibach, “Steve Jobs’ widow unveils large development,” Palo Alto Daily Post, September 20, 2020. See ➝.

Emerson Collective, “East Palo Alto Waterfront Project.”

Patty Rally, “Center for Economic Mobility Receives Approval From City of East Palo Alto Planning Commission,” JobTrainWorks, January 25, 2022. See ➝.

Emerson Collective, “East Palo Alto Waterfront Project.”

Bloomhouse Representatives, “Bloomhouse and the East Palo Alto Waterfront Development Project Interview,” interview by Leigh House (2023).

See Luis Suarez-Villa’s Technocapitalism: A Critical Perspective on Technological Innovation and Corporatism chapter on “Creativity as a Commodity” (2009 p. 31-55).

Jeremy Beer, Philanthropic Revolution: An Alternative History of American Charity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 85–90; Angela Eikenberry and Roseanne Mirabella, “Extreme Philanthropy: Philanthrocapitalism, Effective Altruism, and the Discourse of Neoliberalism,” American Political Science Association (January 2018), 43 – 45.

A similar record of East Palo Alto’s history was funded and published by Romic Chemical Corporation for the city’s tenth anniversary in 1993.

Ofelia Bello, Zoom interview with Leigh House, August 24, 2023.

The Washington, DC “Gentrification Proof” pavilion designed in collaboration with the Emerson Collective, Redbrick, and architect David Adjaye, as well as the public concerns about the “California Forever” Solano County development recently announced by the Flannery Associates, further exemplify the trend of speculative “social impact” development that Powell Jobs has been undertaking.

Joanne Barkan, Dissent Magazine, October 22, 2013. See ➝.

Bello interview, August 2023.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.