In the second half of the twentieth century, Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, experienced a significant transformation in its infrastructure and housing. Situated between two powerful nations, Mongolia has received aid and gifts from both Russia and China, as well as previously from the Soviet Bloc. Following the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1949, the People’s Republic of China provided Mongolia with socio-economic assistance. However, due to the deteriorating relationship between China and the Soviet Union, the Chinese government halted construction projects in Ulaanbaatar in the early 1960s.

In 1964, the National Institute of Construction and Building of Mongolia produced three types of comprehensive urban plans for the city, including for housing microdistricts (microraions). In 1966, after Leonid Brezhnev’s inaugural visit to Mongolia as the General Secretary of the Communist Party, the two countries signed a mutual assistance treaty. This treaty marked the beginning of a new phase of urban development, characterized by extensive infrastructure development and the construction of apartment buildings across Mongolia, particularly in Ulaanbaatar.1

Brezhnev visited the country again less than a decade later for the fiftieth anniversary of the Republic of Mongolia. The visit was highlighted by a bilateral treaty signed on November 27, 1974, which involved the Soviet Union gifting large development projects to Ulaanbaatar, including two factories for prefabricated buildings and the 3rd and 4th housing microdistricts, among other things. The Soviet Union mobilized its architectural and planning institutes and sent engineers and construction workers to Mongolia for the four-year development program, which lasted from 1976 to 1980. This Soviet assistance was much larger in scale compared to similar projects offered by the Chinese Government, which were mostly based on loans and trade-in deals.

The 3rd and 4th microdistricts, located in the western Bayangol district of Ulaanbaatar, were fully funded and built by the Soviet Union. Constructed by the Construction Trust No. 2 from 1976 to 1987, they were affectionately referred to as “Brezhnev’s gifted blues,” due to their distinct blue color.2 Their construction was part of a broader effort to modernize Mongolia, redevelop vernacular ger areas (semi-formal settlements named after the nomadic felt dwelling), build infrastructure, and improve the living standards of the city’s laborers. As part of a communist propaganda program to increase Soviet influence in Mongolia, the development and opening of the microdistricts was highly visible in newspapers. According to a report about the opening and occupation of the districts:

In the socialist development of our country, there isn’t a single field where a Soviet brother’s intelligence and labor wasn’t a part of. We Mongolians reap the benefits of the kind support and collaboration between our two nations every single day. Therefore, to look after this newly constructed microdistrict, is our solemn duty.3

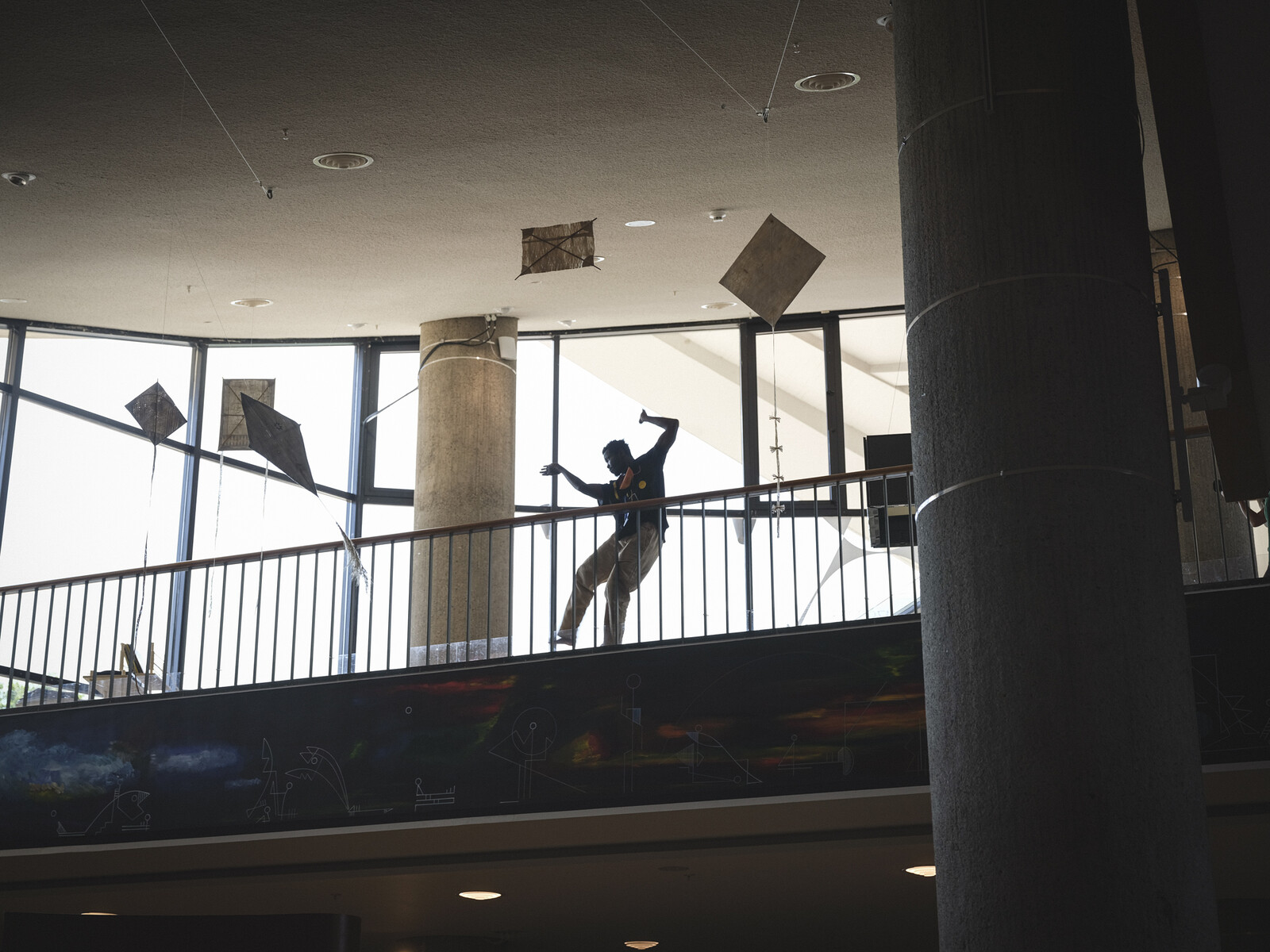

Families working across the city were given their first apartment in these microdistricts. Government, hospital, military, as well as factory workers were among some of the families who moved into this new neighborhood. Some now recall feeling that walking its streets was like being in a foreign country, and referred to it as “new Moscow.” The district was originally called the Oktyabr Raion, named after the October Revolution of 1917, and the main street was called Brezhnev Avenue. It was the largest microdistrict in Ulaanbaatar, complete with amenities such as kindergartens, schools, hospitals, public transportation, a movie theater, and shopping areas.4

The convenience of living in apartments was a gift in itself for many. Stories about daily life in the apartments created new idioms, like describing “tap water” as “fetching water from a wall.” Other new residents, however, needed time to adjust to a life “confined within four walls,” in contrast to their small but homey ger.

“My friends who would visit our home would complement us on how nice our complex is and how it looks like something they only heard from people who traveled abroad, with everything you need at the palm of your hand,” recalls Yanjiv Sodovsambuu, 75, who was given an apartment in the 4th microdistrict, as her husband was a healthcare worker in the state hospital.5

During this period of development in the city, workers had to submit a request form to their employers and wait to be offered housing, as all agencies were only given a certain quota of apartments for employees. Each agency had different criteria for selecting who got which apartment and when, though they often prioritized those who did not have an apartment to begin with.

Even though families came from different provinces, backgrounds, and workplaces, after being selected as one of the recipients of a unit in this complex, they were united by a new sense of responsibility. As soon as families moved in, associations were formed to conduct routine cleaning and neighborhood watches, and rules were developed that applied to everyone.

“Back then, our neighborhood had arranged patrols around our apartment. We had apartment leaders who were in charge of coordinating cleaning and other neighborhood tasks. Nowadays, this practice is missing, and I believe that people living in the same place should take responsibility for such matters,” recalls Dashbal Yunden, 81, a member of one of the first families to move in 1978.6

The story of Chimed Damdinsuren and his family’s three-generation connection to their unit within “Brezhnev’s gifted blues” illuminates the broader narrative of Mongolian families and their relationships with their homes. It underscores the resilience and adaptability of the first generation of gifted-apartment residents, who embraced the transformations brought by political and social change. The stable home was an enduring presence and played a significant role in shaping their lives and fostering a sense of belonging.

First Generation: Chimed Damdinsuren

As a concrete plant worker in Soviet-era Mongolia, Chimed Damdinsuren, who was 34 years old in 1981, was among the thousands of Mongolians who were awarded new apartment units in the capital city’s 3rd and 4th microdistricts. Born and raised in a herder’s family tending animals in the boundless steppe, with this gift, like many Ulaanbaatar residents at that time, Chimed settled into an apartment for the first time.

Previously, Chimed and his family of six lived in a ger (a nomadic felt dwelling) in a neighborhood of gers in the south-western part of the city, Yarmag, which had no heating, running water, or roads. Moving into their nine-story building in the heart of a new housing district close to downtown was his family’s first experience of living in a modern apartment with running water and central heating. The forty-five square meter apartment, which had a bedroom, living room, and kitchen, was much larger than his ger of 18.9 square meters. Gers had minimal furniture, which was convenient for nomadic lifestyles, so furnishing apartments was another new experience for Mongolians like Chimed. But many carried their culture and religion with them:

When we first moved in, along with the apartment, we were gifted a stove like every other family who received an apartment. It symbolized eternal fire and a central pillar of our household. As our building was new and the elevator wasn’t even operational, I carried the stove on my back up to the third floor. That was the only piece of furniture we had moving in.7

Chimed Damdinsuren outside of the entrance of his gifted apartment, 2023. Photo: Baljmaa G.

As parents of four young children—Altankhuyag, Ariungerel, Ariuntuya, Bayarsaikhan—Chimed and his wife were immensely grateful for the social amenities that were built along with the apartment. Previously, there was only one school in Yarmag, and he took turns with his wife taking the kids to and from school. After the move, however, everything was within walking distance, which helped them spend more quality time together as a family.

The Soviets designed microdistricts as self-contained entities, which offered everything residents needed within walking distance. Chimed fondly remembers the Soviet engineers and architects who constructed infrastructure and housing projects in Ulaanbaatar, referring to them as “our brothers.” It was common and celebrated knowledge among all of his neighbors that the microdistrict was part of a bigger gift to Mongolia by Brezhnev and the people of the Soviet Union:

I feel grateful for our apartment in two ways: I feel gratitude to the Soviet Union for building the many apartment complexes and gifting them to the people of Mongolia. I am also very proud of and grateful for the Mongolian government, the factory I was working for, since they are the ones who actually prioritized our family to gift the apartment.8

Today, over forty years later, Chimed and his wife continue to reside in the same apartment building in Bayangol district, now with their daughter, two grandchildren, and a great-grandchild.

For Chimed and his family, the apartment complex holds significant historical and personal value. It symbolizes the efforts made by Soviet “brothers” to modernize Mongolia’s infrastructure and improve the lives of its citizens. At the same time, it also represents the family’s journey through systemic changes and growth over the years. The gifted apartment unit is now filled with cherished memories of the whole family. It has witnessed family milestones, such as raising children and the birth of their grandchildren and great-granddaughter. It has become a treasured family heirloom.

Second Generation: Ariungerel Chimed

Ariungerel’s family embraced their new apartment with a sense of pride and gratitude. Her mother would often recount how her father’s diligence as a factory worker earned them this home. This narrative instilled a strong work ethic and appreciation for what they had in Ariungerel and her siblings.

Living in a mass housing complex meant being part of a tight-knit community. She recalls how her building housed not only Mongolians, but also Soviet families working in various capacities across the city. In contrast to the fenced-in plots and narrow streets of ger areas, the playgrounds and open spaces between buildings in the microdistricts created spaces where they often played as children. Oblivious to the external world, they would share moments of joy and camaraderie:

We used to play in the playground for hours on end, Mongolian and Soviet children all together. Until they moved away when I was in my third grade, we played together despite not speaking the same language.9

One of the biggest shifts in Ariungerel’s daily routine after the move was how she spent her free time. No longer needing to help with household chores like looking after younger siblings or fetching water from the kiosk, she had much more time to play and learn. There was an arts and sports complex for children in the district, where she and her friends spent time learning new skills.

Children were the backbone of the community. They not only went to the same new school, but they were also neighbors, classmates, and friends who knew each other’s families and formed close bonds. Because their parents worked and a variety of social amenities were located nearby, children grew up to be independent, needing minimal supervision. Ariungerel’s view about the apartment differs from her father’s:

I consider the apartment as a gift from the Mongolian government but am more grateful for the people at my father’s workplace who prioritized my family to give us the apartment when they had many other workers. Because I was young, I had little knowledge of the apartment being a gift from the Soviets, which I became aware of later on. Even with that knowledge, it was the people who chose us that ultimately affected our lives.10

The winds of change swept through Ulaanbaatar and beyond with perestroika, a political reform movement initiated by the Soviet Union’s Communist Party as an effort to end the Era of Stagnation. The 1990 Democratic Revolution, led by young Mongolians in their late twenties and early thirties, launched the country’s brave but painful transition to democracy and a market economy. As these changes unfolded and the Soviet Union collapsed, the USSR pulled its work force from Mongolia. Power plants in Ulaanbaatar ran out of coal and power outages became more frequent throughout the country. Basic commodities became scarce, and monthly food coupons had only a few items, including bread, salt, and a bottle of vodka for each household.

The Soviet families that departed the neighborhood left behind empty apartments. This prompted great changes in the neighborhood: what was once a lively and vibrant neighborhood turned into a quiet, abandoned place. As a teenager, Ariungerel witnessed her friends and neighbors moving away, seeking ways to stay afloat:

At the time, I was just sixteen years old. My worldview had just been somewhat shaped, and then I had to change it again. Things were much more difficult, and you had to work harder to live. I remember reminiscing about how straightforward life was during the Soviet-era.11

Following the peaceful revolution, Mongolia’s new constitution was passed in 1992, declaring the right to own private property. But it took approximately four years for that to apply to the people who had been given their apartments.12 In 1996, their homes were valued, and residents came to own them through privatization vouchers allocated to each apartment owner. Residents finally became familiar with private property with a price tag. During this time, Ariungerel and her family saw their friends and neighbors sell and trade their apartments in an attempt to manage chaos and uncertainty. Their family, however, held onto their home and did not move away.

Over the years, Ariungerel became a mother, giving birth to her children—Ankhiluun, born in 1994, Temuulen, born in 2001, and Telmuun, born in 2010—all of whom grew up in the same apartment. The political and economic transition of the 1990s created turmoil in Ariungerel’s neighborhood. It became more and more crowded, tightly packed with poor quality buildings and no planning. Second-hand cars, imported mostly from South Korea, replaced Soviet ones. Though life was completely different from when she first moved there in 1981, their family home provided a sense of safety and security during the tumultuous times of the transition:

Becoming a mother made me appreciate the value of having this home. If my dad had not been given this home, perhaps life would not have been easy for me or my children.13

Ariungerel chooses to preserve her family home. It holds memories of her childhood and family. For her brother, who has lived abroad for twenty years, the only connection to his hometown is the family home.

Third Generation: Temuulen Enkhbat

Instead of attending kindergarten, Temuulen was homeschooled by her grandmother and grandfather. They created memories by spending time together in their home and exploring the neighborhood hand in hand. In contrast to her mother’s childhood, she has few recollections of playing outside with the neighborhood children. Instead, she often spent summers at the family’s summer house, away from the bustling of cars and building sites.

As a recent graduate in urban planning, Temuulen has witnessed rapid changes in her neighborhood, particularly its transformation over the past decade into a bustling commercial district. This surge of commercialization has driven heavy traffic into the once secluded neighborhood. However, commercial activities were always a part of the life there:

One of my favorite childhood activities was shopping with my grandma in the neighborhood. It was convenient because we had many shops close to our home. I remember when I did my exchange semester in a suburban American college town, going to get groceries was such a hassle. I missed the convenience of going downstairs to grab bread or shampoo back at home.14

Growing nightlife and pubs brought in drinking and reckless behavior. Over the years, as a young woman, Temuulen’s sense of safety in the area has deteriorated. Additionally, sharing the same roof with multiple generations of family members, as well as her work and everyday life being almost entirely in the city center, has led her to occasionally contemplate moving out of the family home.

Temuulen now reflects on the rare privilege of living under the same roof as so much of her family and of her continuing close bond with her grandparents, cherishing these moments while they last. She shares her apartment with five other members of the family. When her parents are in town, they take turns sleeping in the living room.

She only recently became aware that their family home not only came from the Soviet Union, but that it was a gift. From the perspective of a granddaughter who was raised by her grandparents and who looks after them in the same home, she expresses gratitude for them and their strong attachment to this home:

I had very little knowledge about who and how this apartment was constructed and was gifted to my grandparents until recently. My gratitude and attachment towards my home came directly from the memories I’ve had with my family, especially with my grandparents, not necessarily from how we were gifted the apartment.15

From the first generation, Chimed, who embraced the transition from a nomadic ger to a modern apartment, to Ariungerel, who navigated the tumultuous shift to a new political and economic reality while holding on to the cherished gift of their home, and finally to Temuulen, who now balances the evolving neighborhood with a deep appreciation for her family’s enduring legacy, these apartments stand testament to the resilience, gratitude, and enduring power of home. The family’s experiences testify to the transformative journey of an entire nation. Today, older generations reminisce about life in the Soviet times, while the younger generation embraces changes with an open-minded perspective on the significance of Soviet gifts. These stories remind us that home is not just a place to rest our heads, but holds family history and is a testament to the bond that ties generations together. In a world where everything evolves, these homes remain an anchor to the unwavering spirit of the Mongolian people.

“The treaty between Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR) and Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) for alliance, cooperation and mutual assistance,” News of Ulaanbaatar, January 20, 1966.

Resolution No. 32 of the Executive Administration of the People’s Deputies of Ulaanbaatar, February 13, 1975.

“The first units in the 3rd, 4th microdistrict is now occupied,” News of Ulaanbaatar, November 11, 1978.

“The great microdistrict on the wide-open hill,” News of Ulaanbaatar, January 1, 1981.

Interview with Yanjiv Sodovsambuu, August 22, 2023.

Interview with Dashbal Yunden, October 16, 2023.

Interview with Chimed Damdinsuren, May 9, 2023.

Ibid.

Interview with Ariungerel Chimed, May 16, 2023.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Mayor’s Decree on privatizing apartments, No. A82, May 14, 1997.

Ibid.

Interview with Temuulen Enkhbat, May 20, 2023.

Ibid.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.

Category

Subject

This article was written by Darisuren Azbayar with contributions from Nandin Nyamsuren, Uurtsaikh Sangi, and Temuulen Enkhbat.