And the dandelion does not stop growing, because it is told it is a weed.

The dandelion does not care what others see.

It says, “One day, they’ll be making wishes upon me.”

—B. Atkinson

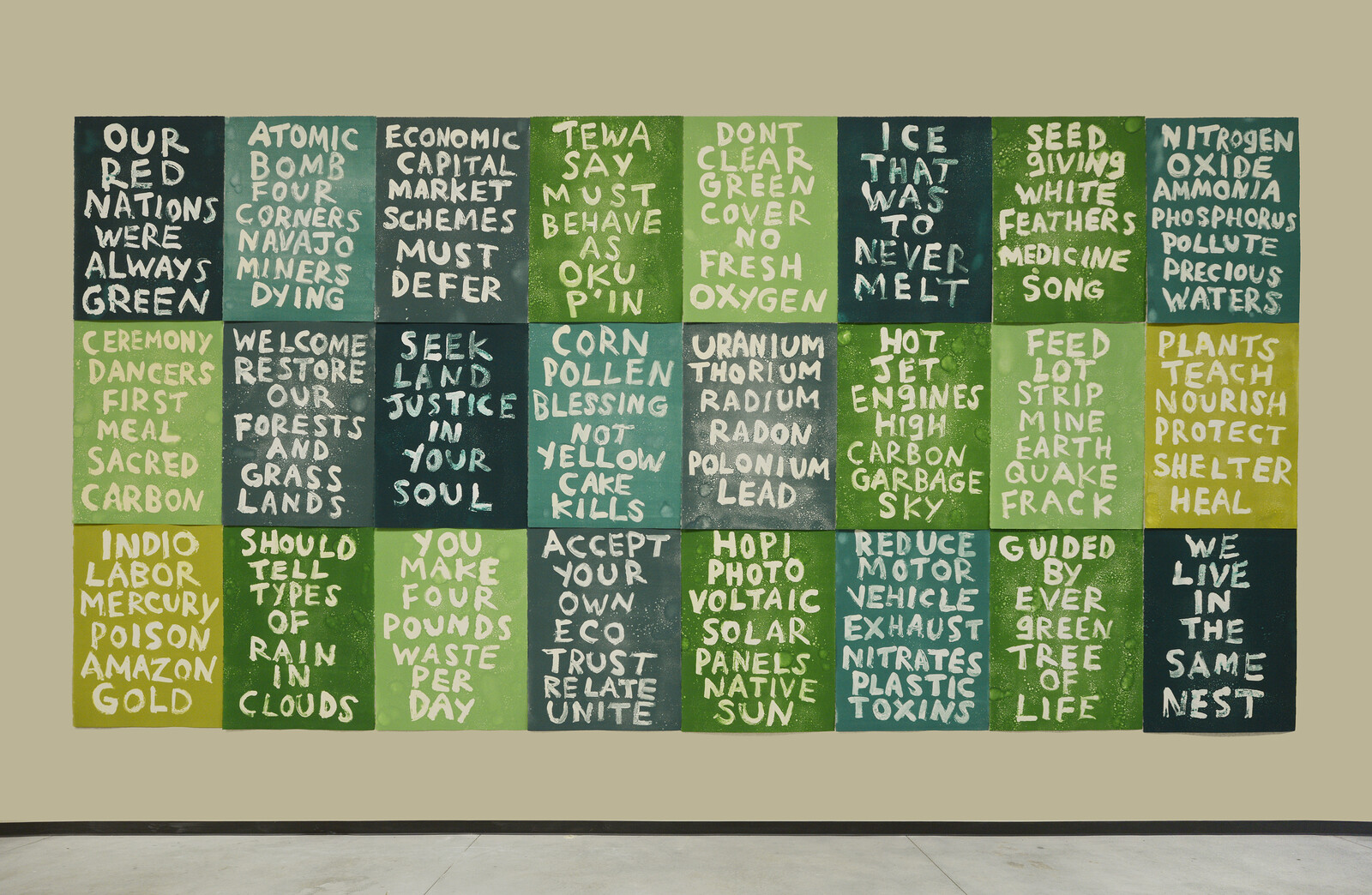

Since time immemorial, the human body has coalesced, entangled, and co-evolved with the vegetal body. One of the very first relationships we ever formed, as humans on Earth, was the one we had—and continue to have—with plants. Plants are the great oxygen-givers of the world, eating sunlight so we can perform that simple yet essential task of life; breathing. They are also the source, directly or indirectly, of all the food we eat, our building materials, the medicines we use to heal, as well as the allies, teachers, guides, and guardians of spirit. To deny we could not survive without the plants would be the demise of our shared humanity.

Yet everywhere we look these days, we see this denial in action. Rippling from this denial are extinction rates higher than have ever been seen before, the widespread application of pesticides and herbicides, the corporate control of seed, water, and energy, the perpetual burning of wildfires, and the spread of zoonotic viral pandemics, just to name a few. The list of cascading socio-ecological concerns is as incessant as it is insistent. This era, we have aptly named the “Anthropocene”—the age of the human. But who, really, is this human we speak of? And indeed, can a human who stands alone, abstracted from our intrinsic relationship with Earth, even be called a human at all? Who are we without the Green Ones? And in the same breath, who are we and who do we become when we lean into the subtle, yet enduring, ways that the Green Ones weave their way through our lives?

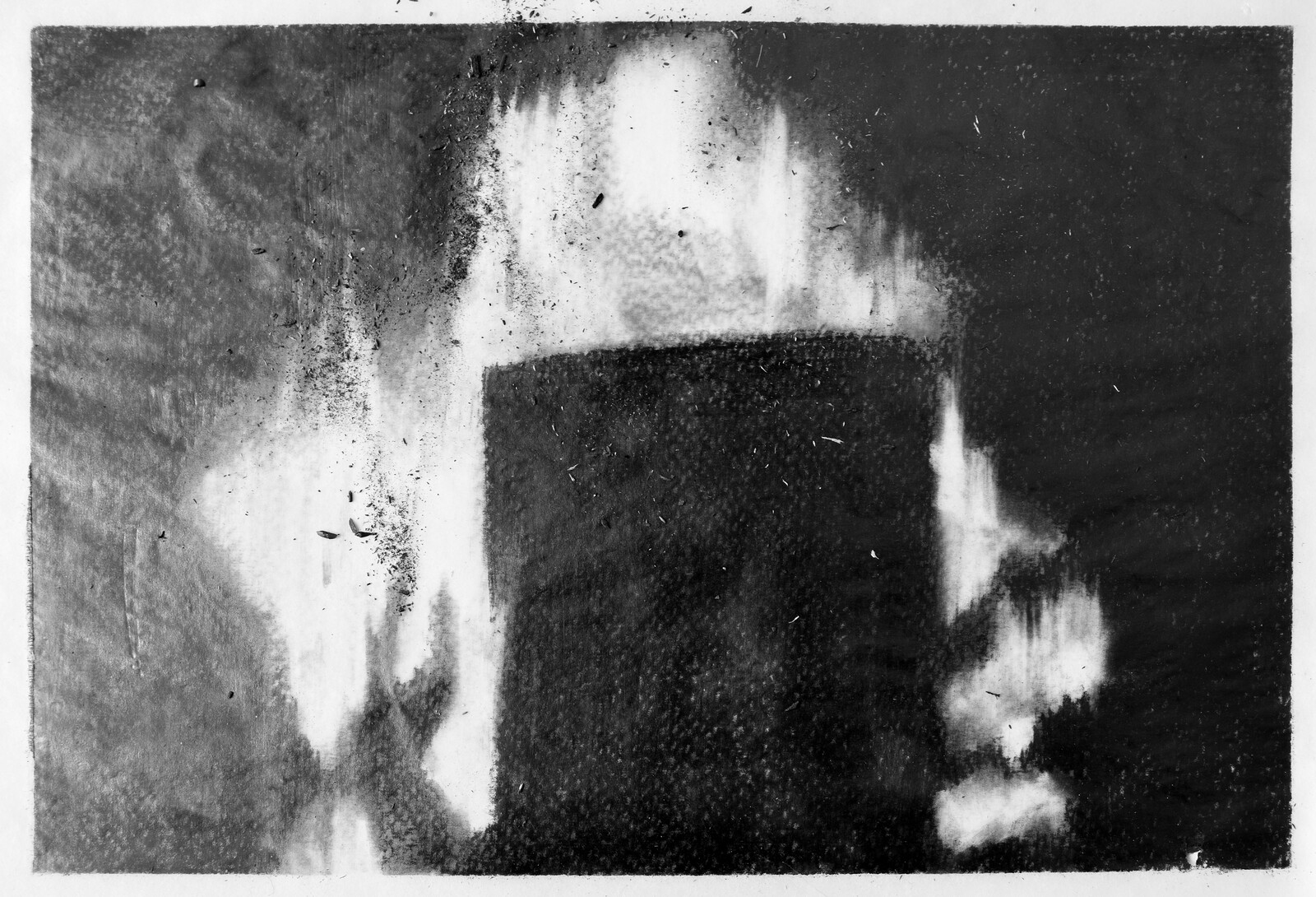

There is an Anishnaabe prophecy of the Seven Fires which essentially tells us, through story, the epochs of human relationship with Earth. Each epoch is elementally articulated through fire, and teaches us, as human people, the value of making wise choices that privilege the ethics of respect, reciprocity, and reverence with Earth. The epoch of the seventh fire puts two options of the journey ahead for humans: one is of a charred, painful path of eternal suffering, and the other describes a soft, green road leading toward a vibrant collective future for humanity. However, the prophecy instructs us that in order to progress down the soft green road, we must turn back to remember and practice the wisdom of all those generations before us. This instruction rests on a deep understanding that the flourishing of life on Earth requires a radical re-orientation toward kinship across all species—vegetal and animal. But what might this re-orientation look like in practice? Active, grounded tending of our relationships with the vegetal may provide some answers. But first, we have to invite other forms of knowing and being onto the scene.

Walking the vegetal path engages both a new and very old thinking and praxis. Yet more often than not, in this modern world, when we think seriously of communing meaningfully with plants, of actual plant-human and human-plant communication, our minds often drift off to idealized virgin forestscapes, where an intrepid anthropologist, lost in the jungle, “discovers” a never-before-encountered tribe and participates in some sort of ritualistic shamanic ceremony. Or perhaps flashes of Stevie Wonder appear in one’s mind, lifted from the 1970s cult classic “The Secret Life of Plants.”1 More often than not, however, the very notion of plant-human communication renders immediate dismissal via an eye-roll or shrug. This is because plants, according to a reductionist and Westernized worldview, are generally seen as a non-agential, non-sentient, backdrop to the central drama of human life on Earth. Plants, it seems, are either not seen at all, or in some cases, seen, but only as an exotic “other.”2

Remembering the meaning of being human on Earth means recognizing that plants are beings of power, influence, knowledge, and wisdom. In recent years, scholars such as Matthew Hall, Natasha Myers, and Jeremy Narby have encouraged and cultivated different and more emotionally rich and respectful ways of living with plants.3 They are prodding us in the West to be not only responsive and responsible for plants’ physical and ecological survival, but also to approach them with increased respect and reverence. When we interact with plants with respect, instead of categorizing them as either desirable or undesirable depending on our own purposes, we can learn to follow the lead of Gilles Clément and envision our world as a “planetary garden,” collapsing the anthropocentric divisions of good and bad, and intentionally collaborating with rather than “managing” against plants and all other nonhuman living beings.4

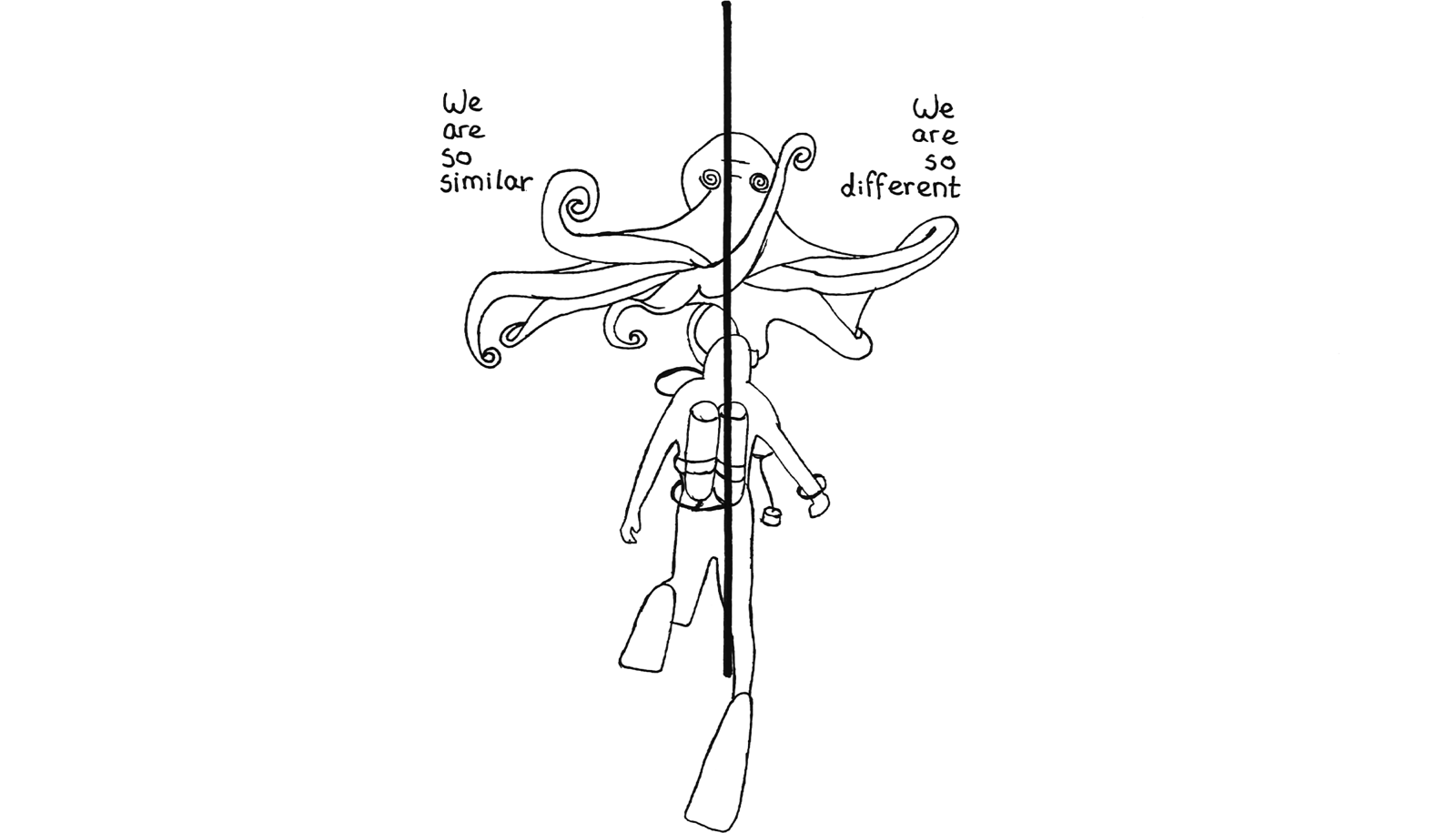

Changing the ways in which we relate to plants is to rethink what both humans and plants really are. This starts with the fact that plants are not inanimate objects, but instead, as told by Indigenous Elders and now shown in more recent scientific research such as that conducted by Daniel Chamovitz, Monica Gagliano, Stefano Mancuso, Suzanne Simard, Anthony Trewavas and others, are sensitive and intelligent beings that have bodies and behavior organized in ways that just happen to be different than for us as animals.5 They move, but just at a much slower pace. They communicate, but often by using a vocabulary of chemical signals that may seem foreign to human senses. They also create sound, but at frequencies humans cannot always hear. Plants, from this perspective, are as much living expressions of consciousness and presence as we humans are, embodying a shared lifeforce that is sustained through relationship. Recognizing this opens up the possibility for re-thinking about the human in a similar way: we think, but not just with our minds; we feel, but not just with our hands; and indeed, we move, but in both overt and subtle ways.

There is also a spiritual dimension to our relationship with plants that has spanned many thousands of years. Whether through receiving visions and lessons through ritual use of plants or by cultivating food and medicine plants, many Indigenous and ecologically-oriented cultures have nurtured a reverence for Spirit through their relationship to plants. Writer and shaman Martin Prechtel speaks to this in his book The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic when he describes the seed as mother of all life; within one seed is the capacity to populate an entire forest, to give life for multitudes in perpetuity.6 Through plants, we are therefore entangled with an invisible thread that connects all that is living, because, quite simply, we are alive and co-evolve in a shared space. When we attune our human senses to the vibrancy of life itself, it is impossible not to feel a sense of mystery and reverence pulsating through all bodies of ecology.

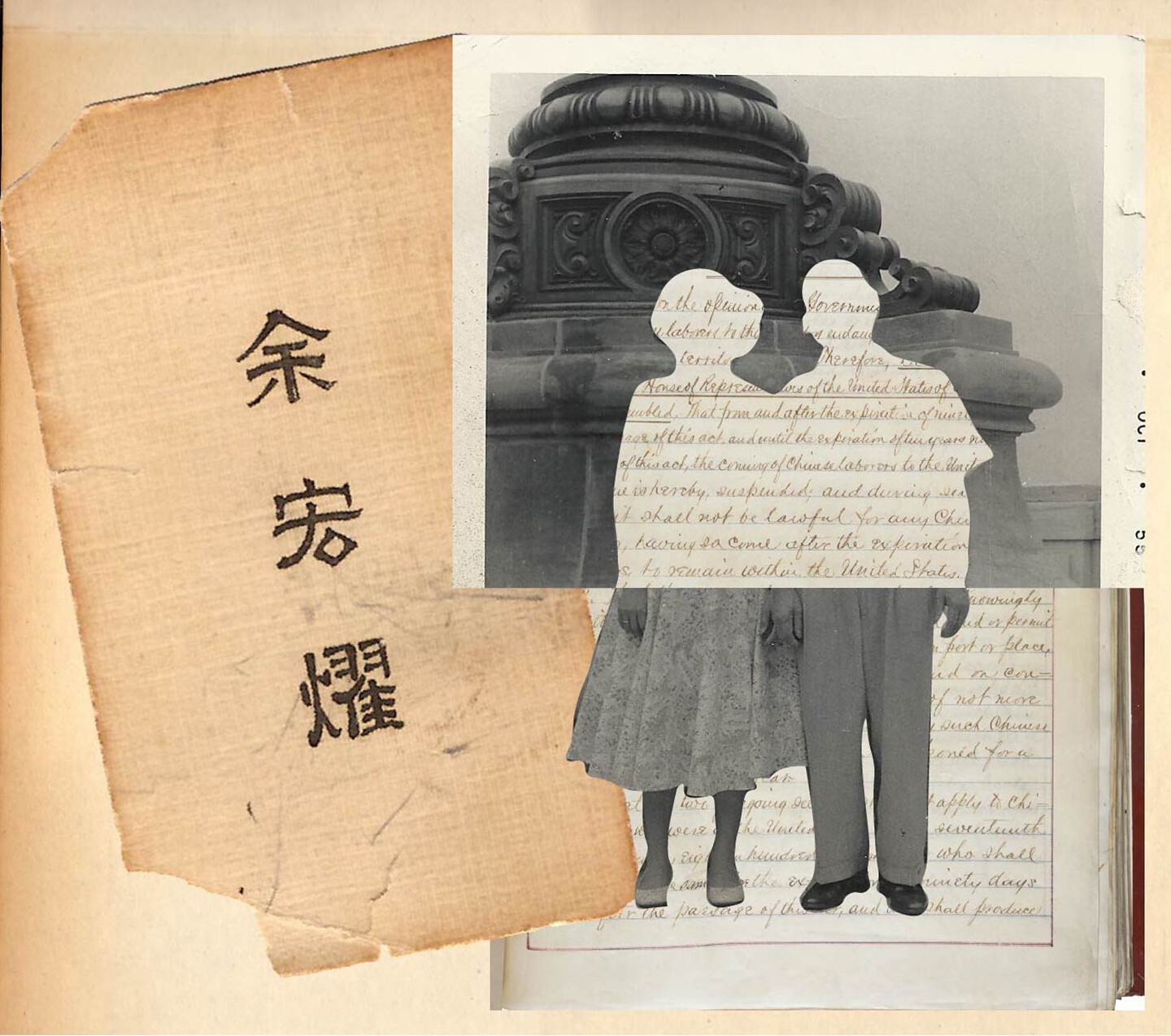

This is inherent to understandings of animism, as discussed by religious studies scholar Graham Harvey.7 While animism carries political baggage and has shapeshifted considerably over the last century of anthropological thought, animism is a grounded and accessible pathway for relating to the more-than-human world in multifaceted, deep ways. This is because, in animist sensibility, everything is conscious and thus capable of reciprocal relationship. Communicating, flourishing, and making kin with plants then becomes not only possible, but embedded as a feature of normal awareness as well as ritualized practice. Moreover, (re)claiming an animist sensibility axiomatically disrupts dominant colonizing reductionist and materialist worldviews and allows not only for radical posthuman kinship, but also enables a simultaneous process of retrospective healing. Animism can lead to a generative composting of the wastes created by colonization that can help nurture more ecologically- oriented, Indigenous worldviews, therefore advancing decolonization of ourselves as well as the Anthropocene.

Anthropologist Jeremy Narby explains in his book The Cosmic Serpent how biochemical and medical knowledge is communicated directly to Amazonian shamans by plants themselves.8 While in Narby’s case, the plants in question are the hallucinogenic brew of psychotropic and purgative plants known most commonly known as Ayahuasca, this phenomenon is not isolated only to psychoactive plant kin. We are all capable of communicating with plants, provided that we begin to, as Natasha Myers eloquently puts it, “vegetalize our sensorium.”9 Rather than limiting the kinds of “knowledge” that can be recognized and transmitted, the quest for knowing and being in this world instead becomes intimately bound as part of a dynamic process; a state that has been articulated by the Vietnamese Buddhist Monk and philosopher Thich Nhat Hanh as “interbeing.”10 That is, because life is in a constant state of relationship, the communication between the vegetal and the human is in and of itself alive and ever-changing, emerging from and contributing to the real and symbolic architecture of those who are doing the relating: human and plant.

Plants can therefore be understood to communicate with humans in a multitude of ways. Ritual, intuitive channeling, song, dreaming, metaphor, and felt sense are but some of the myriad methods through which we can cultivate kinship and embody reciprocal reverence with plants. Think about the old songs held within your own bones. Irrespective of whether or not you are able to create a totally accurate map of your lineage, there are old stories and traditions, one’s that span time and place, that invoke the power of plants to our mythic imagination.11 Plants can help us remember our way home.

For many seasons now, I have watched one companion in particular who we call Dandelion grow not only in the garden, but also in the most unlikely of places throughout (sub)urban landscapes, twisting and turning, feeding on sunlight and thriving in some of the most inhospitable of places. In spring, Dandelion blooms into an expression of sun through a bright yellow flower, reminding human kin of strength through vitality, yet continuing to remain so deeply grounded in the simple act of living. Have you tried digging a Dandelion root out? It is no small feat to keep the whole plant intact. Rather, it remains so steadfast in its connection to source, ready to spread, transform, and tend any broken-ness back to life. The tenacity to guard and tend life above all else suggests a kind of gentle strength, that when mirrored to the human, reveals the inherent capacity to guard and tend life ourselves.

Dandelion shows us how sustenance is held deep within the Earth, and so invites us to extend our own metaphorical roots deeper down into Earth; to root in place and thrive, despite all odds. There is an implicit sense of transferable strength with Dandelion; an embodiment of the Seven Fires Prophecy that we must alchemize the past into the future, opting for depth over distance. Yet somehow, we have waged a war on Dandelion in recent years; relegating Dandelion to the realm of “weed” and therefore an “unwanted” member of our Earth community. The knowledge of our paradoxical relationship flows through me. And so I slow down, I quiet my mind(s), and I observe.

From observation, I turn to action; participating in relationship with Dandelion with all my senses. From an herbalist’s perspective, Dandelion is of particular support to the liver, gently aiding our body’s processing center to filter our human system. As I place a fresh leaf in my mouth, I notice the bitterness as the juices flow across my tongue. Bitter and astringent herbs cause a “drying” sensation, not just in my mouth but throughout my body. I feel lighter almost immediately—not literally in terms of actual weight, but instead figuratively, as if a “weight” has been lifted off my shoulders. What just moved within me in that moment of intimacy with Dandelion?

Dandelion’s capacity to aid in “process” have been known to humans for a long time. In fact, Dandelion was recorded in the mid-fifteenth-century folk/herbal book Les Évangiles des Quenouilles (The Distaff Gospels) as pissenlit, the literal translation from French to mean “piss the bed.” This is thanks to the diuretic quality of dandelion leaves, removing excess “water” from the body and therefore stimulating bile production in the gall bladder. In a similar vein, Dandelion, or Pu Gong Yin, as it is known in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), is a cooling herb and said to temper excess “stomach fires” (gastrointestinal issues) and detoxify the body back into a state of balance.12 Each modality, while appearing divergent in specific applications, all point to a particular essence that Dandelion brings forth: that of cooling, detoxifying, tempering, transmuting. All these qualities are verbs that privilege attention to process over outcome and the inherent strength that emerges through honoring process. In my mind, I hear an incessant chant: “Try as you may, you can’t stop me. I was made to survive.” Suddenly, that metaphorical weight that I felt earlier is rendered real. The psychological and the physical messages entwine in my own instrument of perception—my body—in a perfectly Dandelion-specific way.

Such modes of knowing-with plants are sometimes termed as “intuitive plant medicine.”13 Here, we explicitly bring attention to “intuition” here not to displace the role of intellect, but rather, to trouble conventionally Westernized definitions and expand what is meant by the “mind.” If all bodies of ecology are indeed alive and sentient expressions of Gaia, then it is this very movement of energy through and between these bodies that sustains life itself. This lifeforce can be conceptualized in many different ways—as breath or as spirit—and can be manifested differently for and within each body. Discussing and bringing spirit into the equation is, however, troubling for the modern anthropocentric mind thanks to the self-serving co-option of spirit by institutionalized religion.

In order to take plant-human and human-plant communication seriously, we must challenge and transform anthropocentric framings so that spirit is understood as an inherent and embedded aspect of life itself. This means that spirit does not simply exist intangibly, but can be and is experienced in embodied, material ways, through practice. Spirit, in this sense, is an expression of sentience and relationality, and to take seriously spirit-in-practice is in many ways the practice of tending relationship with a more-than-human world. As Australian eco-philosopher Deborah Bird Rose writes, “to live in a world of sentience is to be surrounded by others who are sentient … in which only some of whom are human.”14 Opening ourselves up to experiencing direct communication and embodied being-with plants is therefore an exercise of extending our preconceived ideas of what a “person” actually means, and then, honing one’s sensorial faculties to stretch our capacity for knowing beyond the human scale and re-connect with what David Abram terms “the many-voiced landscape.”15

Humans are hardwired to engage with plants. The issue here is simply that we, as humans, have been conditioned out of engaging with the vegetal world in an intuitively attentive, multisensorial manner. To re-member this knowing and actively practice these ways of knowing is to participate in the restor(y)ing of the Anthropocene. Like Dandelion, may your taproot burrow so deeply into the Earth that it is near impossible to extract oneself in entirety.

Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird, The Secret Life of Plants (New York: Harper and Roe, 1973).

James H. Wandersee and Elisabeth E. Schussler, “Preventing Plant Blindness,” The American Biology Teacher 61, no. 2 (1999): 82–86.

See: Matthew Hall, Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2011); Natasha Myers, “How to Grow Livable Worlds: Ten Not-So-Easy-Steps,” in The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene, ed. Kerry Oliver-Smith (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2018); Jeremy Narby, “Jeremy Narby: Beyond the Anthropo-Scene,” Bioneers, 2017, ➝.

Gilles Clément, “Favoring The Living Over Form,” PCA-Stream 4, November 2017, ➝.

Daniel Chamovitz, What a Plant Knows: A Field Guide to the Senses (New York: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017); Monica Gagliano, Thus Spoke the Plant: A Remarkable Journey of Groundbreaking Scientific Discoveries and Personal Encounters with Plants (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2018); Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola, Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2018); Suzanne Simard, “How Trees Talk to Each Other,” TED Talk, June 2016, ➝; Anthony Trewavas, “Aspects of Plant Intelligence,” Annals of Botany 92, no. 1 (2003): 1–20.

Martin Prechtel, The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic: The Parallel Lives of People as Plants: Keeping the Seeds Alive (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2012).

Graham Harvey, “We Have Always Been Animists,” YouTube, November 18, 2019, ➝.

Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1999).

Step 7 from Natasha Myers, “How to Grow Liveable Worlds: Ten (not-so-easy) Steps for Life in the Planthroposcene,” ABC Religion & Ethics, January 7, 2021, ➝.

Interbeing is a commonly expressed concept in all the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh and has no singular reference point.

Matthew Hall’s 2020 collection of global botanical myths across time, The Imagination of Plants, is a good starting point for connecting plant sentience with myth and the botanical imagination.

Carl-Hermann Hempen and Toni Fischer, A Materia Medica for Chinese Medicine: Plants, Minerals and Animal Products (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2009).

Pam Montgomery, Plant Spirit Healing: A Guide to Working with Plant Consciousness (Rochester: Bear & Company, 2008).

Deborah Bird Rose, “Val Plumwood’s Philosophical Animism: Attentive Interactions in the Sentient World,” Environmental Humanities 3, no. 1 (2013): 93–109.

David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World (New York: Vintage, 1997).

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.