Andres Lepik: The Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin was originally designed as a congress hall, which is a different purpose than it serves today under your directorship, and which it has served for the past few decades. Do you see this as an opportunity, or a challenge for your work?

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung: Things are not necessarily limited to being either a challenge or opportunity. They are often both. There are times when the building is a great challenge, while there are other times when it is an opportunity because it forces us to think differently. If you’re working within a space that is meant to be a conventional exhibition space, a kind of white cube, it’s very evident, very predictable, so it doesn’t challenge you; you show things in very habitual, normative ways. But I’m interested in the abnormal, in the non-habitual, and the difficulties that arise from working in those ways. I think that it’s a challenge and a chance at the same time.

Łukasz Stanek: The building was originally a gift from the United States to West Germany as part of the Interbau exhibition of 1957 and within the overarching context of the Cold War. In that sense, as a diplomatic gift, it has a double character. It’s both amicable and antagonistic. How do you work with that legacy?

BSBN: This amicability and antagonism is something that is not only in the history of the building, but is also present within the building itself. As an institution of power, the building is inviting towards a certain kind of people and is disinviting towards another kind of people. When I came to Berlin in the 1990s, I had difficulties visiting the building and the institution because it felt so symbolic and uninviting. It’s built in a way that the audience can’t get there on foot. You come in through this long driveway, which is designed in such a way that you exit your car at the main entrance and immediately step onto the red carpet, so to speak. For many people, that is quite imposing. It’s inviting towards diplomatic circles, but not for normal people. Further, in the history of the institution, you have the fact that it was given to West Germany as a sign of friendship. But it was also meant to send the communist part of the then-divided country a message: “Look, this is a sign of Western democracy. This is a sign of Western freedom.” The roof was meant to resemble a pair of wings. I don’t really know what that romantic notion of democracy means, but I do fully well know that it was a machination, a ploy. This sociopolitical, politico-architectural history finds itself in our program.

ŁS: How so?

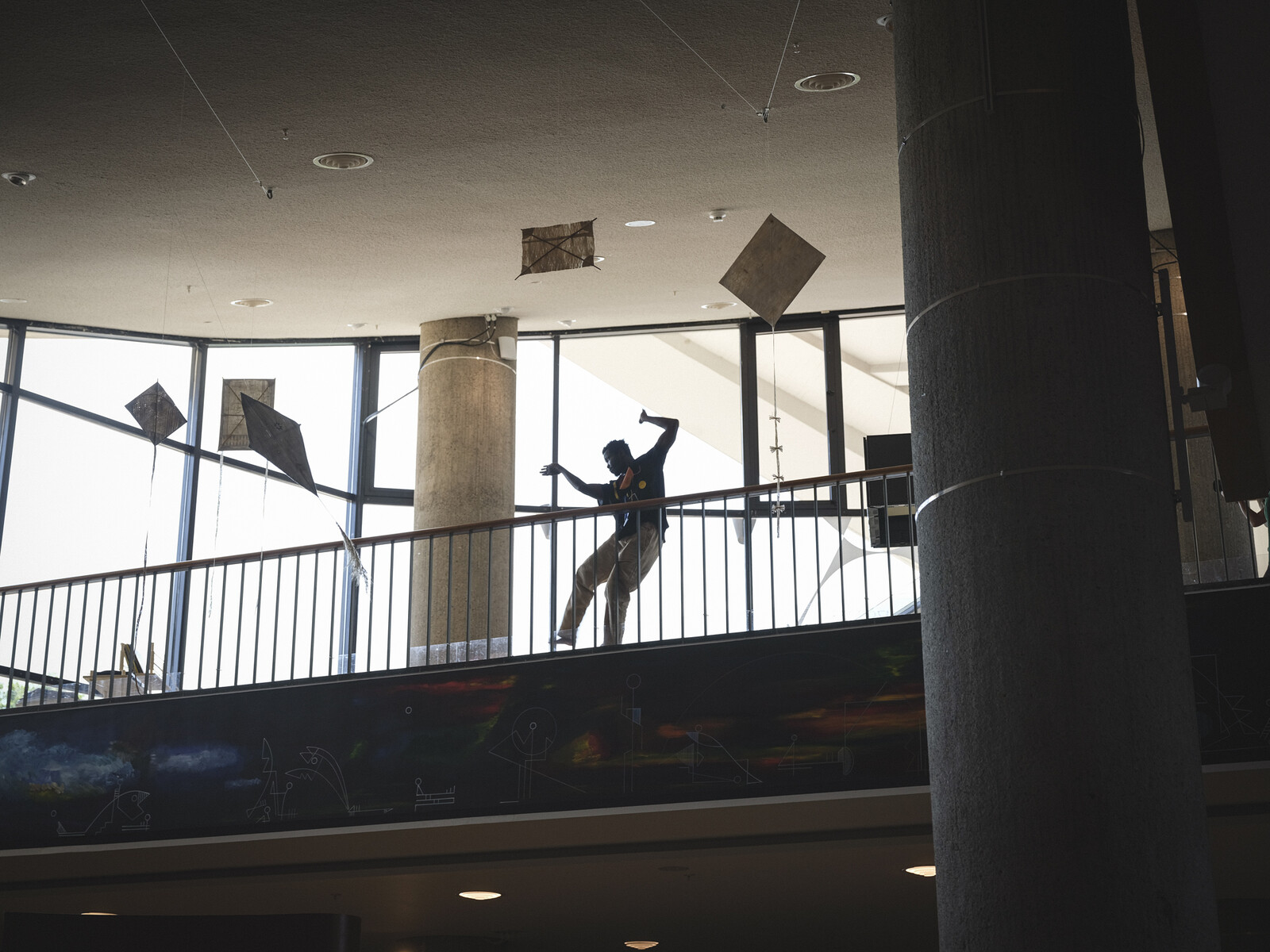

BSBN: The whole notion of the building being a congress hall could seem frightening for somebody who is only interested in making exhibitions. But since we have a strong interest in performativity, I wanted to work with the etymological meaning of a “congress.” It comes from the Latin word congredi, which means to come together, to meet. So the idea we are working with is to extend a gesture, to say “come be/become with us.” We wanted to put emphasis on that through the installation of works as well as through the activation of spaces. Entering into the building, you arrive in the foyer, which is a circular space with heavy pillars that carry the structure of the building. We have always sought to work against this hardness by working with it. There are these huge waves in the Atlantic, or really any big ocean, and if they catch you, you cannot fight against them, otherwise they will kill you. You just have to allow them to carry you. So we cannot fight against such a structure. Our question, then, is how to dance with it? Basically, we’re trying to work with the architecture, to play with it, to find its soft spots and placate it. Like everything else, architecture has its soft spots, and, in our exhibitions, we’re trying to find them. For instance, in our opening exhibition O Quilombismo (2023), we displayed a series of sculptures by Oscar Murillo in the auditorium, floating from the ceiling. The auditorium thus became not simply a place where you can come and see a performance or listen to a concert, but it actually became a pedestal, an exhibition space. We also installed a sound installation there, which people were able to visit every day.

ŁS: The Cold War also had repercussions in Africa and Asia, and the German Democratic Republic (GDR)—the country to which the ideological message of the Congress Hall was directed—was significantly involved. In your programming, the HKW has been uncovering relationships between the GDR and Africa and Asia, and often in a very sympathetic manner. Do you see programming as an opportunity to reposition the venue towards its own history?

BSBN: When we started working in this institution, one thing we noticed in the archives was that there had been very few programs that related to the GDR. This reality isn’t specific to HKW, but is the case in many formerly West German institutions. Having lived in Germany since the 1990s, I am of the opinion that the history of that other part of the country has not only been overlooked, but has been engulfed by a larger narrative of the “Bundesrepublik Deutschland,” which tells the story of a successfully reunified Germany from a predominantly West German perspective. We think that there’s an important part of German history, and world history, that hasn’t been told but needs to be. That’s why we started working on this exhibition and research project called Echoes of the Brother Countries (2024), which looks at the alliances and agreements made by the GDR with other socialist and socialist-friendly nations like Ghana, Angola, Vietnam, Cuba, and so forth. More specifically, it looks at how this history and the amnesia surrounding it continue to shape Germany and its so-called “brother” countries’ demography, culture, economy, and politics, as well as the lives of those who migrated under the conditions of the Eastern alliances.

AL: How have you undertaken such a project, worked with such histories?

BSBN: What we’ve tried to do is not just sit in Berlin and fantasize about these things but actually go to those places and work with researchers there. We’re working with Hanoi Ad Hoc in Vietnam, an architectural research group that is interested in the relationship between Germany and Vietnam and the way it manifests itself, for example, within architecture and the spaces that have been created by Vietnamese people who returned after living and working in the GDR. We have colleagues that have gone to work with people in Chile, in Algeria, Cuba, Ghana, etc.

Exhibition view of As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design/2050+. Photo: Studio Bowie/HKW.

Installation view of the exhibition O Quilombismo: Of Resisting and Insisting. Of Flight as Fight. Of Other Democratic Egalitarian Political Philosophies, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Photo: Laura Fiorio/HKW.

Installation view of the exhibition O Quilombismo: Of Resisting and Insisting. Of Flight as Fight. Of Other Democratic Egalitarian Political Philosophies, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Photo: Laura Fiorio/HKW.

Exhibition view of As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design/2050+. Photo: Studio Bowie/HKW.

AL: How has this been received so far, publicly?

BSBN: When we did our first press conference in March 2023, a journalist asked: “Now you’ve brought these people from around the world and they’re all sitting on stage, that’s fine, and you’ve talked about the east, and that’s fine, but where is West Germany in your program?” It was fascinating to see how threatened he felt, as if the western part of the country had been forgotten. My response was very simple. I said: “The architecture, the institution is still located in what was West Germany.” I told him that he shouldn’t worry because in the history of the institution, the Western world is constantly being remembered. But the question is, how to tell all the other stories? In a short text that I wrote for the HKW’s program newspaper, I went back to an old, over-cited text by Stuart Hall on “The West and the Rest,” and I was playing with the idea of what the West is.1 I’m currently moving away from the whole idea of the Global South. What does that actually mean? I’m intrigued by the provocation of what I like to call “the Global East”. What does it mean if we try to narrate these histories from this other vantage point? The Cold War was happening in Angola, in Cameroon, and other places. We became battlegrounds of a war that had little to do with us.

AL: To go back to what you said already about democratization, democratization was, let’s say, put into the DNA of the building when it became a gift. Do you think this gift, this DNA of democratization, has expired now? Or do you think that, in the present moment in Germany, when the right-wing is gaining more power, this DNA is still valid for your work and for the program in general?

BSBN: That’s a good question. I want to try and be careful, because I think that the right is also part of the DNA of democracy. So what does that mean? If democracy is in the DNA of the building, how is it reflected? It’s in the words of Benjamin Franklin, written on the walls of the building, in which he hopes that every “philosopher may set his foot anywhere on its surface and say ‘this is my country’.” This is a very tough thing to say in a colonial context. Who is the philosopher? What power does the philosopher have to claim a land just because of setting foot there? Although it is meant to be a liberating democratic measure of things, that, to me, is fascistic. That’s how I see it. The building served its purpose, I would dare say, as a tool of propaganda. That’s why it’s surrounded by these different props, like the John Foster Dulles Allee. All these different things tell different stories about the building. In what way, then, can we consider this a symbol of democracy, knowing that many members of the Dulles family, including John Foster, were involved in several coup d’états around the world, from Iran to different countries in Latin America and on the African continent? To me, it’s very complicated. That particular notion of democracy might fit a certain context, but is not necessarily applicable to others. It’s not a panacea. It’s not a one-size-fits-all.

AL: How do you reflect on and work with these contested and plural ideas of democracy within your program?

BSBN: One of the projects we’re trying to conceptualize for the next years is titled “Conjugating Governances,” in which we’re thinking about the different models of governing and governance. What does governance mean in indigenous communities around the world? Can we take the idea of democracy as it is conceived in France or in the US and impose it on another country or another geography? I just came from a visit to the Bernard Dadie Archive in Abidjan. One of the things I read there, to paraphrase, was about the fact that for people to be able to exercise democracy, they must first be informed about humanity. Which is to say that if people are acting on inhumane values, they cannot practice democracy. The right wing and the contemporary rise of fascism goes back to that period of Benjamin Franklin, when certain people were considered more human than others, when the humanity of certain people wasn’t accepted, when certain places could still be declared terra incognita.

ŁS: The connections and exchanges between socialist and postcolonial countries were often—perhaps always—asymmetrical and unequal. And yet, even within an asymmetrical and unequal situation, there is the possibility of an opening, of an emancipatory potential. The Haus der Kulturen der Welt is a venue that captures various ideological differences and very real antagonisms. How do you deal with this?

BSBN: What inspires us is the negotiation of those asymmetries. Liberation or emancipation is a practice. It’s not given. It never ends. The struggle never ends, so it must constantly be activated and reactivated. That is very much the basis of the work we do. We just need to look left and right to see that whenever some people stand up to resist the dehumanization that is enacted upon them, that dehumanization gets even more violent. This violence manifests itself within space. House and street names are a good example of this. What does it mean to stand in front of a house called “von Trotha,” knowing full well that Lothar von Trotha executed the genocide of the Hereros and Namaquas in German South West Africa (now Namibia)? What does it mean to walk along a street called Wöermannkehre, knowing full well that, even before the 1884 partitioning of the African continent, there were Wöermann Factories across Africa and around the world? Or streets named after colonialists like Adolf Lüderitz, Graf Spee, or Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, and many more? This history of violence is omnipresent. For some people, it is not seen. But for others, it is felt. That’s why I’m interested in spatiality at large. That’s why I care about the socio-politics of space. We are sensitive towards the rights of humans and how the arts can play a role in telling some of these stories. Coming back to the idea of storytelling, how do we actually use these spaces to tell stories, bigger and smaller ones alike?

Stuart Hall: “The West and the Rest. Discourse and Power” (1992), in: Essential Essays, Volume 2. Identity and Diaspora, Duke University Press 2018.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.