In the mid-1980s, I was looking for a place to live and photograph.1 A place to lean into, to know in an intimate way. For years, I had been inspired by Henry David Thoreau’s journals. He had the ability to draw epiphanies out of the most seemingly ordinary observations, epiphanies that still resonate today. On a chance visit to the modest coastline of New Hampshire, I knew immediately I had found my Walden by the sea. It is not a dramatic coast in the way Maine can be, but its rough, raw, primal rocks meet the wide sweep of the Atlantic with equal courage. Fortunately, this elemental world starts just twenty feet from any of the numerous turn outs up and down the coast road: a crucial practicality for a photographer lifting a heavy 8x10 view camera with film and lenses. I felt blessed. Soon, an unclaimed two-mile stretch of coastline became my studio, my partner, my place of contemplation and refuge. Slowly, without my noticing, an alchemy began between us. Most days we were left completely alone in this liminal zone. As far as I could see, with the exception of a few summer months, very few people cared much about the coast.

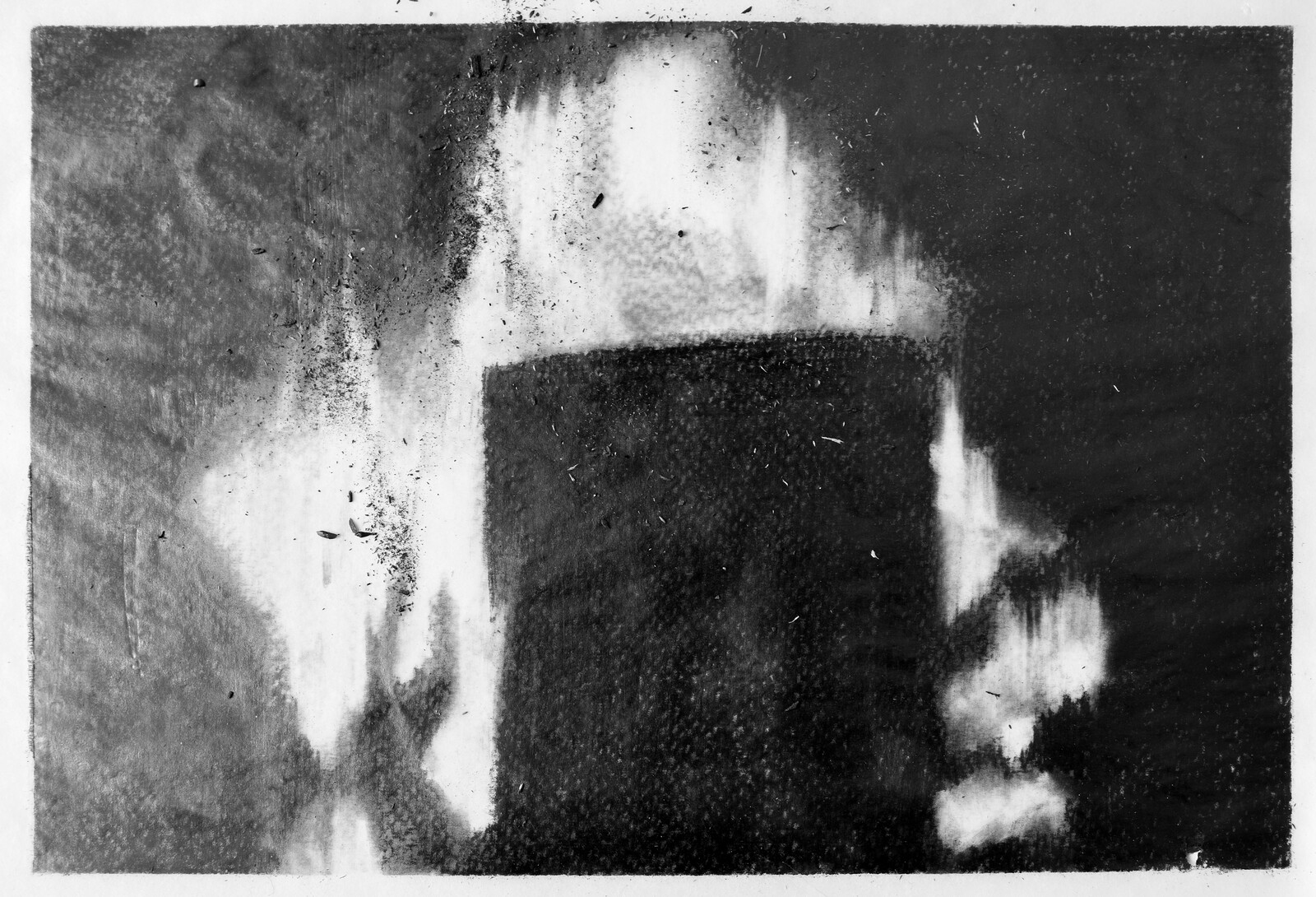

Stones and rocks have always carried a special fascination for me, but I had never lived where they were such a prominent force in the life of the land and sea. Eons of storms and tides are the chisels of infinitely creative fractures and re-fractures. Over the years, I found myself called to individual stones. They seemed to exude a palpable numinous quality. They felt like heavy, textured pools of silence holding a visceral stillness that resonated with some silent awareness within me. There was a sense of shared recognition which deepened my confidence in our connection. I soon began bringing them to my studio in an attempt to photograph them individually or in groupings. Their felt yet unseen presence started to become the real subject of my photographs. But somehow, no matter the long hours of effort, this ineffable dimension often remained elusive in the final images. These subtle realms required a finesse I had yet to trust.

I sensed I was encountering a dimension of the natural world, and stones in particular, that I was unprepared for. Each new stone came with a sense of urgency as if it were a new insight drawing me closer to something. I had experienced this heightened sense of aliveness and presence before, at certain times in certain landscapes, but somehow this was more focused, more specific. It felt inexplicably personal, intimate. Some part of me watched myself be brought to tears if a stone I was carrying carelessly slipped from my hands falling to the rocks below, chipping or breaking. Why such a reaction? How could I care so much? Some stones seemed like miracles of improvisational lithic calligraphy or hieroglyphs asking to be acknowledged. It was as if I was struggling to remember a language I once knew. All I could do was look in grateful, uncomprehending awe. And yet I also knew these were common stones easily overlooked amidst fields of countless similar rocks.

This went on for almost fifteen years. All the while, I was coming to know and to be known by a palpable presence in the land. I knew that sculptors like Brâncuși and Noguchi shared these sensitivities for the inner life of stones, but the only place I found actual information was in books about the shamanic beliefs and practices of indigenous cultures. I read inspiring yet seemingly fantastic accounts about the magical qualities of stone, but it seemed unlikely I would ever be able to meet these people whose vision of reality was unconstrained by the accepted norms of Western rationality.

And then one day, in a moment, all that changed. In a seemingly chance encounter on the street with a woman I barely knew, I was told about a remote tribe of Indians living high in the Andes of Peru who “worked with stones.”

Q’ero

The Q’ero are often called “The Last of the Incas.” They live in six small villages at altitudes of 13,000 to 16,000 feet. Each village is a cluster of simple stone houses with thatched roofs nestled into mountainsides next to fresh water streams. They are connected by the ancient footpaths worn into the land by the feet of their ancestors. All over South America they are held in special reverence for the purity of their traditional wisdom. Their natural isolation has allowed them to preserve ancient ways of knowing from the influence of outsiders, especially that of the modern West. They were first “discovered” by the outside world in 1949 when an anthropologist from Cusco noticed their unique dress and demeanor at a huge annual festival they came to partake in. However, the first expedition to the land of the Q’ero was not until 1954.

When I arrived in the spring of 1998, the centuries-old traditional ways were still intact. Our expedition was led by Juan Nuñez del Prado, the son of the anthropologist who first contacted the Q’ero. After an eight-hour drive from Cusco on rough and dusty mountain roads, we camped for the night in a small village where the road came to an end. In the morning, after a short breathless soccer game with the local children, we began our nine-hour horseback ride. Rocky narrow paths clinging to the steep canyon walls led toward the high mountain passes that would eventually bring us into the homeland of the Q’ero. By twilight we were leading our horses through a sharp rock crevice that opened to a broad valley below. The snowstorm that had greeted us when we crested the continental divide just earlier made the footing treacherous for both our horses and ourselves. To my right I caught sight of three women in traditional woven bright skirts and hats running in open sandals to gather in the llamas for the evening. Through the dimming light and the white of snow we could just make out the ancient village of Chua Chua below. I was wet and cold and disoriented by the crush of altitude. Only later did I realize that each step down that last snow-covered hillside was drawing us more deeply into a world whose primordial heart was still beating to the rhythms of an ancestral way of knowing.

Chua Chua

As I crawled out of my tent early that first morning in Chua Chua and breathed in the thin mountain air, the otherness of this world before me began to be revealed. The overnight snow had cleared and a gentle stillness filled the valley. The thatched stone houses and our sagging tents were covered in eight inches of snow. The sky was a high-altitude predawn blue. The air and the silence were crystalline. To warm myself I began walking as the first rays of the sun illuminated the tops of the surrounding mountains. I found a stone to sit on and watched as the day brightened. Not far away a little rushing river ran through the center of the village. There was stirring in the mess tent, the bells of the llamas still in their stone corrals began to chime, and wisps of smoke rose like soft incense from the thatched houses.

As I was gazing toward the river, I began to notice a familiar tugging sensation in my body. I had learned to listen to this subtle nudge, if not to actually trust it over the years. It comes with a knowing. I knew there was a stone out there in front of me somewhere near the edge of the river and that it was for me. Following this sensation, I wandered tentatively over toward the river, not wanting to expect too much. But there it was. I knew right away: this is the one. It fit easily into my hand. It was roughly in the shape of a trefoil, and on closer examination, looked a bit like a bird. It had that certain feeling I had come to know from the years on my shore. It was for me. I hadn’t asked for it. It called to me.

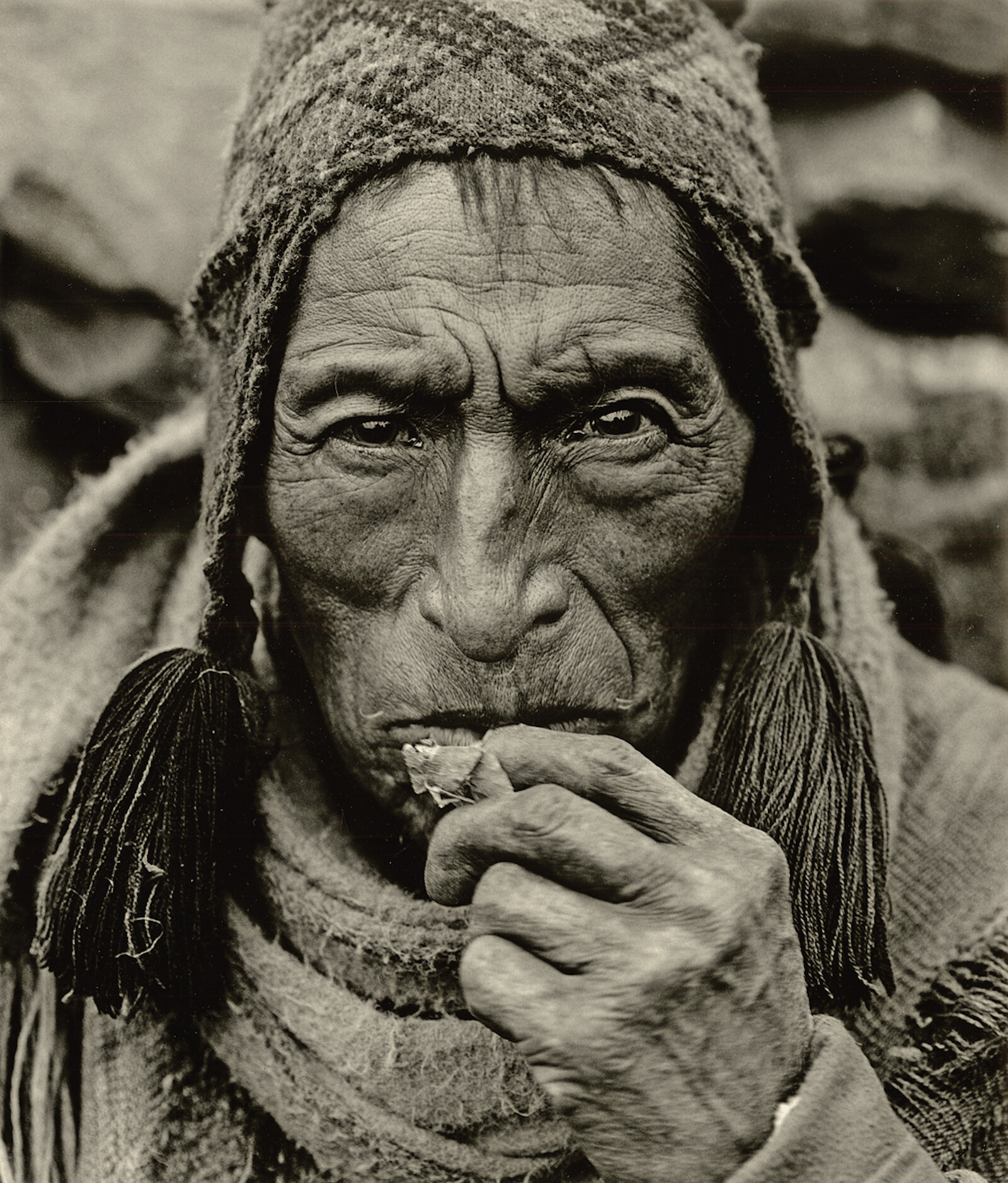

We were to meet with the three elder shamans (paqos) of the village after breakfast, and if the opportunity arose, I wanted to ask them about the stone. After the traditional cup of hot sweetened coca tea, we gathered in one of the rough stone houses that had been cleared out for our visit. Fresh straw was generously spread on the cold hard earthen floor. The three shamans sat close together in their traditional ponchos against a wall of rough-cut stones. We found our places. Their etched faces, the stone wall behind, and their woven ponchos crystallized a vision of ancestral strength born of centuries of faithful communion with the spirit of their land. They were humble and gracious.

They were joined by Puma, our young translator from a village near Cusco. He was a fresh faced eighteen-year-old, fluent in Quechua, Spanish, and English who radiated his own remarkable presence. When there was a break in our meeting, I asked Puma if they would look at my stone. I handed it over and the three of them eagerly crowded together to comment on it, enthusiastically pointing out telling features, each having their turn until they finally seemed to concur. The head shaman, Don Juan Pauqar Espinosa, looked up and Puma began translating.

“Yes, it’s a very good khuya. It’s a condor stone in a triangular shape and so it’s very good for distributing energy.”

“Oh, wonderful,” I said. “But… how do I work with it?”

“Well you open your mesa; you move all of your other stones to the outside edges and you put this one in the center. Then you bring the other stones around it. This one’s very good for distributing the energies.”

“Oh, thank you so much, Don Juan,” I paused. “But how do I work with it?”

He patiently explained again with more emphasis. Actually, I asked two more times, three times in all with emphasis of my own. “But how do I work with it?” Then came the moment I didn’t know I was waiting for. He held the stone in the palm of his hand, and as he leaned toward me our eyes met. Pointing his crooked finger to the stone, he said with a measured finality, “You believe in it without doubt.” My mind stopped. Or opened. It was as if I he had spoken a koan or a haiku. Something inside me fell away, some inner struggle suddenly released.

Working with Stones

The Q’ero mesa is a small, portable, personal altar. Primarily it is composed of stones, meteorites, or crystals wrapped in a traditional weaving. The stones may come from powerful mountains, rivers, lagoons, or other sacred sites important to the mesa carrier. Other stones or sacred objects may be gifts from one’s teachers or passed down from ancestors. The weavings are made by women of Q’ero villages to carry babies and young children. Eventually, after having been blessed with the energies of new life, they are passed on to the paqos. The sacred practices of the Peruvian Andes are Earth-honoring traditions. While they strive to live in harmony with the always fluid rhythms of our living cosmos, above all they honor Pachamama, Mother Earth. I have often heard them say, “we are sitting in the lap of Pachamama.” She births and nurtures us all.

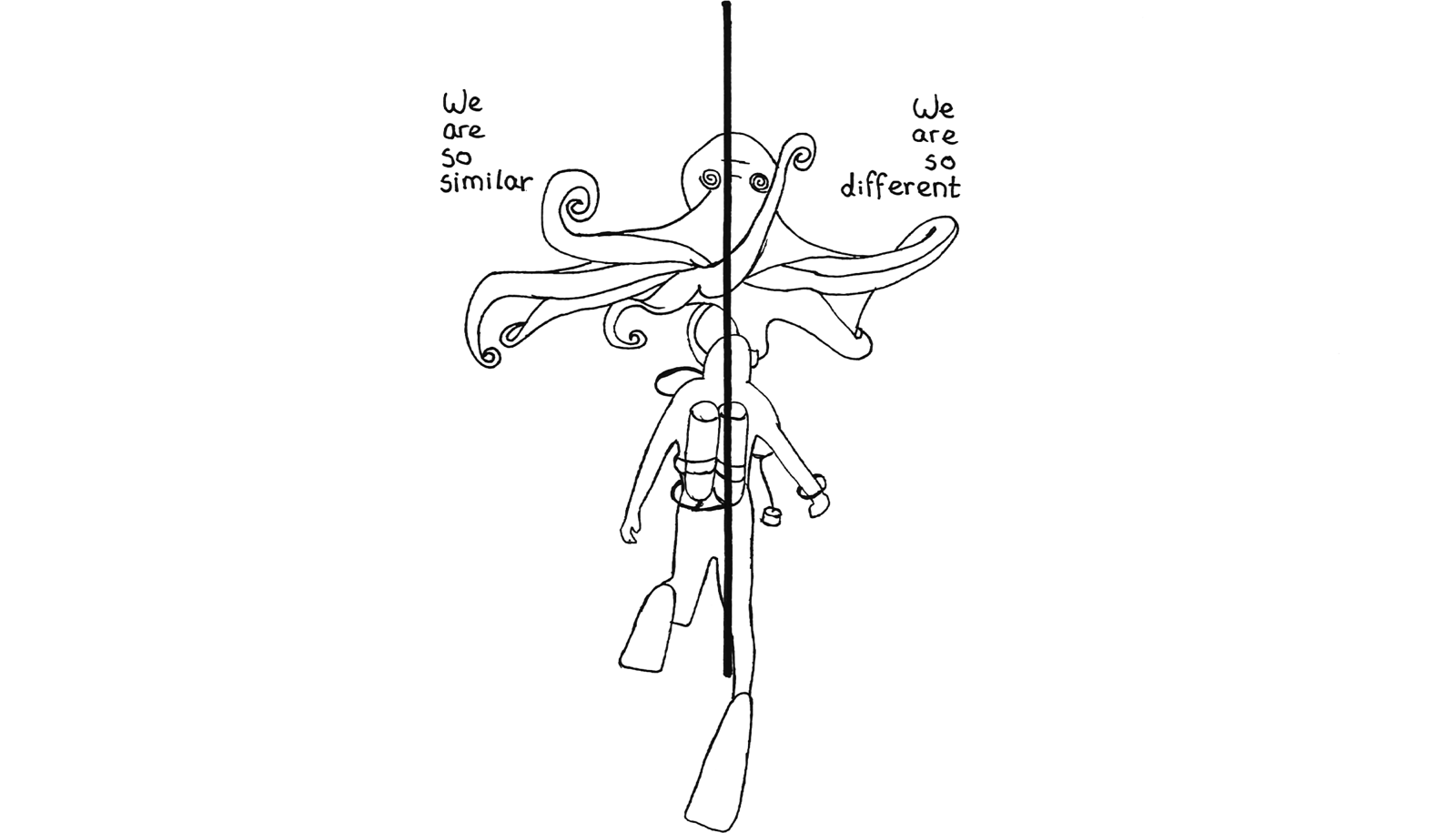

Stones in the mesa are called khuyas, which comes from a Quechua verb meaning “to care for deeply.” This heartfelt connection, nurtured over time, opens portals to the living cosmos all around us. With the aid of these stones, and the ritual practices that are part of the tradition, the paqo cultivates a profound relationship with places and beings of power and wisdom. A paqo’s power is not so much “held within” as woven on the loom of relationships they have patiently nurtured over time. These relationships can then be brought into service to help their family, their community, and the world. It is a path of service and its symbol is the llama. Without the selfless aid of the llamas, life at these high altitudes would not be possible. Llamas are celebrated and sung to in special festivals during the year. Every aspect of culture weaves the web of ayni, a sacred reciprocal relationship between all beings.

Don Sebastian Pauqar, the son of one of the paqos I met on my first trip, is a Q’ero master and good friend. We have traveled to sacred sites in the Andes together for years. Apu Ausangate is considered by the Q’ero as the most important mountain in the Cusco region. One day on the slopes of Ausangate at 14,000 feet, he instructed me to wander out to find two stones: one black one for the Pachamama, and one white one for the apu, the spirit of a mountain. “You are receiving a special strength from the apu. The stones are in our hands, but what we are having a communion with is not the stones but the force that comes through them from the apu. Do not doubt, do not hesitate. If it chooses you, it is coming with you! The stones will give you immense power and strength for your path and for your life. And remember you must kiss the ground three times, putting your fingers to your lips and then to the ground three times for each stone.”

Every stone shares in the essence of the place it comes from. They can be thought of as part of the family or tribe originating in that place. Our khuyas can be thought of as small holograms of the land or a living fractal of the whole.2 Just as the stone, the khuya, is an “energetic fractal” of the mountain or sacred place, the mesa is a microcosm of the paqo’s world. Their personal altar is their embodied communion with the places of power most important to them in both seen and unseen dimensions.

Once understood, these principles are extremely adaptable and applicable. The natural world is teeming with living vital forces that can be worked with intentionally to support the vitality of a person, a community, fertile fields, sacred sites, and more. The Quechua word “munay” brings together the idea of love and will linked together. The subtle fields of living energy which pervade creation, once connected, can be directed by our focused intent. With training, these “rivers of light” can be used to heal and rebalance people, places, and living systems. As Carolyn Dean writes:

Essence, as the Inka understood it, was clearly transubstantial. and rock was a special medium of embodiment … indigenous Andeans could transfer the essence (the kamay) of their waka to new locations in the following manner: if the waka was a rock or a hill, they could take an actual piece of the original and, by placing the piece (a material metonym of the original) on a new rock, transform the new rock into an embodiment of the original.3

The world is porous and responsive to consciousness. This is fundamental to a paqo’s awareness. The Inca used exactly these principles to “nest” Machu Picchu in a web of powerful living energies, by linking sites in the city to powerful mountains spirits in the surrounding landscape. Far from being separate from the “material” world, we are constantly exchanging energies with it. We have a choice to do it passively or actively, consciously or unconsciously. This is not news. Quantum physics has been stalking the sacred lands of mystics and shamans ever since they began investigating the shimmering twilight worlds of consciousness and matter a hundred years ago.

Looking Back

It has been twenty-three years since my first trip to Peru. At the time, I thought it would be a one-off trip to meet with the lineage of an authentic ancient tradition and to touch the earth from which it was birthed. I wanted to meet with elders who had come of age before being touched by the distortions of our Western worldview. To date I have returned more than thirty-five times. In one sense, it feels like a long remembering. Puma Quispe Singona, the eighteen-year-old translator became what I intuited he would become during our first meeting in Q’eros: the future face of his inherited tradition. Puma today travels internationally sharing his wisdom and transmitting the teachings of Pachamama. He is a major force for reinvigorating these traditional ways of knowing in his village and far beyond.

In the years following that first pilgrimage, I became part of Puma’s extended family and began learning all I could. In a classic sign of initiation, Puma had been struck by lightning at the age of six. After nursing him back to health, his grandfather, Don Maximo Singona Pumayalli, began secretly passing on his lineage to his grandson until his passing in 2008. I am godfather to Roderigo, Puma’s firstborn son, and we have become lifelong friends. Though I did not go to Peru to photograph, after all these years, I find myself with an extensive archive of images, many of which record a time that was beginning to pass even as I arrived.

These teachings, these ways of knowing are vital threads in the precious world-wide weaving of wisdom and knowledge that the ancestors of humanity have committed themselves to for countless generations. Many have written extensively about these realities in their own cultures, languages, and traditions. Plato called this unseen benevolent life force, this all-pervading consciousness that invites our intimate communion, the anima mundi, the world soul.

The greatest difficulty in accepting these earth-honoring mystical traditions has been my own Western enculturation: my disbelief, my doubts, my obsessive rationality, the timid limits of my imagination. I had no idea the challenge it would be to fully embrace the true depths of the teachings being revealed to me, teachings that have come from human mentors and directly from the whispering lips of Creation Herself. I had to overcome not only my own habits of mind, but the skeptical mind of the culture that lives within me and thinks my thoughts.4

And yet, these ways of being are profoundly who we are and part of our everyday congress with the world. Our bodies, our senses, our consciousness, and our imaginations are gifts from the gods.5 But their true power is obscured by Western culture’s official and aggressively enforced “acceptable” description of the world. We have mono-cultured our minds and disavowed the perceptual states all of our ancestors honored, cultivated, and trusted. Dream states, trance states, hypnagogic reverie, day dreaming, intense fasting, prayer, prolonged silent retreats in nature, ingestion of sacred plants, and more have been trusted paths to deepening our relationship with the wisdom inherent in every moment of creation. There is a heartbeat of meaning and relationship reaching out to us just beyond our over-busy distracted minds. The “doors of perception” are not closed; we have just been convinced there is nothing behind them. But our souls know and are naturally drawn to these depths wherever we can find them.

While our culture has largely lost the language that would allow us to usefully articulate our inherent abilities, we do have a rich Western tradition to look to. The imagination, while often dismissed as “fantasy” is, when regularly exercised, a reliable perceptual mode that dissolves the apparent barriers of separation we normally accept. This is how Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Blake, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge used their imaginations. George Washington Carver made his discoveries from talking to the plants and flowers in his forest. It is how Albert Einstein made his breakthrough while riding in a trolley car in Bern gazing at the clock tower. His was no “thought experiment”: he trusted his imagination to drink directly from the nectar of ancient starlight that pours into our world. Richard Wagner described how, in 1853 while lying in bed, he suddenly found himself at the bottom of the Rhine, water flowing over him as a “figuration” of music. It was a dramatic turning point in his life as a composer. Each of us responds to the touch of the living world according to our predilections. As Rabindranath Tagore, the famous Indian writer and Nobel Prize winner, wrote: “The more powerful the imagination, the less imaginary the results.”

While surely the creator of many wonders and benefits, the modern West has led us into a cul-de-sac of over-intellectualized materialist delusions. Our humanity, our imaginations, have been shrunk to fit into the “provable,” “repeatable,” “quantifiable” lab test of what sadly passes for truth. This is both tragic and unnecessary. What Don Sebastian offered me on that day in Ausangate was not answers but something far more profound. Through the stone, he was opening a portal of connection only you can make to the ever-present living mystery of creation that is older than humanity itself. We were always made for this. When we step past our enculturated doubt, we are able open to the world of awe, beauty, wisdom, and joy we easily accessed as children. Play, curiosity, and vulnerability are part of the practice. The all-pervasive intelligent fabric of the world responds to our deep intentional communion. It manifests as ideas, noetic knowings, epiphanies, synchronicities and a sense of being at home in the world. As we reanimate the world, we reanimate ourselves. This innate faculty of direct knowing is what modernity has specifically and methodically disavowed. Acquired “sophistication” obstructs our path to participating fully in the mysterious journey that is our life. When we find the courage to trust that knowing part of ourselves again, this ancient, wondrous world will open to share its gifts with us. As Puma would say: ”Nothing is yours, but everything is for you.”

For more information about the author’s works, see Carl Austin Hyatt Photography, ➝.

Hillary S. Webb, Yanantin and Masintin in the Andean World: Complementary Dualism in Modern Peru (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012), 134.

Carolyn J. Dean, A Culture of Stone: Inka Perspectives on Rock (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 62.

Amba J. Sepie, “Listening to the Elders: Earth Consciousness and Ecology,” in Greening the Paranormal: Exploring the Ecology of Extraordinary Experience, ed. Jack Hunter (Guildford: White Crow Books, 2019), 59–70.

Peter Kingsley, Reality (Inverness: The Golden Sufi Center, 2003).

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.

Category

Subject

As the article was being prepared for publication, the author received very sad news of the passing of Don Aogustin from Covid-19 last month.

This article is dedicated to the inspired souls whose commitment to preserving and cultivating the ancient Earth-honoring traditions have bequeathed us an immeasurably precious gift. From their seeds of wisdom nurtured over eons, we can re-member the sanctity of our world which even now blesses and sustains our every breath.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.