After driving through the main gate of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana, visitors are welcomed by an expansive view: a vast meadow crossed by a meandering river and framed by university buildings. That landscape was conceived by the British architect James Cubitt in the early 1950s, when the government of the then-British colony of the Gold Coast founded a College of Technology in Kumasi, the former capital of the Ashanti Confederacy. In Cubitt’s master plan, the campus was carved out from what colonial planners saw as tropical “bush,” giving credence to the university’s maxim “from forest to faculty.”1 Today, its vistas contrast with the dense fabric of surrounding towns and scarce vegetation.

Satellite image of the KNUST campus, 2023.

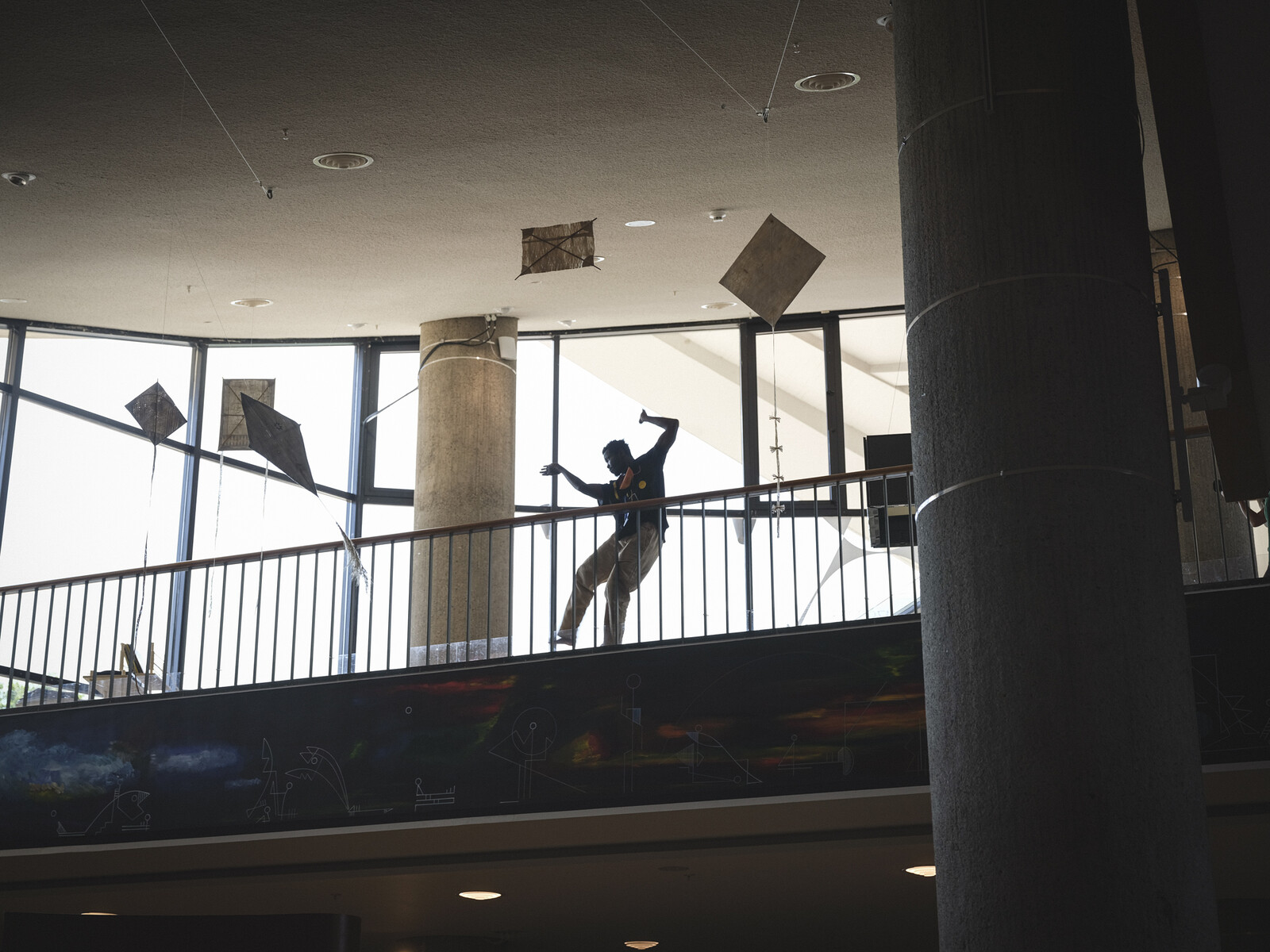

While Cubitt’s design has been modified by a string of others, visitors continue to experience the campus according to the principles set out by its first master plan. As one rides across the Wewe River and climbs up towards the old part of the campus, the modernist student housing towers reveal themselves before receding behind a backdrop of classrooms, laboratories, administrative offices, and service buildings. Further to the west, the master plan foresaw bungalows for senior employees. Driving along the road that gently bends in parallel to contour lines, one bungalow disappears in the rear mirror as another emerges from behind trees and decorative shrubs.

Like in other educational enclaves in post-war British West Africa, the driver’s view was privileged by colonial planners. Getting out of the car is therefore the first step towards reading the master plan against the grain. Walking on the roads, one sees few pedestrians: only a small number of service workers, laborers, and people carrying agricultural tools, sometimes also big bundles of cut grass. While at first glance these people may seem like gardeners tending to the manicured lawns, a walk along the edges of the bungalow area makes clear that they are farmers. Around the walls of the campus and from the bridge over the river, one can see people farming plots with lettuce, cabbage, spring onions, and other cash crops.

Once noticed, farmers seem to be everywhere at KNUST: on the land between the botanical garden and the eastern edge of the campus; in the banana groves around housing units for university staff, Hall 6; and along the untarred road connecting the recently constructed buildings of the School of Business to the town of Gyenyase. Besides the university’s own experimental farms supervised by the Faculty of Agriculture, individual farming activities were not foreseen by the Cubitt plan, nor by the plans that followed. The presence of farmers reveals an ecology defined by agricultural production that ties the campus to the towns and villages nearby.

This was confirmed in interviews with several farmers who are working on the university land, all of whom live in nearby towns: Kofi lives in the village of Kuntanse; Moses in Atonso; Madam Naa, Evans, and Charles in Kotei; and Akwasi in Gyenyase.2 Most sell their produce to women traders who then resell it in the open markets of neighboring towns. The university administration sees them as “small gardeners” rather than farmers.3 People farming the land share a sense of precarity: Kofi expects to be removed from his plot at any time, whenever the university decides to construct a building or infrastructure there.4 Madam Naa, who sells food items to construction workers on campus while also planting corn, cassava, and plantain for subsistence, relocates her stand every time the workers move from one construction site to another.5

And yet, these farmers have been farming on campus land for a long time. Some have worked the land for as long as eighteen years; others took over plots from people who had been farming them for decades. University records provide evidence of conflicts over land during the 1970s, when administrators mediated between farmers from the neighboring towns and lower level employees of the university, who cultivated the land and collected firewood in order to supplement their modest income.6 Even older documents reveal that such conflicts went back to the foundation of the campus. Farming on campus is therefore not a new development unforeseen by the master plan. Rather, it was the master plan that disrupted an older ecology of agricultural practices.

A historical study of farming on campus challenges not just the decisions of the colonial master plan, but also its premises. Archives in Kumasi, Accra, and London show that during the early 1950s, colonial administrators considered several sites in and around the city for the location of the future College of Technology. Their decision to choose the current site was based on an evaluation that it was sufficiently large and empty. Another advantage of the site was the availability of water from the Wewe River, an inland water body that takes its source from the mountains near Aboabo Nkwanta and flows for about twenty kilometers southwest of Kumasi. The proximity of both the road and the railway line connecting Kumasi and Accra were essential for the transportation of construction material, machinery, and professional labor to the site. Workers, however, were expected to be recruited from the neighboring villages. Only later did the planners realize that these prospective workers had a long relationship with the land of the future campus: they buried their dead in it, gathered firewood on it, and farmed parts of it.

If the land was not empty, it needed to be cleared. Its clearing followed an agreement with Nana Sir Osei Tutu Agyeman Prempeh II, the fourteenth Asantehene, or the king of the Asante people within the British system of indirect rule. During the late colonial period, lands in the Ashanti region were divided into two categories: “crown” land and “stool” land (with stools being the traditional symbol of political, judicial, and social leadership of the chiefs). Stool land belonged to the Asantehene, with divisional chiefs acting as its caretakers. Responding to both persuasion and pressure by the colonial administration, the Asantehene agreed to make the land available to the college and convinced the caretaker chiefs to endorse his decision. Prempeh II leased the land for sixty years to the colonial government, which then passed the lease on to the college.

The lease agreement included compensation for the caretaker chiefs as well as for farmers who were required to vacate the land. Farmers whose crops were destroyed by the construction work were paid compensation. Disputes about the eligibility and extent of compensation went on for months, and letters between colonial officials and farmers included detailed discussions about particular cassava plots or individual cola trees. However, farmers were not compensated for the fact that they could not farm the land in the future, and some of them decided to leave the area to search for farmland elsewhere.

In 1953, the land was sufficiently cleared for the then-principal of the college, Dr. J. P. Andrews, to present himself and his team as “pioneers” who were taming tropical bush. During his speech at the Admission Ceremony on October 31, 1953, Andrews emphasized that the new buildings of the college, “the finest in Africa, possibly in the world,” were standing on a site that a year before had been merely a “forest country.” He thanked the Asantehene for this “generous gift” of land on which the college was built.7

Andrews’s use of the term “gift” to refer to land that, in fact, was leased, was not intended to challenge its legal status. Rather, his use of the term reinforced the assumption that the college was built on vacant “forest country.” It assumes either the absence of other claims to the land or the possibility of eliminating those claims efficiently before the land was taken over. By using this term, Andrews emphasized the legitimacy of the college’s claim to occupy the land and reinforced it through the prestige of the Asantehene. In so doing, he might have intended to direct any possible disquietude among local communities about the lease towards the Manhyia Palace (the seat of the Ashanti monarchy), rather than towards the colonial government.

In the following years, several officials of the college, then the university, continued to refer to the land as a “gift.” This term was also used by inhabitants of the neighboring towns who embraced the moral economy implied by the practice of gift-giving and who claimed that the obligations of the university needed to be expanded to community members who had not been included in the initial compensation schemes. This narrative still reverberates today. According to one retired worker from the town of Ayeduase, west of campus: “My parents were farmers. They grew cassava and maize. The university took land from them… The university should be helping us—the whole town, not only those who owned land.”8

The university acknowledges that it has obligations towards these communities—sometimes with direct references to the land taken over and sometimes based on other arguments, such as the increasing intertwinement of the everyday lives of students and staff, on and off campus. Since the 1950s, the university has been offering jobs to those in the neighboring towns and villages, and occasionally shares access to social and technical infrastructure.9

The presence of farmers on university grounds is a constant reminder of that moral economy. In particular, it is a reminder of what people in the nearby towns have never forgotten: that this land could have been used in different ways and for different purposes. Given the recent renewal of the lease for another fifty years, the takeover of the land by the university is not an event of the past but rather an event that continues to take place every day. Since land in Ashanti cannot be alienated from its community, its ongoing use by KNUST comes with ongoing obligations towards the towns nearby. Many inhabitants emphasize these obligations; in the words of one chief, “the university continues to use our land, so they need to continue to support us.”10 The continuous presence of farmers within the boundaries of the university offers a starting point for reimagining its future beyond the colonial master plan in ways that acknowledge the intertwinement of the campus with the surrounding towns.

The phrase can be traced to Dr. Ephraim Amu’s Ayan poem, which served as the drum call in the pioneering years of the university. “From forest to faculty” is also the title of the documentary commissioned in 1977 by the university and directed by the Ghanaian cinematographer Charles Owusu. The appellation also served as the subtitle for the Opoku Ware II Museum’s (also known as KNUST Museum) exhibition that opened on November 24, 2019, with the theme “Dignity in Labour: From Forest to Faculty.”

Interviews by Bright Ahadzivia and Korkor Ebeheakey (April-May, 2023) and Korkor Ebeheakey with Łukasz Stanek (June 2023). Assistance by Joshua Cann Lamptey.

Interview (anonymized) by Łukasz Stanek, June 2023.

Interview by Korkor Ebeheakey with Łukasz Stanek, June 2023.

Ibid.

Letter from Martin Nobio, May 26, 1972.

J. P. Andrews, “Principal’s Address,” October 31, 1953.

Interview (anonymized) by Łukasz Stanek, March 2022.

The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, February 28-September 8, 2024, curated by Damjan Kokalevski and Łukasz Stanek.

Interview (anonymized) by Łukasz Stanek, March 2022.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.