As I began writing this essay, an opinion piece titled “A Giant Poor Sighted Bird Stands in the Way of India’s Green Goals” from Bloomberg Green pinged my social media radar.1 The article discusses the impact of a recent Supreme Court of India ruling asking for “transmission lines in a large swathe of the region to go underground” on India’s renewable energy targets. The Court’s ruling was in response to a petition to save the Great Indian Bustard, an endangered grassland bird, from “certain extinction” from mortalities caused by flying into power lines. The court ordered the transmission companies to avoid towers in grasslands and instead run the transmission lines under the ground.

After cautioning readers to be aware before taking sides, as the “issue is more nuanced than a straightforward clash pitting industry against nature,” the article’s author argues that “[t]he effort to save the bustard holds risks for what is arguably an even larger environmental cause: It could set back India’s climate goals, which depend heavily on the availability of wasteland like the bustard’s domain for putting up solar panels and wind turbines.” That is a pretty heavy burden to place on the poor bustard’s shoulders.

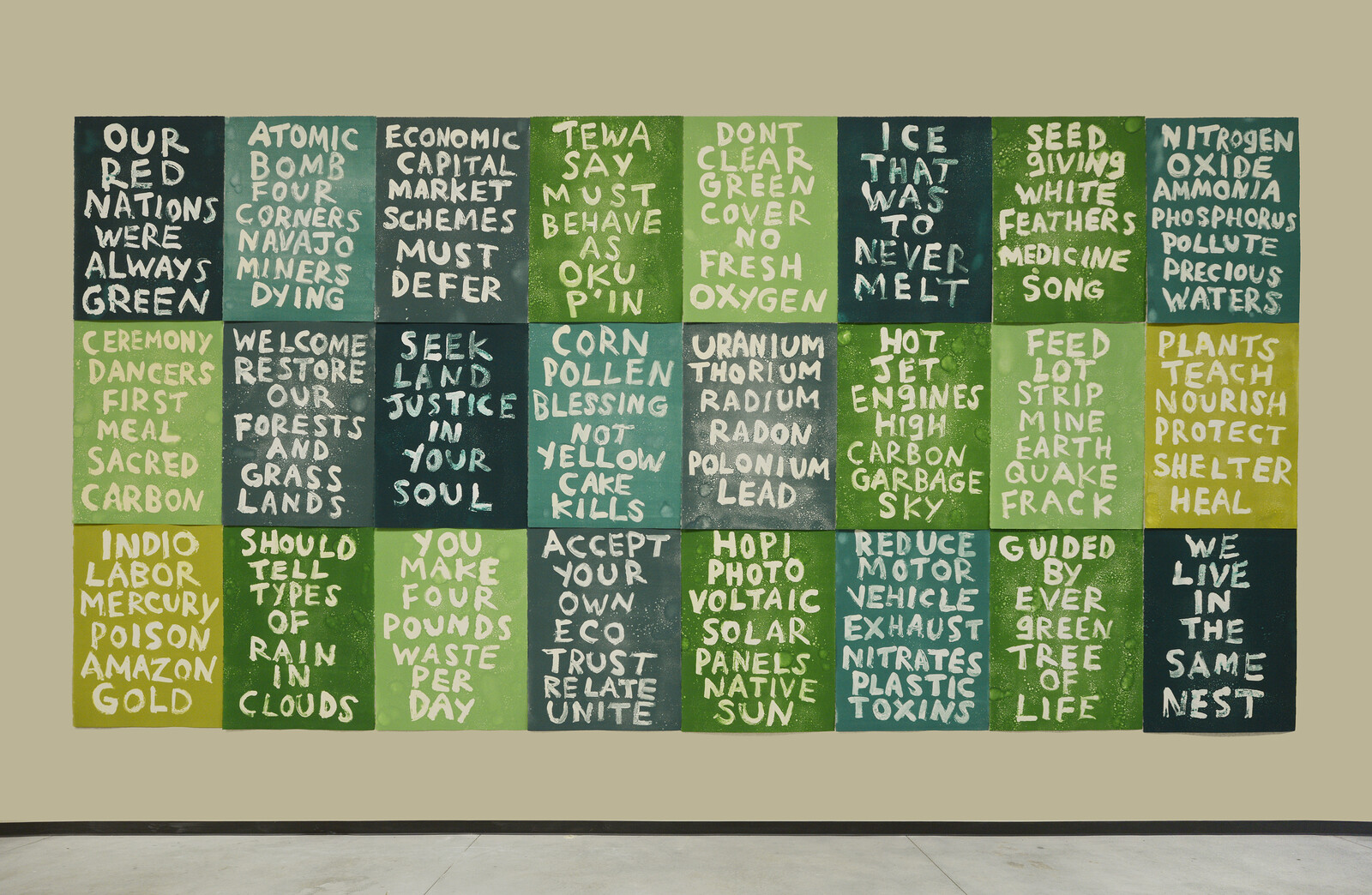

The population of the Great Indian Bustard in India is down to about 150 individuals, thanks largely to the conversion of grasslands for farming and industrial projects. In just ten years, between 2005 and 2015, India lost 31% of its grasslands and 19% of its commons, according to data presented by the Government of India to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification.2 Grasslands were branded as wastelands to justify their conversion in the name of development. Faced with loss of habitat, these gentle avian giants were pushed to the brink of extinction. Now, a “larger environmental cause”—of India meeting its climate goals—is being invoked to set the stage for extinguishing this species and the lands that it calls its home. The bustard’s extinction and sacrificing the grasslands are projected as fair trade for India’s climate goals that involve increasing the share of renewable electricity to power the nation’s notoriously unequal economy.

The bustard won’t go alone. The land it inhabits is a web of interrelationships among and between lifeforms and the non-living environment, each shaping and being molded by the other. Indian grasslands are a commons that support not just wildlife but also a thriving population of pastoralists and farmers. Different estimates place the number of pastoralists at between thirteen and thirty five million just in India that depend on grassy commons for livestock. That is between roughly half and one-and-a-half times the population of Australia. “India meets 53% of its milk and 74% of meat requirement from animals reared by pastoralists.”3

Wasted Sunshine

In the semi-arid karisal (black clay) lands of Kamuthi in Ramanathapuram district of Tamil Nadu, Adani Green Energy operates a 648-megawatt solar photovoltaic project. Ironically, Adani’s sister company in Australia is pushing to operate the world’s largest coal mine in the face of stiff opposition from environmental NGOs and local aboriginal people. In Kamuthi, Adani’s project with 2.5 million solar modules is spread over around 3,000 acres—the size of 1,500 soccer fields.4

Ramanathapuram is famed for its centuries-old kanmais (irrigation tanks) that trap water and extend the farming period in this dry, but fertile land. The meikal poromboke (grazing commons), tank beds, and even private farm lands support a thriving livestock economy, specializing in hardy native sheep and goat breeds. According to Seeman Thangaraj, a breeder of native bulls and goats from the nearby city of Madurai, “Farmers allow, even pay for, goats to graze on private lands because they fertilize the fields with their droppings. The fallow lands and the kanmai edges have enough fodder.”5

The photovoltaic power station encloses three kanmais and deprives locals of more than 3,000 acres of grazing land. The solar panels are arrayed covering the entire catchment of the kanmais. Global green energy cheerleaders claim that solar power stations like the one in Kamuthi are generators of clean, sustainable energy. But this claim assumes that the land is dead. It hides the energy cycles that are disrupted when 2.5 million panels intercept the sun’s rays, preventing them from striking the ground. Solar energy harvested by vegetation satisfies the fuel, fodder, and livelihood needs of local communities and other life-forms. Managed well, these services can continue indefinitely to support the modest lifestyles of local communities. In contrast, Adani’s project—owned by one of the wealthiest billionaires in India—has a lifespan of about twenty-five years. It hurts local communities, robs non-human life of their refugia, and enriches a prosperous corporation.

Viewing the global ecological crisis solely through a climate lens is fraught with false solutions and spurious dilemmas such as this. This is not surprising. Climate discourse is embedded within a status quo-ist framework, and comes with an unhealthy preoccupation with excess CO₂ in the atmosphere to the exclusion of all other drivers of ecological collapse. With eyes turned skywards, it is easy to lose sight of the multiple causes of our planetary disease which are all rooted in land, and what transpires on it in the name of development.

Blame it on Climate Change

On December 3, 2015, as world leaders gathered in Paris for the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (COP21), the south Indian coastal city of Chennai was grabbing international headlines as the latest reminder that climate change is real. Two earlier bouts of heavy rains in November had submerged parts of the city, including the famed IT corridor that serviced global businesses. The rains of December 1 and 2 drowned all of it.

The crippling Chennai floods were blamed on climate change. I wrote at the time that it was, instead, the fault of short-sighted engineering interventions and land-use change, specifically the conversion of fragile wetlands into real estate, that had caused the floods.6 Four years later, Chennai once again made headlines. This time, it had “run out of water.” Once again, international media looked for climate angles to frame this crisis.

While climate change is sure to play an increasingly significant role in worsening the problem in coming years, it has little to do with the city’s current predicament. Chennai’s vulnerability to both floods and droughts is historical folly rooted in destructive land-use changes and its drive to pave over its wetlands in the name of growth. Between 1980 and 2010, the built area of the city increased from 47 to 402 square kilometers, while wetlands decreased from 186 to 71 square kilometers.7 In successive waves of urbanization and industrialization, wetlands, grazing commons, and even waterways were repurposed as residential layouts, industrial estates, and urban infrastructure.

Before the British East India Company set foot on this part of the coast, the region was a vast patchwork of agrarian settlements bound on the east by a long stretch of sandy beaches. The monotony of the beaches was broken by mangrove-studded estuaries formed by seasonal streams and rivers that drained these lands. The flat terrain was not amenable to retaining water except in the sprawling Pallikaranai marshlands in what is now the southern part of the city, and the much larger tidal wetlands of the Ennore-Pulicat region to the north. To make water stay and enable agriculture, medieval engineers carved out gravity fed irrigation tanks called eri, and drinking water bodies called ooranis and kulams. Settlements were built upgradient of the eris and agriculture and grazing grounds were located downgradient. Eris not only had their own catchments, they also received water through specially designed inlet canals from upstream tanks. They then discharged their surplus through canals that filled other eris downstream as they cascaded down to the rivers and the sea.

The urbanization that began with the arrival of the British in 1639 valued buildable land that could serve the purposes of colonial extraction and urban expansion over everything else. Water, the one element for which earlier agrarian cultures transformed the landscape, began to be viewed as a nuisance and a health hazard inside the city. This was used as a justification to pave them over and develop them as real estate. What the British colonial government began, the state-level administration in independent India continued with added vigor. The result is an urban sprawl that converts natural events like heavy rainfall and seasonal droughts into national disasters. This will only get worse with climate change. But what ails the city, and indeed the planet, is not merely excess carbon in the air, but what has been done to the land, particularly the commons, and the people dependent on it, in the name of development.

The Battle for the Poromboke

Poromboke is a Tamil revenue category of medieval agrarian origin that denotes lands set aside as commons for the shared use by communities. These lands posed a curious challenge to Britain’s obsession with turning land into property and roping them into the colonial project of yielding value to the economy back home. Poromboke commons were governed by two rules: they could not be purchased or sold as they were communally held, and they could not be built upon. These lands were untaxed and yielded no revenue to the crown.

From a capitalist perspective obsessed with private property and the act of building, digging and paving, the poromboke commons were worthless. It is no coincidence, then, that the entry of the British into Tamil Nadu signaled the erosion of the meaning of the word poromboke. In contemporary colloquial Tamil, the word has degraded in meaning to a pejorative, used to refer to worthless people or wastelands. The term wastelands, used in the Bloomberg article to describe the bustard’s habitat and the pastoralist’s grazing grounds, was and continues to be used as a weapon to devalorize the commons and dispossess its human and non-human users. The making of the city of Chennai, and its continued growth, is an ongoing history of such enclosures and erasures.

Enclosing the poromboke commons is not an easy task. These lands support livelihoods of artisans, fishers, farmers, grazers, and gatherers; they are sources of water, fuel, fodder, and medicine. For a landscape dismissed as wastelands by the dominant elite, these lands are all that stand between life and death for millions of India’s poor. Alienation of the poromboke has triggered potent conflicts with communities that value the commons. Legally, too, poromboke lands remain unbuildable and out of bounds of the property regime.

However, such legally protected lands continue to be encroached upon despite community opposition. Chennai’s tryst with floods and water scarcity is the consequence of a battle of values where the poromboke has lost to the urban project. But the fight for the poromboke is far from over.

The Song for Chennai’s Poromboke

On Chennai’s northern edge, the sprawling tidal wetlands of Ennore, formed at the Kotrallai River’s confluence with the sea, have faced devastation since the 1960s by an onslaught of industrial projects including power plants, coal yards, refineries, and coal ports. Riverbeds have become choked with coal ash, estuarine waters slick with oily effluents from the refineries, and tidal backwaters lost to port infrastructure. The damage to the life-giving waters of the river have put the region’s fisherfolk on a collision course with industrialization. But despite the intensity of fossil-fuel-centered development in Ennore, the fight of fishers for environmental justice has never been about climate change. Rather, it has been about their equal right to a healthy environment and a dignified livelihood.

The struggles of the fishers had remained invisible until a larger campaign called “Save Ennore Creek” brought them into partnership with activists from other parts of Chennai. This strategic collaboration embedded their efforts in wider struggles over ecological values, the meaning of “development,” and disaster and public health risk for the larger region.

The 2015 floods offered an opportunity to revalorize the abused and marginalized poromboke. In 2017, Kaber Vasuki, a talented young songwriter transformed a little-read journal article I wrote the year earlier article into lyrics for a Tamil song. Rendered in the karnatik genre by T. M. Krishna, a renowned musician and activist, and shot as a music video in the dystopic waterscapes of the Ennore wetlands, the “Chennai Poromboke Paadal” (“Song for the Chennai Poromboke”) took a swinging punch at the popular notion of development and its perverted metrics to measure the worth of the commons.

Choosing social media as a forum to assert the importance of poromboke rather than approach the courts to assert their legal status was intentional. The word has denigrated in the cultural register; a cultural intervention is necessary to revalorize the notion of open, unbuilt, and unenclosed commons. For legal status to matter, culture has to change.

The choice of the musical style was intentional too. Karnatik is an elitist genre with a self-professed air of refinement and discipline, and claims to engage with the profound. Where the karnatik is associated with the upper caste, the poromboke is of the masses and the working castes. If karnatik represents purity and the divine, the poromboke deals with the mundane and shuns the discrimination inherent in advancing notions of “purity.”

In May 2021, dictating an order against the hand-over of hills and hillocks for mining, Justice G. R. Swaminathan of the Madras High Court observed: “A judge must exhibit awareness of what is going on. His inner antenna should catch signals. To create such an ambience, before dictating this judgment, I listened to T. M. Krishna’s ‘Poramboke Paadal.’” 8

Let Chennai Breathe

In a widely read article from 2021 titled “The Climate Crisis is a Crime Story,” Mark Hertsgaard writes that “Every person on Earth today is living in a crime scene… The crime in question is the fossil fuel industry’s 40 years of lying about climate change.”9 Hertsgaard’s claim suggests that we all are equal victims of the same crime, that we confront the same criminal— big oil—and share a common future. The truth is that we don’t. Frontline communities of fishers, farmers, and indigenous communities have borne the brunt of harm due to environmental degradation. The world’s elite began their fight against fossil fuel only after climate change became real to them, personally. Even now, climate discourse is dominated by calls to keep coal and oil in the ground and switch to renewables.

But well before fossil fuel became the villain of the climate movement, frontline communities in India of indigenous people, dalits, fishers, and other subordinate classes were already fighting solitary battles against mining, hydrocarbon extraction, air pollution from industries and automobiles, and the mindless destruction caused by the over-consumptive modern economy. They did this not because oil and coal damaged the climate, but because it harmed the land they lived with, and because they resented the discrimination inherent in apportioning costs and benefits.

The stretch between Ennore and Manali in North Chennai is home to two coal power plants, coal stackyards, coal ash dykes, the state’s largest petroleum refinery, and a mega petrochemical industrial estate. This predominantly working-class region is the real crime scene. Where south and central Chennai are showcased by the state to lay claim to world-class status, north Chennai is a fetid cesspool of industrial badlands, targeted by the state for increasing toxic industrialization. The ongoing and increasing pollution here is not merely incidental; it is a modern and environmental expression of casteism.

R. L. Srinivasan is a fisherman from Kattukuppam, and a kabaddi coach, a traditional Indian contact sport. Played between two teams on a court with two halves, the game involves a raider taking a deep breath, running into the opposite team’s court, and tagging as many people as possible without being tackled or losing one’s breath. The game involves stamina, agility, and strength, qualities that Srinivasan says are scarce among this generation of youngsters from the region.

“They can’t hold their breath for long. The pollution has compromised their stamina,” he says ruefully. Srinivasan’s two sons are kabaddi players, but “they’re not as good as we were. Overall, they are weaker.”10 North Chennai has been a wellspring of athletes and sportspersons, but there are hardly any open spaces today, let alone playgrounds that do not have smokestacks and flare towers looming ominously over them.

In January 2020, Justice Rocks—a city-based anti-corporate initiative that deploys art for activism—collaborated with youth-led Chennai Climate Action Group and youngsters from North Chennai to release a Tamil English rap video featuring out-of-breath kabaddi players and calling for a timebound plan to clean-up North Chennai’s air. Shot amidst smoking chimney stacks in the poisoned playgrounds of North Chennai, “காத்த வர விடு: Let Chennai Breathe” is a reminder that the need to save the present has been ignored for far too long.

Conclusion

Motivated by the fear of cataclysm, climate discourse tends to be futuristic and ahistorical. Meanwhile, communities engaged in environmental justice conflicts are fighting to spotlight their oppressed pasts and improve the present as a necessary pre-condition to securing their futures. Their fights are not restricted to fossil fuel projects, but extend to all land-degrading, resource-alienating activities required to keep the growth-centered economy growing. Such community responses assert the ideal of equality and resistance against the erasure of the plural narratives around land.

The brand of activism that follows when climate change is used as a frame is prone to maintaining the status quo of social relations, and even paving the way for democracy to be suspended so that technological interventions can take center stage as solutions. Responding to floods by building stormwater drains, to water scarcity by constructing desalination plants, or to climate change by posing large-scale renewable energy projects as an alternative fuel to power an inherently unsustainable and unjust economic system exposes a reductionist approach that is content with picking low-hanging fruit. Such a “solutions culture” relies on perverting democratic processes and externalizing actual costs to under-represented populations of marginalized communities, non-human life, and unborn generations.

Environmental justice struggles are inherently counter-hegemonic, and cannot succeed without inverting existing power relations and challenging the patriarchy. At the same time, such struggles inevitably yield climate dividends. The metrics of climate action are amenable to the convenience of big capital, and not designed to challenge inequality. Success in this framework is premised on keeping the wheels of consumption turning on greased axles, and is prone to calling for a postponement of social justice concerns in the name of urgency.

Even environmentally, climate action is unlikely to succeed as long as it is wedded to growth. And growth cannot be tackled without addressing social injustice. Green growth and Green New Deals are premised on a notion that technological change will enable sustained economic expansion by decoupling GDP growth from resource use and carbon emissions. Jason Hickel and Giorgos Kallis debunk these claims, arguing that “[t]here is no empirical evidence that absolute decoupling from resource use can be achieved on a global scale against a background of continued growth.” 11 Even if it did, however, there is no evidence that such growth will rearrange society to be more equitable. As Chico Mendes aptly put it: “Environmentalism without class struggle is gardening.”

Rajesh Kumar Singh, ”The Great Indian Bustard And India’s Renewable Energy Challenge,” All India/Bloomberg, June 16, 2021, ➝.

Kiran Pandey, “India lost 31% of grasslands in a decade,” Down To Earth, September 10, 2019, ➝.

Jitendra, “Recognize environmental contribution of pastoralists: Experts,” Down To Earth, October 3, 2019, ➝.

“Adani Unveils The Worlds Largest Solar Power Plant In Tamil Nadu,” Adani Power, September 21, 2016, ➝.

Interview with author, August 2020.

Nityanand Jayaraman, “Why engineering interventions won’t prevent another flood in Chennai,” Scroll.in, September 7, 2016, ➝.

Study by Care Earth, cited in Prabhash K. Dutta, “Why Chennai will keep choking, drowning with every spell of heavy rains,” India Today, November 4, 2017, ➝.

Bar and Bench (@barandbench), “The judge Justice GR Swaminathan noted that before dictating his judgement he listened to ‘puramboke paadal’ by @tmkrishna,” Tweet, May 30, 2021, ➝.

Mark Hertsgaard, “The Climate Crisis Is a Crime Story,” The Nation, June 30, 2021, ➝.

Interview with author, August 2016.

Jason Hickel and Giorgos Kallis, “Is Green Growth Possible?” New Political Economy 25, no. 4 (2020): 469–486, ➝.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.