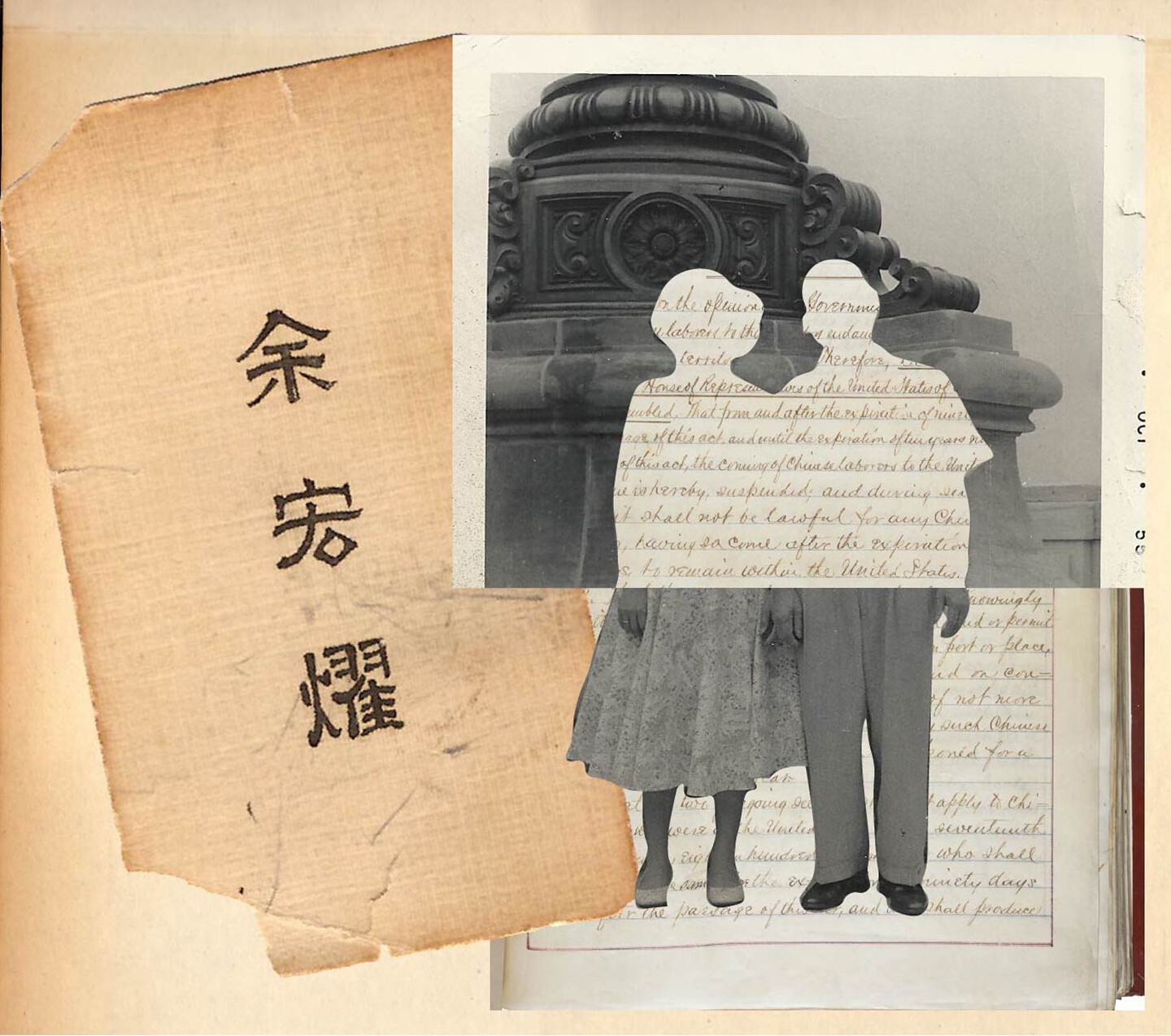

The word nostalgia derives from a sickness of home, from the trauma and longing one feels after being artificially and involuntarily ripped from your environment. Originally classified as a disease, by the 1830s, the word was used to describe any “intense homesickness: that of sailors, convicts, African slaves.”1 The word’s etymology is intimately tied to experiences of displacement, of being pushed out or torn away from a place where one’s memories and emotions are resonant and rooted in a specific proximity of locality and time.

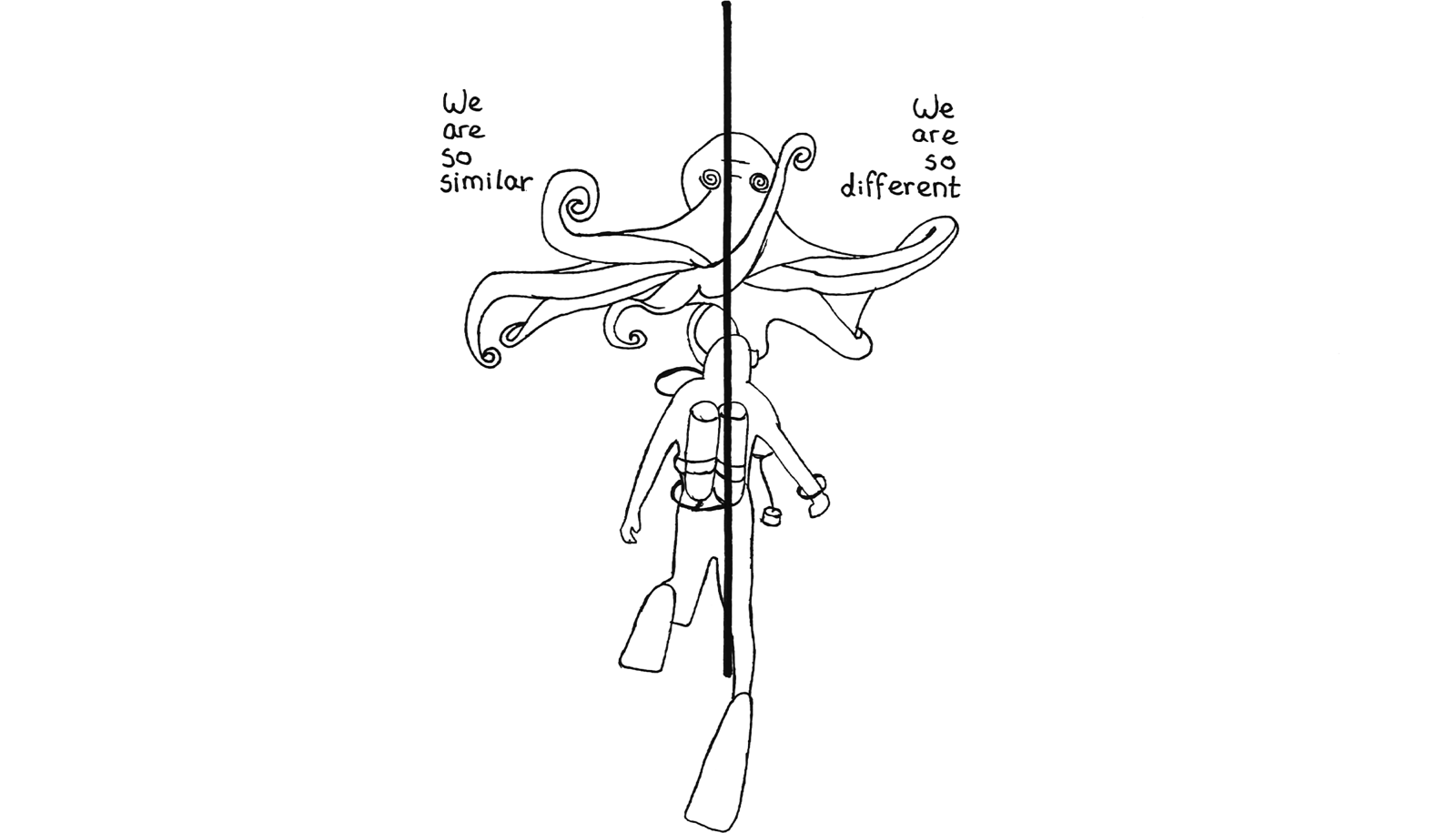

The nature of nostalgia is a window into an understanding of the concept of time and memory. Memory shows us that time is not absolute, and that subjective, temporal experiences often dominate mechanical, linear, objectified understandings of time. Memories are crystallized into our own private space-times, ones primarily informed by our personal perspectives and experiences. Memory’s flexibility and fluidity between our interior lives and our exterior realities, and its ability to be invoked by our encounters with particular objects, locations, sounds, images, and smells accounts for the fundamentally different but interconnected and often entangled experiences, temporalities, and memories between people, communities, and cultures.

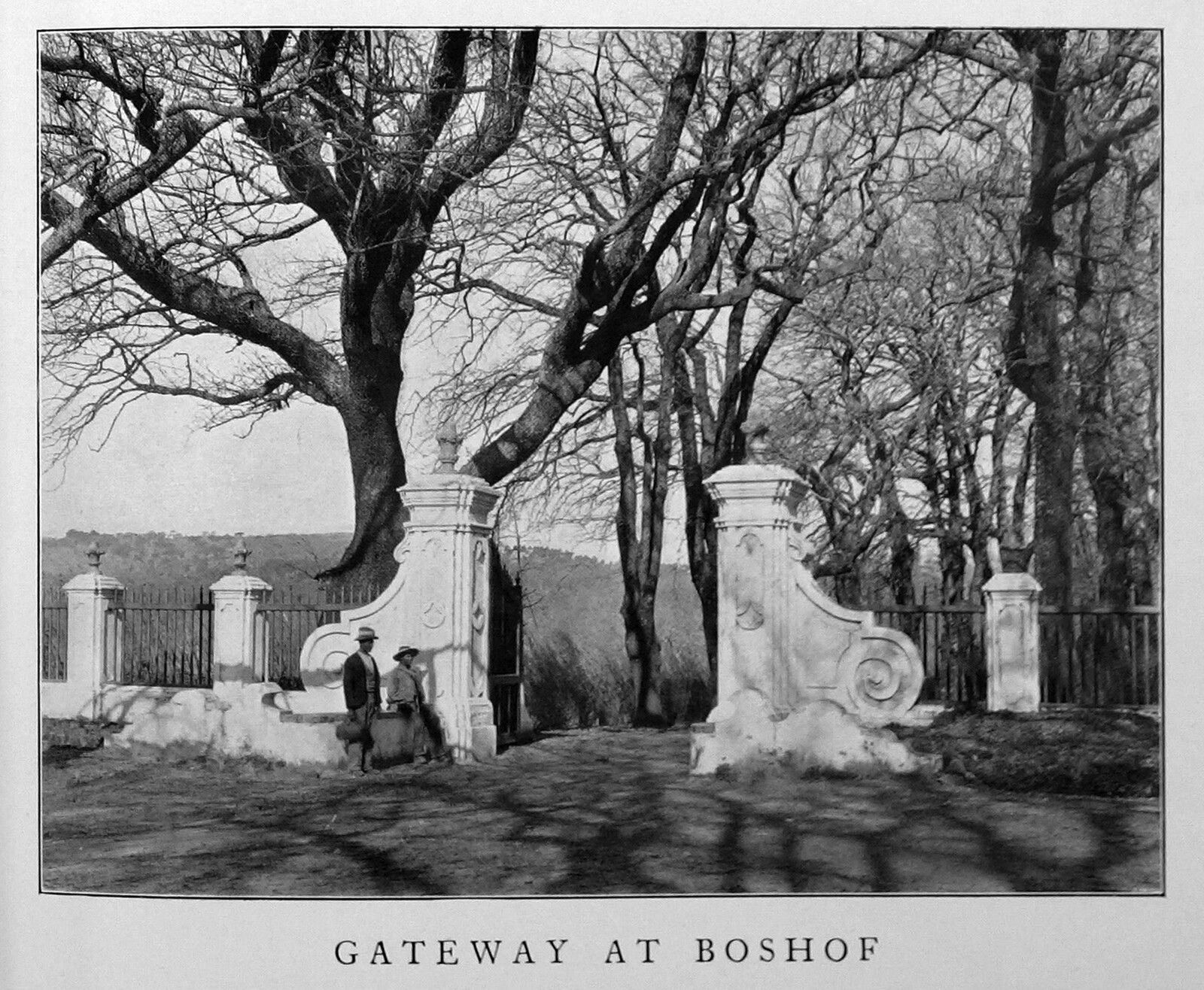

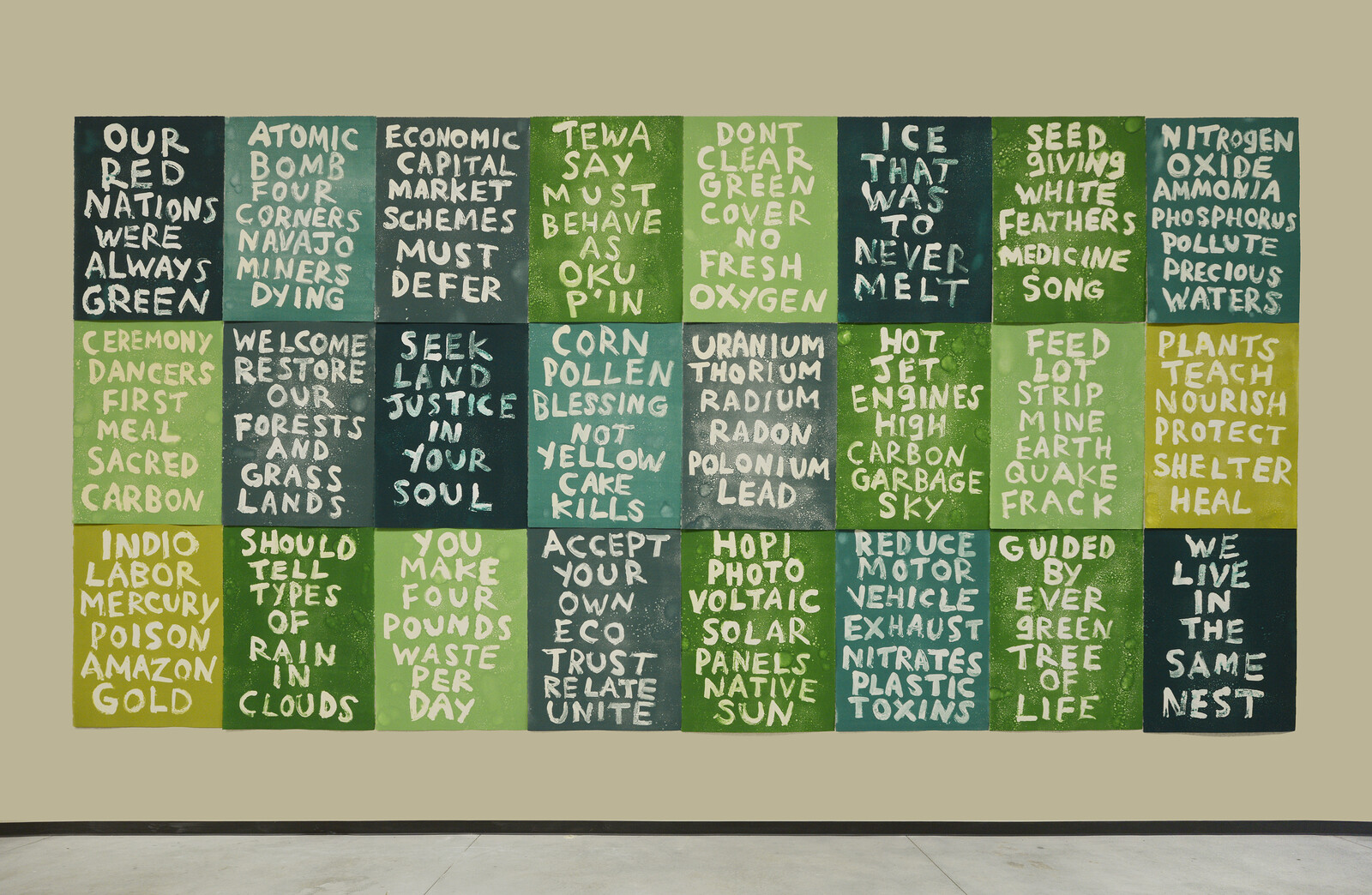

Time, experience, and episodic memory is wound up in the places we call home, wrapped around the objects that inhabit them, and embedded in the land itself. It is only our so-called failure to accelerate quickly enough on the progressive, capitalist timeline and arrive to the futures envisioned by the state that produces nostalgia. This so-called failure is also what keeps marginalized Black and Brown people locked into a narrow temporal present(s), bereft of tools, disconnected from resources, with limited and inequitable access to time, memory, and rooted location.

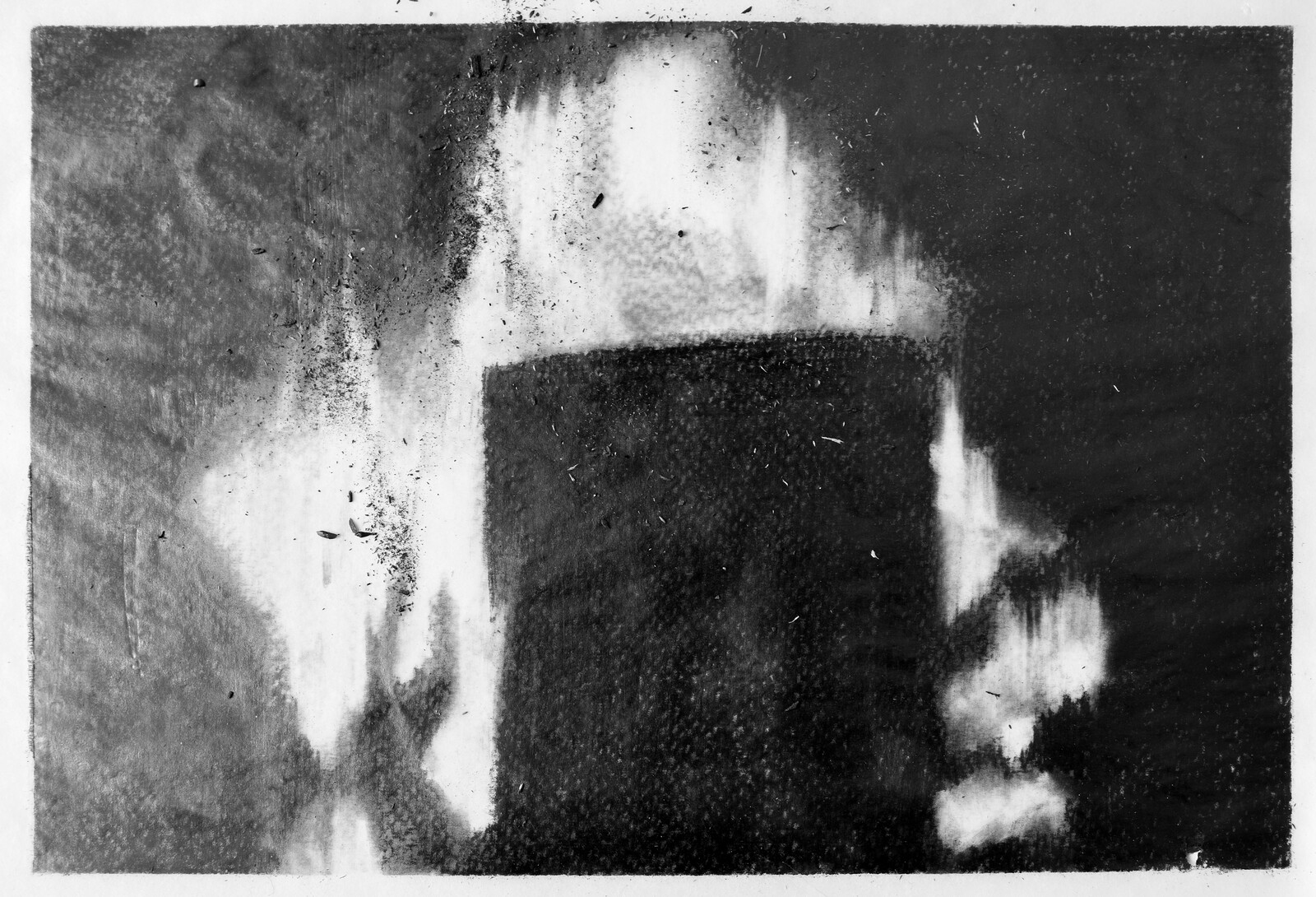

And yet, even in the face of forced nostalgia, we find resistance through remembrance and ever-expansive timescapes that disrupt the timeline, or otherwise hack it to ensure our survivance into the future(s), as well as our appearances in the past(s). Through the recovery and binding of ancient and new Afrodiasporan tools, resources, and technologies, we can construct portals, time capsules, and temporal displacement devices that help us define, find, create, escape, and/or return home.

Such portals contain visions, rhythms, textures, artifacts, and temporalities constructed from the dance of intertwining strands of ancestral, maternal, communal, and personal memory. We find ourselves in the now-here due to the daily rituals of our great grandmothers and mothers, where they created time, space, and home from nothing—a feat as simultaneously mundane and crucial as the Big Bang. These are everyday miracles of life as we know it, and they should not only be summoned, but honored.

Douglas Harper, “Nostalgia,” Online Etymology Dictionary, 2021, ➝.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.